A leader of the group of lawmakers exploring whether Tennessee can feasibly reject nearly $1.9 billion in federal education funding says that the panel’s work will begin in early November, and that its findings — not politics — will guide its recommendations.

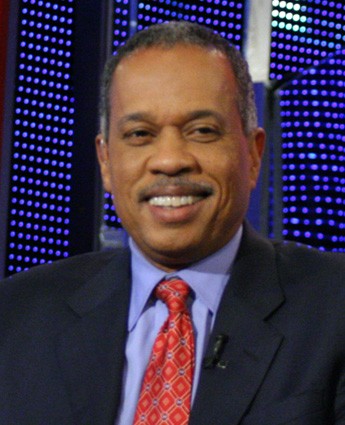

“There is no predetermined outcome for this working group, or for what the information we gather is going to show,” Sen. Jon Lundberg, a co-chair of the panel, said Wednesday.

“We want to look at what federal education money we get, where it goes, what we’re required to do to get those funds, and ultimately what’s the return on the investment,” the Bristol Republican told Chalkbeat. “I think this will give us a good overview.”

Lundberg, who also chairs the Senate Education Committee, was responding to criticism from Democrats that Republicans are seeking to undermine public education, cater to charter and private school interests, and advance the political aspirations of House Speaker Cameron Sexton, a Crossville Republican and likely candidate for governor in 2026.

In February, Sexton said Tennessee should consider forgoing U.S. education dollars to free schools from federal rules and regulations, and should make up the difference with state funding. On Sept. 22, he and Lt. Gov. Randy McNally, an Oak Ridge Republican, appointed eight Republicans and two Democrats to the working group to look into the idea and report back by Jan. 9, when the General Assembly convenes a new session.

Most of the federal money the state receives supports low-income students, English language learners, and students with disabilities. Tennessee school districts that are most reliant on U.S. dollars tend to be rural, and have more low-income and disabled students, less capacity for local revenue, and lower test scores in English language arts, according to a recent report from the Sycamore Institute, a nonpartisan think tank.

Lundberg expects to release the panel’s meeting schedule later this week. But at this point, its members have more questions than answers, including what such a shift in funding would mean for kids. If the January 9th deadline doesn’t allow for a comprehensive review, he and co-chair Debra Moody, who also chairs a House education committee, plan to ask for more time.

“This is too big an ask to not be thorough,” he said.

If the committee finds ways for the state to feasibly wean itself from federal education money that Tennesseans help generate through their taxes, Lundberg expects legislation to come out of its work. But he acknowledged that state revenue collections have lagged in recent months, potentially making it harder to cut the cord.

“Revenues are a valid concern, but that’s not our charge at this point,” he said. “We just want to do a deep dive on where we stand.”

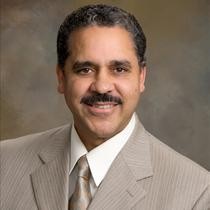

Senate Finance Committee Chairman Bo Watson warned lawmakers in August that Tennessee likely will need to begin curbing state spending. But on Wednesday, he endorsed the panel’s task.

“I think it’s premature to say whether there will be budget constraints,” said the Hixson Republican. “Evaluating our programs and our funding is always a healthy exercise.”

Even if officials decide the state can afford to pass on federal funds, JC Bowman, executive director of Professional Educators of Tennessee, questions whether it could effectively manage resources designed to support underserved communities and ensure equal access to education.

He cites the Achievement School District as one example of poor oversight for a state-run program intended to serve students attending low-performing schools. The turnaround district took over dozens of neighborhood schools beginning in 2012, mostly in Memphis, and turned many of them over to charter operators. But it has had few successes to show for its decade of work.

Lundberg said that example shouldn’t stop the state from investigating the possibility.

“Do I trust the state more than the federal government? Absolutely,” Lundberg said. “I think that government that operates closest to the people is the best government.”

Gov. Bill Lee has said he’s open to the idea and denounced what he called “excessive overreach” by the federal government. However, he didn’t give specific examples on education when answering questions from reporters last week.

Advocates for historically underserved student populations say federal oversight is needed to ensure that the state and local districts adequately provide for every student and school.

Meanwhile, Senate Democrats pointed out that the federal government provided nearly $30 million last year to public schools in Cumberland County, which Sexton represents. That’s 44 percent of the East Tennessee district’s budget. Three school districts in Anderson County, where McNally lives, received $31 million in U.S. funds, which covered 32 percent of their budgets.

You can look up exactly how much federal education funding is on the line for every Tennessee county.

Marta Aldrich is a senior correspondent and covers the statehouse for Chalkbeat Tennessee. Contact her at maldrich@chalkbeat.org.

Chalkbeat is a nonprofit news site covering educational change in public schools.

Greg Cravens

Greg Cravens