The 2003 film, House of Sand and Fog, depicts a tragic string of events that follows a woman who loses her house after ignoring eviction notices mistakenly sent to her for nonpayment of county taxes. She’s overwhelmed by the deluge of bureaucratic housekeeping demanded by contemporary American society.

I think of that beleaguered woman’s character whenever I receive yet another notice from my credit card company that they are changing their terms and conditions; when an airline urges me to join their frequent flyer program; when a client informs me that they never received the email I’m sure I sent.

Never is this deluge more front and center than during the immediate aftermath of the latest mass hacking, typically, allegedly, by online gangs in the former Soviet Union. During the Cold War, they said they would bury us. Now they are — in security-focused inanity.

In the latest fiasco, which has to make one question if we are really better off now than we were in the old days of passbook savings, they’re saying that as many as 76 million households may have had their account information compromised by an incursion into computers at the banking conglomerate JPMorgan Chase. “The intrusion compromised the names, addresses, phone numbers and emails of those households, and can basically affect anyone — customers past and present — who logged onto any of Chase and JPMorgan’s websites or apps,” reports The New York Times. “That might include those who get access to their checking and other bank accounts online or someone who checks their credit card points over the web. Seven million small businesses also were affected.”

We are supposed to be very, very scared. They want us to act. The banks and corporations want us to spend an awful lot of time and energy protecting their money.

Bear in mind, when someone steals your credit card data and makes unauthorized purchases or withdrawals, you’re not responsible. In short, it’s not your problem. But the media is colluding with the megabanks in order to make us care about something that we really shouldn’t.

Consider, for example, this advice to us banking customers in the Times article: “Those who want to add a layer of security to their financial life should consider a ‘security freeze.’ … When you freeze your reports, the big three credit bureaus will not release your credit reports to any company that does not already have a relationship with you.”

The paper continues: “Consumers need to approach each of the three credit bureaus — Equifax, Experian and TransUnion — and may need to pay a small fee, depending on where they live. The process can be a hassle because the freeze has to be ‘thawed,’ or lifted, to apply for a new credit card, for instance, or for a mortgage. (And consumers may need to keep PINs and other information handy to do that).”

Uh-huh.

So let me get this straight. Credit agencies that earn billions of dollars selling our information, much of it erroneous, want to charge us for our own data, so we can protect the big banks that we bailed out in 2009 at taxpayer expense and even now refuse to refinance mortgages or lend to small businesses, a major reason that the economy is still terrible, and waste God knows how many hours online or on the phone dealing with this boring crap.

Well, hear this, Russian hackers and American banksters: I’m a busy person. I have a lot to do. I work three jobs. If I ever find myself with any spare time, it’s going to be on the beach and involve margaritas and good books.

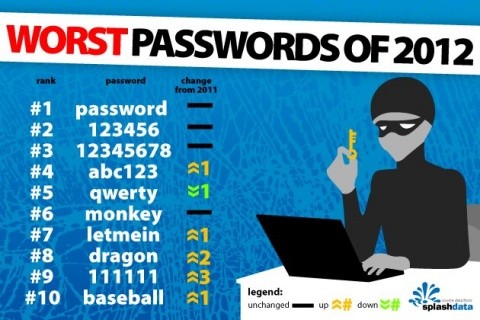

I am not going to change my passwords every time I read one of these security-scare stories. I refuse to pick new unique passwords for each of my dozens of accounts. I will not freak out on behalf of people who don’t give a damn about me or anyone I care about. And it will be a cold day in hell before I put a credit freeze on my own account and pay for the privilege.

Ted Rall’s next book is After We Kill You, We Will Welcome You Back As Honored Guests: Unembedded in Afghanistan.