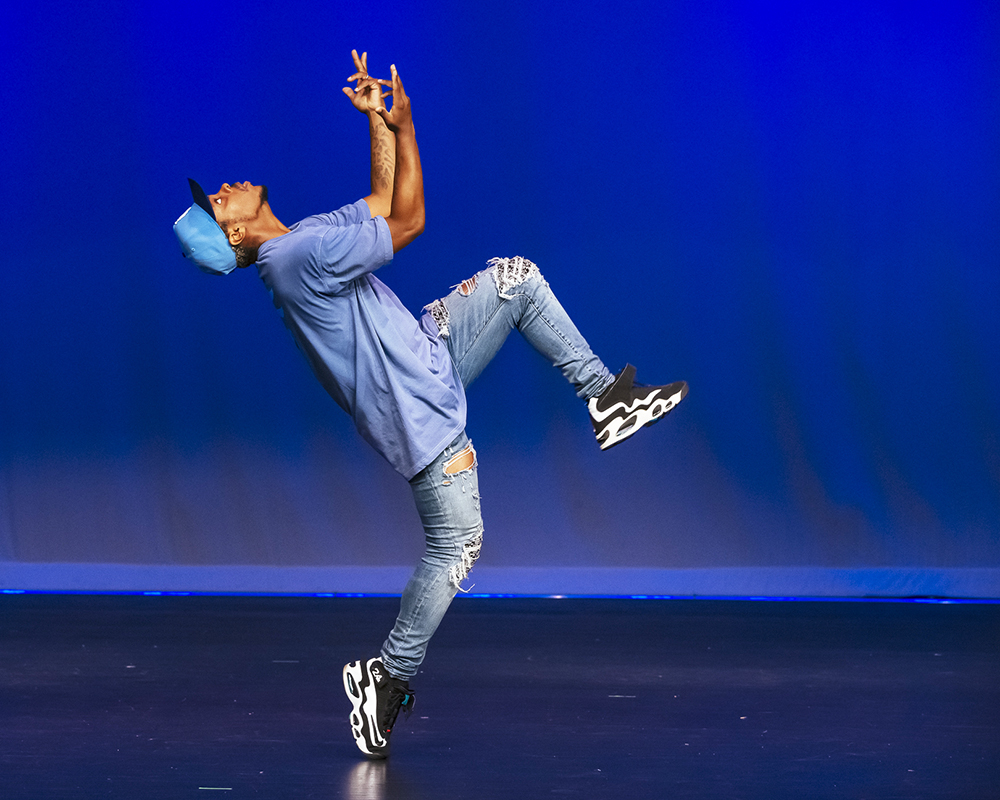

New York Times dance critic Alastair Macaulay came to Memphis earlier this year to learn more about jookin, a home-grown dance style he went on to describe as, “a virtuoso hip-hop descendant of the Gangsta Walk,” and “the single most exciting young dance genre of our day, featuring, in particular, the most sensationally diverse use of footwork.”

Though Memphis has produced a number of extraordinary jookers, none is better known than Charles “Lil Buck” Riley, who’s coming home this week to perform in New Ballet Ensemble’s (NBE) annual holiday show, Nut Remix.

Courtesy of New Ballet Ensemble & School

Courtesy of New Ballet Ensemble & School

Riley, who trained for a time with NBE, appeared in Memphis dance historian Young Jai’s video documentary Memphis Jookin: Vol. I. He first achieved notoriety when filmmaker Spike Jonze posted a cell phone video of Buck performing Camille Saint-Saëns’ The Swan, accompanied by celebrated cellist Yo-Yo Ma. Buck has since starred in a series of Gap commercials, danced with Madonna, and performed with the New York City Ballet and Cirque du Soleil. In 2012, he was listed as one of Dance Magazine‘s “25 to Watch,” and he has more than lived up to the prediction. As it happens, he’s also a great interviewee.

Courtesy of New Ballet Ensemble & School

Courtesy of New Ballet Ensemble & School

Memphis Flyer: You’re a really fantastic ambassador for Memphis. Everywhere you go you make us look good.

Charles “Lil Buck” Riley: I love it. And I love the city. It made me who I am now. And I’ve learned so much from living in Memphis. We do have so much to offer. And jookin is only one of those things. It came out of the gangsta walk, and that’s been around since the 1980s. My mom used to do it. So it’s more than just a dance, we’ve made it into a tradition. And I love being an ambassador for the style because I understand it wholeheartedly.

You’re only 26 and have achieved a level of pop star success most dancers never know. How are you still so grounded?

It’s easy to be. I think it’s harder not to be grounded. It’s really simple to be grounded and stay humble. Some people try not to be. Some people gravitate toward that, and you see a lot of that in the industry. But — and this is something I don’t think I’ve ever talked about — I was born in Chicago and raised in Memphis. I moved to Memphis at a very young age. And I’ve been through so much in my life. I grew up with nothing. And I lived with my mom and my whole family in my grandmama’s basement. It’s all we could afford.

When you come from things like this, and you have so much perspective as to how your life has changed and turned around for the better, you want to do everything you can to uphold that. Because it’s more than just my skills that have gotten me to where I’m at now. It’s who I am as a person.

And, like you always say, jookers take their power from the earth.

Well, you know, it is a really spiritual dance. It was something born here. Kids grow up into it. We use our feet and it’s predominantly freestyle, so it comes from the soul. You spend time with just you and your body, you know? You learn a lot about yourself with this style.

Jookin isn’t just a Memphis thing anymore, it’s all over the world. But it’s still growing here with jookin studios and companies, and folks meeting in parking lots and barber shops learning the original gangsta walk. Do you keep up with what’s happening at home?

Absolutely. I already know what you’re getting at. I’m coming back to Memphis and whenever I come home, we have exhibition battles just for the fun of it. And I’ll get in and dance with anybody. I go to people’s houses and we have sessions in the garage. Those are my favorite moments, and those are the things I miss about Memphis. I miss my family the most. But then I miss the old way we used to do things. Sometimes I just can’t wait to get back home and in the garage with my friends where we can just go at it like we used to, and dance.

When you see your old friends after dancing with Madonna, is it weird?

I’m the same Lil Buck that left. They love it when I come back because they know how much I love Memphis and how much I love jookin. People don’t get star struck because they know where I’m from. They knew me before, and I still don’t consider myself a star. I’m just getting appreciated for doing what I love.

But you are kind of a star. We have lots of movie stars and rock stars. But pop culture only taps a few dancers every generation and you get to be one of them.

Exactly. That was my goal. Dancers used to be seen on the same platform as actors. Especially triple threats like Gene Kelly and Fred Astaire. They looked good. They dressed nice. They had a passion for what they were doing and went full out 100 percent. I want to bring that back. That level of respect.

It doesn’t seem to matter if you’re street performing or on TV in front of millions, you exude comfort and confidence.

Everybody puts on their pants the same way. And street performing helped get me to that point. When I first started street performing, it was on Beale Street. When you’re street performing, you really have to develop your communication skills and learn how to be a people person. When I first moved to California, I performed in Santa Monica on the Third Street Promenade. And you’d get so many people down there and so many celebrities. If I noticed a celebrity was watching us, I’d make a joke. Everybody would laugh and they’d laugh too. And you get comfortable.

You’ve taught a lot of celebrities how to gangsta walk, from Madonna to Meryl Streep and Katie Couric. Who gets it and who needs to go home?

First of all, Stephen Colbert, he’s money. He absolutely should learn. He caught on to the buck jump so fast it was ridiculous. When you’re doing a buck jump it’s knee up, not foot down. A lot of people don’t get that. It used to frustrate the hell out of me. But Stephen Colbert caught on, and he looked good doing it. So he could do it for sure. Katie Couric? She would need a lot of work, especially if she wants to keep her heels on. But I love her to death. She did all right for a first time.

Who are some of your biggest Memphis influences?

I never really get to share about the people who really started me off and got me to this level and who gave me information that has stuck with me throughout my life and career. You know they call Marico Flake “Dr. Rico” for a reason: He’s a doctor of dance. He doesn’t just know about jookin; he’s a renaissance man who knows about a little bit of everything, from ballet to country dancing. Daniel Price is one of my biggest influences. When I sucked, he’d say, “All I can say, it don’t look gangsta enough.” And that would kill me.

Keviorr, aka “Tip Toe,” also kept it real. We used to be rivals. He was already known as an explosive jooker, because he’d been around all the old-school guys and had a reputation. I battled him at the Crystal Palace, not knowing who he was, because he used to go to East End Skating rink. I was the man in Crystal Palace, which was closer to Westwood. When me and him finally battled, everybody was around. And Keviorr was kicking my butt.

He said, “You’re good. I’m not going to talk bad about you. But you’re just going too fast. Your waves are too fast and people can’t see what you’re doing. You’ve got to slow down a little, that’s all.”

To hear that from the underground master of jookin? Man! Because he was like a ninja: Battle hungry and battle ready. If he said you were good, you were good.

Courtesy of New Ballet Ensemble & School

Courtesy of New Ballet Ensemble & School

2008 production of Springloaded

And now you’re a citizen of the world, dancing your way around the world. But you still take time to come back and perform with New Ballet Ensemble.

Of course. Why wouldn’t I? That’s as simple as I can put it. That’s my home. I love living everywhere. It’s always fun to meet people and learn new cultures. But I love coming home. There’s beautiful and negative stuff all over the world. And in Memphis there is more beauty and negativity. It’s just the way it’s been advertised and the way we look

at ourselves.

That attitude makes what you do really important, you know?

I am very aware of it. I know that with this great power I have comes great responsibility. It’s true. Corny as it sounds, it’s one of the realest lines I’ve ever heard.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

NBE founder and CEO Katie Smythe with dancers

New Ballet Ensemble

Great Power. Great Responsibility. Great Dance.

Katie Smythe doesn’t know when she’ll retire, but the founder and CEO of Memphis’ New Ballet Ensemble (NBE) is looking ahead and fantasizing a little, imagining what her life might be like in the future, when she finally passes the baton to a new leader, preferably a former student who knows the school and understands the mission.

“Maybe I could call myself the Chief Creative Officer,” she says, smiling, trying on one of several new titles she might assume when she’s no longer running the show. “I could be that.”

Smythe has every reason to contemplate a happy future — 2014 has been an especially affirming year for her and for all the dancers, teachers, and students at NBE, a 13-year-old professional dance company and school that helped to launch the spectacular career of jookin ambassador Charles Riley, known to dance fans around the world as Lil Buck.

“In the beginning, I think everybody thought I’d lost my mind, even my husband,” Smythe says, recalling early responses to her business pitch. In 2001, the lifelong dancer and sometimes soap opera actress wanted nothing more than to create professional dance opportunities in Memphis, and to train as many students as possible, regardless of their ability to pay.

Smythe had a specific vision for the future, but even she couldn’t have predicted the impact that moves born in Memphis clubs, skating rinks, and parking lots could have when they were blended with traditional ballet and the various other international dance styles that would find a home at NBE.

“New Ballet sees the value in the fusion,” Lil Buck says, remembering when Terran Gary’s Subculture Royalty Dance Company first started sharing space at NBE in 2005. At first, there wasn’t much crossover between the street dancers and Smythe’s ballet students, but that changed.

In April, NBE’s reputation earned the company an invitation to the Kennedy Center in Washington D.C. to perform original work commissioned for the National Symphony Orchestra’s “New Moves” mini-festival. NBE’s “Harlem” was choreographed by Smythe, set to music by Duke Ellington, and showcased the talents of NBE company member Shamar Rooks.

The Washington Post described the company’s performance as, “simply dazzling, eliciting an audience response that dwarfed all that had gone before.”

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

NBE dancer Briana Brown

This month, Smythe returned once again to the nation’s capital, this time with 17-year-old dancer and student Briana Brown in tow. Brown, who started training with NBE at age 7, represented her fellow students when the White House honored New Ballet’s educational branch, alongside 11 other life-changing after-school arts programs selected to receive the National Arts and Humanities Youth Program Award.

Brown, whose smile threatened to break her face as she accepted a hug from First Lady Michelle Obama, called NBE’s award, “A huge responsibility.”

NBE brings its landmark 2014 season to a close this weekend, when the company partners with the Memphis Symphony Orchestra for a very special revival of Nut Remix, the company’s locally bent but internationally flavored take on The Nutcracker. In addition to moving the company’s annual holiday show from GPAC to the Cannon Center, this year’s Remix also reunites two of NBE’s most successful alumni, Lil Buck and Maxx Reed, who spent five years web-slinging in red-and-blue tights, playing Spider-Man in the U2-scored Broadway musical, Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark.

Lil Buck’s unprecedented journey from relative obscurity, dancing at The Crystal Palace skating rink in South Memphis to dancing with Madonna at Superbowl XLVI, is well documented. But Reed’s quieter story is also indicative of the kind of work that happens at NBE, and his career path represents a more realistic trajectory for working dancers.

“Ms. Katie literally found me dancing on the street corner,” says Reed, who was 13 and performing at the Cooper-Young festival with other dancers from DeWayne Hambrick’s Graffiti Playground, a Midtown-based program that offered free performing arts training to young people.

“Ms. Katie asked if I’d like to dance with some ballerinas and I said, ‘Nope,'” Reed recalls. “That just didn’t sound fun to me at all.” Instead of giving up, Smythe offered to get tickets for Reed and his mother to see the Chicago-based Hubbard Street Dance Company at GPAC.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

NBE alum Maxx Reed

“It was amazing,” Reed says, recalling how the Hubbard Street performance awakened something in him. “I used to dance competitively, but it was expensive,” he explains. “And I quit after I heard my parents arguing about a credit card. I felt like I was too much of a burden or something.”

The Hubbard Street concert changed Reed’s mind about dancing with ballerinas. If Smythe could train him to dance like the men he’d seen and there was a chance that he could someday make money doing that, he was all in.

“Here were these incredible technical dancers,” Reed says of Hubbard Street. “These powerful men were doing all these jumps and turns. They were like bears moving through space and eating up space in this incredible display of power and beauty.” The teenaged street performer was especially impressed by the chair-jumps and spins of a dancer named Christopher Tierney.

“Here’s the crazy thing,” Reed says. “On my first day doing Spider-Man on Broadway, I went back to the dressing room to meet my castmates for the first time. It turns out I was sharing a dressing room with Chris Tierney, the same dancer that I remembered jumping up on that chair. The dancer who made me want to be like him. We shared a dressing room and both played Spider-Man for three years after that.

In addition to playing the world’s most popular superhero eight shows a week for five years running, Reed has appeared in numerous commercials and music videos. He was hand-picked by Michael Jackson to audition as a dancer for Jackson’s farewell tour, and although he didn’t make the final cut, Reed says it was an honor just to “share airspace” with the King of Pop. Not too shabby for a dyslexic, severely ADD kid who remembers an elementary school teacher telling his mother that her son would never develop the skills required to succeed in life.

Reed knows as well as anybody how difficult things can be for kids who are socialized to believe they can’t succeed. He was reminded this summer, when he returned to Memphis to teach a youth dance program at NBE. After introducing himself to a class of young students, and telling them about all the cool things he’s done, an incredulous little girl’s voice rang out from the back of the room: “But you’re from France,” she said.

Reed shook his head and assured his pint-sized heckler that he was every bit as Memphis as she was. He describes the summer class and his students’ self-choreographed performance as the highlight of his career. “I want to come back and do this every year,” he says.

Even if she’s not planning to retire soon,

Smythe has what she calls a dream scenario: “I’d love for Charles and Maxx to become my succession plan,” she says. “They could run the place, and I could graduate to chairman of the board. And I could teach ballet whenever they need me.”

Courtesy of New Ballet Ensemble & School

Courtesy of New Ballet Ensemble & School  Courtesy of New Ballet Ensemble & School

Courtesy of New Ballet Ensemble & School  Courtesy of New Ballet Ensemble & School

Courtesy of New Ballet Ensemble & School  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks