Courtesy Christopher Reyes

Courtesy Christopher Reyes

Omar Higgins plays the Food Not Bombs benefit show in 2009.

Omar Higgins, 37, died on April 18th, 2019 from complications related to an untreated staph infection. The Memphis music community expressed shock and grief at the unexpected passing of the bassist and bandleader of Memphis’ premiere reggae band, Chinese Connection Dub Embassy (CCDE), and the buzzed-about hardcore outfit, Negro Terror — the man everyone knew as simply Omar.

“I’ve struggled to find the appropriate words to share with everyone about how much Omar meant to me,” says Kris Garver, DJ who has been friends with Omar since they were teenagers. “I don’t quite remember how I met Omar, in person. It might have been at Kirby High School, it may have been at the Hickory Ridge Mall or even on the front stoop at his house, a place that was Omar’s de facto headquarters for as long as I’ve known him. Our mutual friend kept talking about this friend of his, Omar, who was so fucking rad and knew how to play the bass and loved kung-fu movies and cartoons and knew about all kinds of fucking music, and just moved here from Brooklyn.”

Garver says he and Omar were “music nerds, amateur musicologists. We would talk about all the kinds of bands we wanted to form.”

Joseph Higgins, who along with his brother, David, formed the core of CCDE, says Omar was born in Memphis, but lived in Brooklyn for “a good chunk of his life. He loved it so much. That was the place where he honed his skills on punk rock. But he brought his skills back here to Memphis and we sharpened our swords like crazy.”

[pullquote-7] Omar Higgins was an Army veteran who served in the Iraq War. “He talked about it, but it was always something that he tried to keep to himself,” says Joseph Higgins. “He loved this country. Anybody ever try to talk bad about it, he would say, ‘nah, this is my home.’ We were born here. You black, white, Asian, whatever. We are all one….In Iraq, in the field, we’re all brothers, we’re all one. That’s the only way we get a chance to come home. We can’t be like, ‘I don’t protect this person, because he’s this, or I don’t protect this person, because she’s that.’ That was one thing he brought back: The whole mentality of, we are all one. He was just trying to be the best Omar he could be.”

The Higgins brothers played together in worship bands at churches such as IPC, New Beginnings. Miracle Redemption, and New Genesis. “They have done nothing but show us love and let us hone our skills,” says Joseph. “Omar talked about those churches as things that kept him centered. With all the wickedness and crazy stuff that went on the world, we all need that assurance, hope, and peace. We got that from reggae music, and the churches.”

Omar’s spiritual beliefs were as idiosyncratic as they were deeply felt. In John Rash’s award-winning 2018 documentary Negro Terror, Omar claimed a strong affiliation with Hari Krishna, and performed a blistering psych-rock chant in his name. He was a spiritual seeker, who found deep meaning in the healing and uniting power of music. “If you didn’t like him, you just don’t like good energy,” says rapper SvmDvde. “He never told anybody to harm this person because they were gay, or harm this person because they were white or black — except racists and rapists. Omar was an advocate for women. I feel like if he could catch a rapist, he would hang a rapist.”

While playing punk rock in Brooklyn, Omar became associated with Skinheads Against Racial Prejudice (SHARP), which arose from the first-wave ska scene in late 1960s London. The SHARPs, who appropriated the logo of Jamaican reggae label Trojan Records as their own, are a loose-knit, anti-fascist organization who acted as a counterweight to the violent, racist skinheads who infiltrated punk rock culture in the 1980s and 90s.

When he returned to Memphis in the mid-2000s, Omar dove deep into reggae history, and started training his brothers to play the music. “I was always into hip hop and R&B and a little bit of rock,” Joseph says. “Bob Marley was a great artist, but I thought he was the only one people listened to. Omar introduced me to Gregory Issacs, Barrington Levy…I fell in love with reggae.”

Omar Higgins had a well-earned reputation as a demanding bandleader. “Anybody that we have ever featured or had join us on stage, they had to do their homework,” says Joseph.

[pullquote-6] Singer Kween Jasira of Ras Empress, who frequently sang with CCDE, says, “Omar taught me to be knowledgeable about what you’re doing. Some people play certain music, and sing certain music, but they don’t understand it. They just sing it because it sounds good. Omar had knowledge about not only reggae and rock, he had a true love of music, regardless of genre. Not only true love, true knowledge…Omar really taught me to research my craft, and let that shape me as an artist.”

CCDE drummer Donnon Johnson says, “He was really a James Brown type. He was very specific about how music should be played. One rehearsal, when I first got into the band, I watched Omar literally change instruments, teach piano and guitar parts, give a horn line, voice lines, and show me what drum pattern to play, all in one rehearsal…Nine times out of 10, he was the most skilled musician in the room. But he was the least likely to try to show somebody up, or exhibit any type of attitude. He was the most skilled and the most humble on any stage he was on. That’s his legacy.”

David Higgins says the band passed up offers from a record label in 2009. The label executive “…loved what we were doing. He had never seen anyone like [Omar] who was an American.”

But the label wanted the band, then known as the Soul Enforcers, to stop playing club shows and record with them exclusively. “Omar would never sign on the dotted line,” says David. “He was like, I want to keep playing. This guy doesn’t want us to play out. So we’re going to keep doing it under the name Chinese Connection Rhythm Selection. I came up with the Dub Embassy part…The name is funny. It was supposed to be a thing so Omar could go out and play, to minister to people, to play life music. That’s what reggae music is, life music. We wanted to get out there and keep that camaraderie going. He didn’t want to record until he was ready, until we were all mentally ready. He didn’t want to take us through a whirlwind of BS. I’m glad we did it the way we did, the underground way, the independent way. That’s what everybody’s doing now. Nobody wants to be signed to some big label. Independent is where it’s at. Omar was ahead of his time.”

At first, Omar’s version of a ministry meant playing in some of Memphis’ worst dives. Negro Terror guitarist Rico Fields met Omar at the notorious Rally Point in the University of Memphis area. “The Buccaneer was the Cotton Club compared to the Rally Point,” Fields says. “That’s where you went when you couldn’t go anywhere else.”

[pullquote-5] An early supporter was Eso Tolson of the a cappella hip hop act Artistik Approach. His series of Artistik Lounge shows featuring up-and-coming artists started out at the Rumba Room in Downtown Memphis. Tolson booked Chinese Connection Dub Embassy to play. “His charisma, his stage presence, his energy was just so compelling…That’s when I knew these guys were special. It was a rainy Sunday night. The energy was living good. There were a lot of up-and-coming musicians there. Right after the performance, it was sprinkling outside. They were putting up equipment. Donnon, on the drums, he just had his snare, and he started playing this rhythm. He’s from New Orleans, it was like a second line. Then Suavo came out with his trombone. Omar and me were outside chanting in the rain with this second-line energy. They had just played this amazing set, and here we were, on the street in the rain, chanting. It was that energy they created, and that vibe they had. Omar was the leader. He had that spirit. People trusted him. They valued his wisdom, his ideas, and his leadership. Chinese Connection traveled all over the South and the Midwest, and people were catching those vibes. But that performance was a pinnacle for me.”

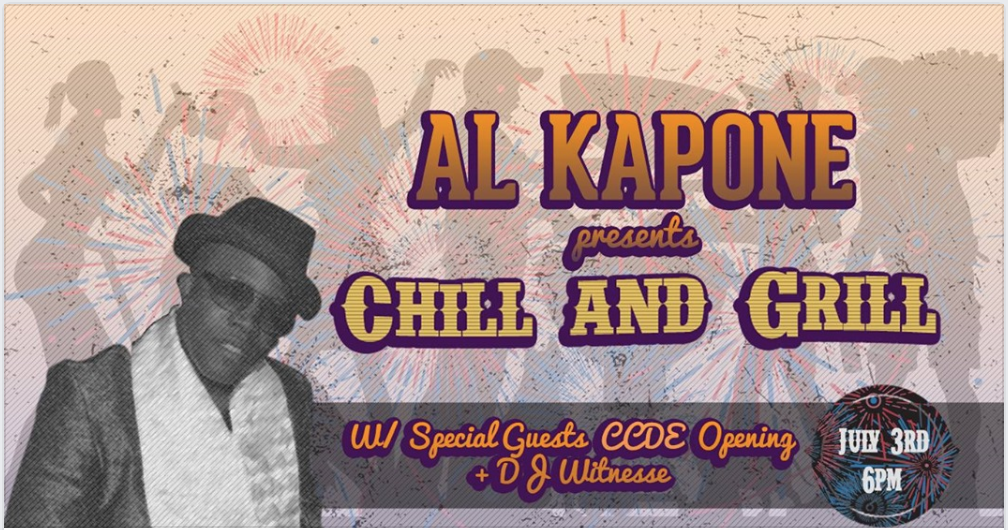

[pullquote-4] From that point on, CCDE was the house band. “The Artistik Lounge is kinda like a convergence,” says rapper PreauXX, who frequently performed with the band. “Omar had this powerful energy about him that commanded your attention, but it was so thoughtful, so grateful. It was, ‘don’t bullshit me, because I’m stylin’ in your face.’ It was an honest person. I love characters like that…They brought me to one of my first festivals, the Wakka Roots festival. I didn’t have any money to my name, and they said, ‘PreauXX, get in this truck and come tour with us.’…Any time performing with them, it was always a family reunion.”

“They are completely different,” says Kween Jasira, who also began playing with the band around the same time. “The other bands I had been with, there were singers, and there were musicians, if that makes sense. CCDE are a complete package. They are the definition of one band, one sound. You don’t just have singers with the musicians playing behind them, background singers to the side. The entire band is responsible for the sound, and for the singing. It’s a self-contained thing that I hadn’t seen before. But what makes them unique from other bands is they found a way to integrate themselves with other genres of music, and other artists. They found a way to bring hip hop and reggae together, and R&B and reggae together. The way they immersed themselves in the artist community around them, and both spread their seeds and became a part of what was already there, and bringing people into reggae as well. A lot of those people didn’t know reggae, or even knew that they liked it at the time. They’ve never given it a chance. But the way CCDE moved in the artist community, they were exposing that roots reggae, and people latched onto it.”

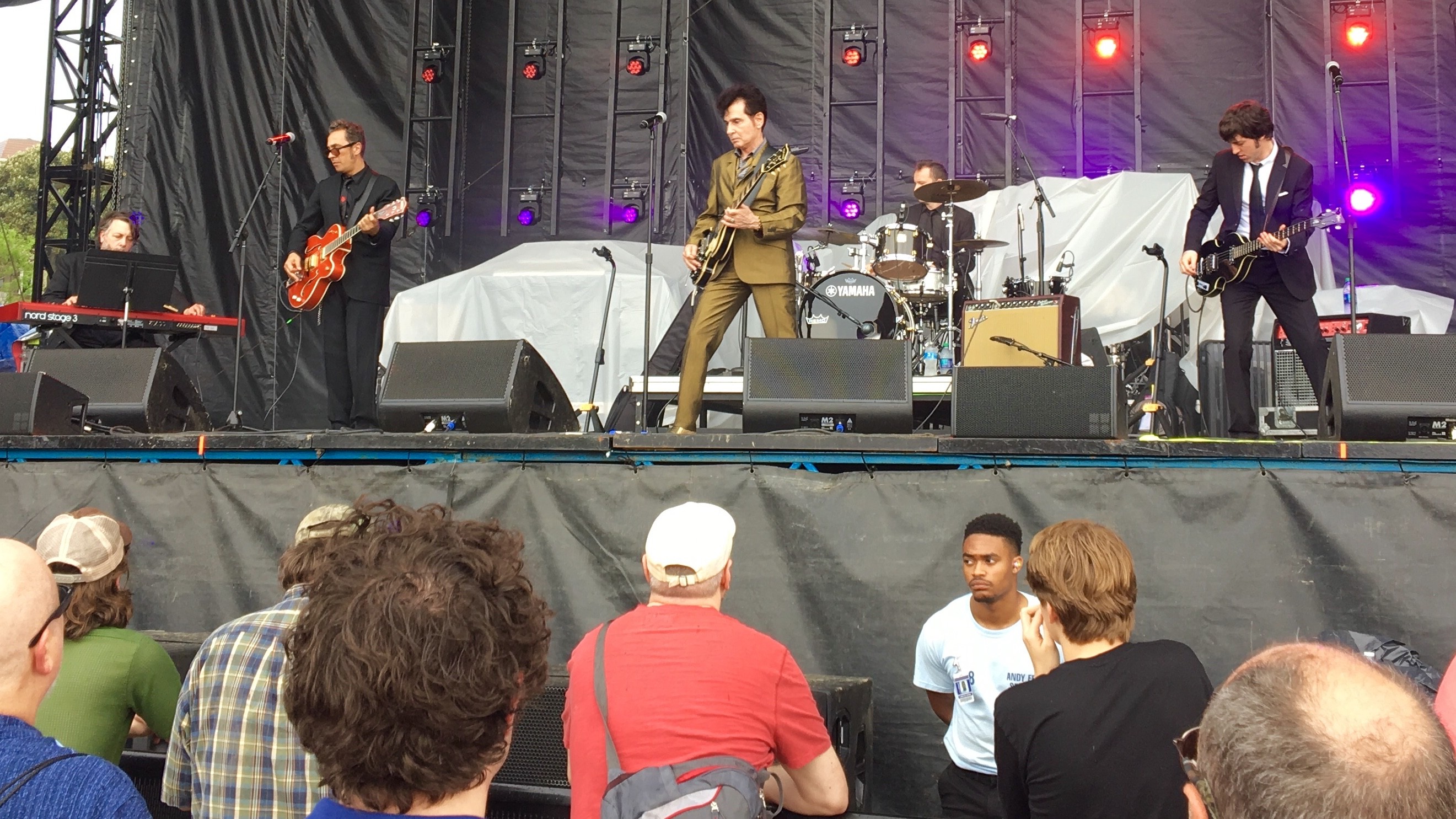

Chris McCoy

Chris McCoy

Chinese Connection Dub Embassy playing the 2018 Beale Street Music Festival

PreauXX says, “(Omar) could hang with the hipster kids, he could hang with the grunge kids, he could hang with people who love reggae music. He could move fluidly throughout all of these communities and be appreciated. It’s a rare feat. There will never be anyone else like that.”

“Musically, that is one of the tightest bands you’ll see,” says Justin Jaggers. “It’s just fun to watch them perform, and nonverbally communicate. A look from Omar, a response from Joseph, and they just know what to do.”

Jaggers is the organizer of Musicians for LeBonheur. In 2013, he reached out to CCDE. “The quickest ‘yes’ I got was from those guys….I was just blown away by their response. They would do anything we asked them to do.”

Jaggers arranged to have CCDE play for LeBonheur patients. “There was this kid who had some kidney issues. He was 19 or 20, and just a frail, small guy. We went into the room, and he just looked miserable. These guys started playing, and they were interacting so well with each other. The kid kinda lifts up his arm and starts dancing with the only body parts he could move. You know that kinda had to hurt a little bit, but he wanted so badly to be a part of this music.”

CCDE’s reputation and fan base grew with their 2013 album The Firm Foundation, named for an earlier incarnation of the group. But the ever-restless Omar continued to branch out. Omar sat in on bass with cowpunks Jocephus and the George Jonestown Massacre. “We had another underground project called the Cotton Pickers,” says David. “We used to work for Mr. [George] Klein for Elvis Radio. We had another project called Ten Foot Ganja Plants, and another called John Brown’s Body. We had a studio thing, and a live thing. We were going to drop this thing called Slave vs. Master. We intend to put that out in the future as a tribute to Omar.”

[pullquote-3] CCDE had a minor hit with their grooved-up cover of A-Ha’s synth-pop classic “Take On Me,” Joseph says, “That was Omar’s thing. For the longest, he wouldn’t do a Bob Marley song, because he didn’t want to be a cover band. But we were like, this is Memphis. People love Bob Marley. So he said, ‘OK, but if we’re gonna do it, we’re gonna do it Chinese Connection Dub Embassy way.’ Every time, if you heard a cover we did, it’s not like the original song. If we’re going to do this, we’re going to do it our way.”

I first met the Higgins brothers backstage at the David Bowie tribute concert at Minglewood Hall organized by Memphis musicians after the legend’s 2016 death. I had seen them play before, but up close, the 300-pound Omar’s energy was intense and unmistakable. Five months later, I watched them steal the show at the Prince tribute with Omar’s stunning arrangement of “How Come You Don’t Call Me?” The next time I saw them play at the Hi-Tone, Omar greeted me as soon as I walked in the door. Offhand, I asked if he knew “Heathen” by Bob Marley. The band then opened their set with a barn burning version of the song.

Omar was cooking up a fresh surprise. He recruited his old friend Rico Fields and drummer Ra’id to get back to his hardcore punk roots. “When he hit me up about the idea, all I knew was I wanted to be involved with it,” Fields says. “I didn’t know nothing about skinhead subculture, nothing. I knew enough about punk to have a conversation, but I wasn’t a sub-genre guy: American, oi, this punk, that punk, whatever. I was like, there’s more than one? He was an encyclopedia. He drilled us hard for a year. We didn’t do any shows. All we did was practice.”

Courtesy Christopher Reyes

Courtesy Christopher Reyes

Omar Higgins plays with Negro Terror at the 2019 Black Lodge Halloween Ritual

[pullquote-1] The band would become the controversial Negro Terror. “We knew to get the message out, it had to be crazy,” Fields says. “There were five or six other band names that came before Negro Terror. Some of them were like, you should never, ever say those two words together ever again. That’s going to get us arrested.”

Negro Terror’s mission was to challenge the assumption that punk is an exclusively white genre. “Growing up in the 80s, 90s, that’s what they told you: You’re black, so you have to be gospel, hip hop, or R&B. You gotta stay in your church. Folks like me and Omar, we love black music. If you could put a color on popular music in America, it would be black. I’m never one of those people who says certain colors need to stay in certain genres of music. And Omar was the same way.”

Negro Terror instantly made a big impression. “People were very confused at first,” says Fields. “They were used to seeing Omar play reggae, because that’s what he was known for…When we did our first show at the Hi Tone, we kinda decided to fuck with the crowd, and play reggae first. Then, all the sudden, I turn that distortion on, and people were just like, ‘whoah, shit. It’s about to go down.’ Then he started singing, and people were like, is that Omar’s twin brother? Who is that?”

[pullquote-2] One of Negro Terror’s earliest coups was a cover of “Invasion” by the infamous English racist band Skrewdriver. Fields says Omar was determined to do it better than the fascists. “Literally the only negative reactions we got were from racists. We even had a white supremacist on YouTube comment on ‘Invasion’ who actually showed respect. He said, ‘I may not agree with you ideologically, but you know what? You did really good on this song and I really like it.’ I’m the dude who handles the social media, and I was like, ‘Thank you? I think?’”

One of Negro Terror’s most notorious gigs was playing in front of City Hall during the protests surrounding the Madison Hotel’s (now Hu’s) forced eviction of artist and Live From Memphis founder Christopher Reyes from his home at 1 S. Main. “I didn’t know him all that well,” says Reyes. “However, he was part of the Live From Memphis scene, always doing something. What stands out in my mind mostly is how he supported my family in our time of need.”

Chris McCoy

Chris McCoy

Rico Fields performs with Negro Terror in front of Memphis City Hall during a protest in April, 2018.

Negro Terror was the subject of a documentary by Mississippi director John Rash. The film included incendiary performance footage and intimate interviews with the band members. In the film, Omar revealed that he had a wife who was killed in a car accident. “I’m surprised he put that out there,” says Joseph.

The documentary Negro Terror premiered in November, 2018 at Playhouse on the Square during the Indie Memphis Film Festival, with the band providing a live soundtrack to the packed house. It would go on to win the festival’s Soul of Southern Film Award.

This spring, Omar was hard at work preparing the release of Negro Terror’s debut album Paranoia. “He had back problems,” says Fields. “Last summer, at one of these little funky-ass festivals, he fell through some stairs and fucked up his leg real bad…He was getting better. He just got back in the gym. He was already down 30 pounds. We were about to hit the road hard, and he was ready for it.”

In mid-April, he hit a wall. “His back was hurting,” says Joseph. “We usually play three church services on Sunday. We played one and he was like, man, I feel bad. I don’t think I can make it.”

Omar returned to the family home to get some rest. His brothers later discovered him laying on the floor. “He said he felt like he had a pinched nerve in his side. I asked if he needed to go to the hospital, and he said nah, he’d had this before. It was something that would die down quick. After a couple of days, he still wasn’t feeling well. He was still in the same spot, it looked like. Then we were like, nah man, we gotta get an ambulance.”

[pullquote-8] An untreated sore on Omar’s back had led to a staph infection which spread quickly. In the hospital, he suffered a stroke and ended up in the ICU. As his condition deteriorated, word spread that Omar was in trouble. CCDE had fought to get Kween Jasira and Ras Empress included on a show they were opening with Jamaican dub musician Jah9. They eventually arranged to give their protégées half of their set. “When Omar fell ill, we had to open up the whole show,” says Jasira. “I was calling and checking in every day. I think the thing that made it the toughest, the night we played the Jah9 show, word was he was turning the corner. He was out of ICU, and the breathing tube had been removed. I was not ready for it to turn the other way the next day.”

Joseph says, “While he was in the hospital, he did nothing but crack jokes. We were watching TV and praying, just being as positive as possible. It was a time when you would think he would be depressed, he was trying to stay positive about everything…I want to say the day before we passed, he was on the phone with Donnon, our drummer. He said, ‘When I get out of this bed, we’re going to start working on the Chinese Connection Dub Embassy record. It’s way overdue. People are waiting on it’…He said, ‘This happened for a reason. It’s telling me that we need to keep on what I’m doing, but we need to bring light to the dark times. That was what inspired him. He wanted to get it out to the masses. We said, we’re with you for the long haul.”

[pullquote-9] Omar Higgins died on Thursday night, April 18. “We were with him until he passed,” says Joseph.

As the news leaked out over the weekend, there was an anguished outpouring of love from Memphis musicians and admirers on social media. “Omar was the powerful voice who stood up for you, even when you couldn’t stand up for yourself,” says PreauXX. “That’s something I’m always going to carry in my heart, and I think everyone who knew Omar knew that about him.”

“For a couple of days, I couldn’t wrap my head around the why,” says Kween Jasira. “Now, I’m just trying to accept it and be there for his family. I want to make Omar proud. They say death isn’t final. As long as you speak their name, and talk about them, they’re never truly dead. That’s what we can do to keep Omar alive, with the music that he loved, and to carry the same Omar spirit along with that.”

[pullquote-10] “I’m still processing it,” says Donnon Johnson. “I love Omar so much, as a man, and what he brought out in me as a musician, that my heart is going to have to find a new way to break.”

Chris McCoy

Chris McCoy

Omar Higgins plays the Green Room at Crosstown Concourse in March, 2019. It would be one of his last shows.

“I told somebody today, ‘God sent him to me,’” says SvmDvde. “I had to meet him and learn from him in order for me to get where I needed to be. He opened my mind completely. I could talk to him about anything. He guided me spiritually, musically, everything.”

Fields says Negro Terror cannot continue without Omar. “Negro Terror has died and been reborn. Look at what’s going on in pop culture. The Lil Nas X kid? He’s Negro Terror…The idea of Negro Terror isn’t even to be a cool punk band with a cool logo. It was showing black kids that they could do anything they wanted to without worrying about it being a white space. There ain’t no such thing as a white space.”

[pullquote-12] “Not only did he have the skill and the talent, it was not in vain. He was using his talent to inspire and build community. He was giving of himself, sometimes not to his advantage. He was skilled, and humble,” says Eso Tolson. “That spirit, what he was about, his music, will carry on. Those who didn’t know him will come to know him with the stories that will be shared.”

Fields says he got to say goodbye to Omar. “He came to me in a dream. He looked kinda down, so I gave him a hug. ‘I got you,’ I said. He said, ‘No no no. I got YOU, forever.’ I hadn’t had a dream since.”

Omar Higgins

A memorial for Omar Higgins will begin with a Beale Street parade at 10:30 AM on Tuesday, April 30, followed by a reception at I Am A Man Plaza at 11:00 and funeral services at Clayborn Temple at noon.

Chris McCoy

Chris McCoy  Chris McCoy

Chris McCoy  Chris McCoy

Chris McCoy  Laura Jean Hocking

Laura Jean Hocking  Chris McCoy

Chris McCoy  Chris McCoy

Chris McCoy  Laura Jean Hocking

Laura Jean Hocking  Chris McCoy

Chris McCoy  Laura Jean Hocking

Laura Jean Hocking  Chris McCoy

Chris McCoy  Chris McCoy

Chris McCoy  Laura Jean Hocking

Laura Jean Hocking  Troy Glasgow

Troy Glasgow