We Memphians know all about Sam Phillips and the legendary Sun Records, but who among us has heard of CZYZ Records? That might have been the name of the label that put Muddy Waters, Etta James, Howlin’ Wolf, Bo Diddley, Chuck Berry, and others on the map, had not the Polish-Jewish Czyz family followed the classic immigrant’s practice of Anglicizing their name at Ellis Island — to Chess. As a result, of course, Chess Records, founded by the brothers Leonard and Phil Chess in 1950, became as much a keystone of the blues and rock-and-roll tradition as Sun Records or any other imprint in the business.

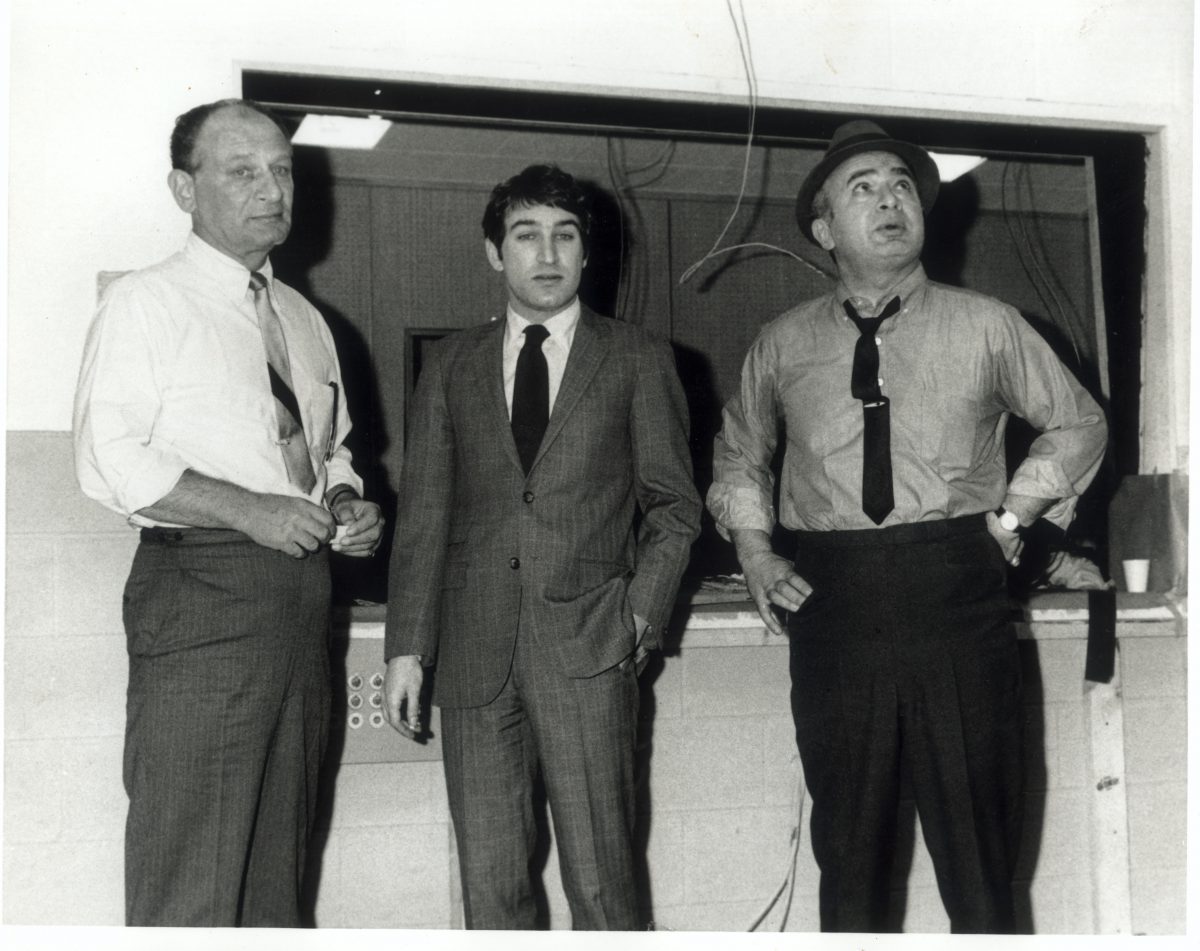

It’s worth noting the family’s old country surname because now, years after Chess Records was sold and became only an archival catalog, CZYZ Records really is a thing. That’s thanks to the ongoing efforts of Leonard’s son Marshall, who was in the thick of his father’s business from a young age, ultimately moving on after the legendary label was sold so he could head up Rolling Stones Records in the 1970s. These days, half a century later, he enjoys the quiet of the forest near Woodstock, New York.

“My daughter lives up the road,” he says contentedly. “And my son is right across the street. I have two grandchildren, and they come up all the time. So it’s like a little village.”

That’s where he dreams up projects, sitting in a small log outbuilding with a wood stove that serves as the ultimate man cave, stacked to the rafters with records (including God only knows how many first pressings), tapes, CDs, books, and the odd guitar. In the back is his floatation tank, not unlike those featured by Memphis’ own Shangri-La Records in its early days, and perhaps that explains his very active mind and clear-eyed memories. He’ll pivot from tales of recording Maurice White one minute, to his days crashing at Keith Richards’ house the next.

These days, he’s more often telling stories about the making of CZYZ Records’ newest album, New Moves by The Chess Project. Fittingly, it’s a tribute to the label his father and uncle launched, but done in an innovative way. Rather than using players from the blues world, Chess enlisted Keith LeBlanc, an old friend of his who got his start at the legendary Sugar Hill Records, drumming on classic tracks by Grandmaster Flash and Melle Mel. LeBlanc, in turn, assembled a crack band that included Memphis virtuosos Eric Gale on guitar and MonoNeon on bass, along with Skip “Little Axe” McDonald (Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five); Paul Nowinski (Keith Richards, Patti Smith) also on bass; Reggie Griffin (Kenny “Babyface” Edmonds, Chaka Khan) on keys; Alan Glen (Jeff Beck, Peter Green) on harmonica; and Mohini Dey, an up-and-coming young bass player from India. And then they added the ringer: someone who could deliver the classic songs from the Chess Records catalog.

“We had a bunch of ideas for vocalists,” Chess recalls. “And then we came up with Bernard Fowler. He’s a great vocalist. I mean, just listen to his work in Living Colour!” Fowler worked on that band’s 1993 album, Stain, but he’s even better known for being the Rolling Stones’ go-to backup singer since 1989.

The resulting album, though centered on classic tracks hand-picked by Chess himself (including “Boom Boom (Out Go the Lights),” “Moanin’ at Midnight,” “Mother Earth,” and “Smokestack Lightning,” to name a few), is not a traditional blues album at all. Rather, Fowler reinterprets the songs with his distinctively bold delivery, with the crack band backing him in a free-form funk style. Given the funky underpinnings of the record, it’s no surprise that the thing Marshall Chess loved most about it was LeBlanc’s playing.

“I called up Keith and said, ‘You know, my dad would have kissed your ass! Your foot is just the kind of foot he wanted in the blues.’” He began telling LeBlanc of Leonard Chess’ habit of playing kick drum himself on certain tracks, to ensure a heavy beat (c.f. Muddy Waters’ “Still a Fool”). LeBlanc, Chess said, had that same heavy-footed approach to the kick drum. But LeBlanc interrupted him. “Keith said, ‘Wait a minute. Stop.’ I said, ‘Why?’ He said, ‘That’s not my style foot. I copied all those records you gave me!’ That was my dad’s style [of playing the kick] that I was hearing, through Keith!”