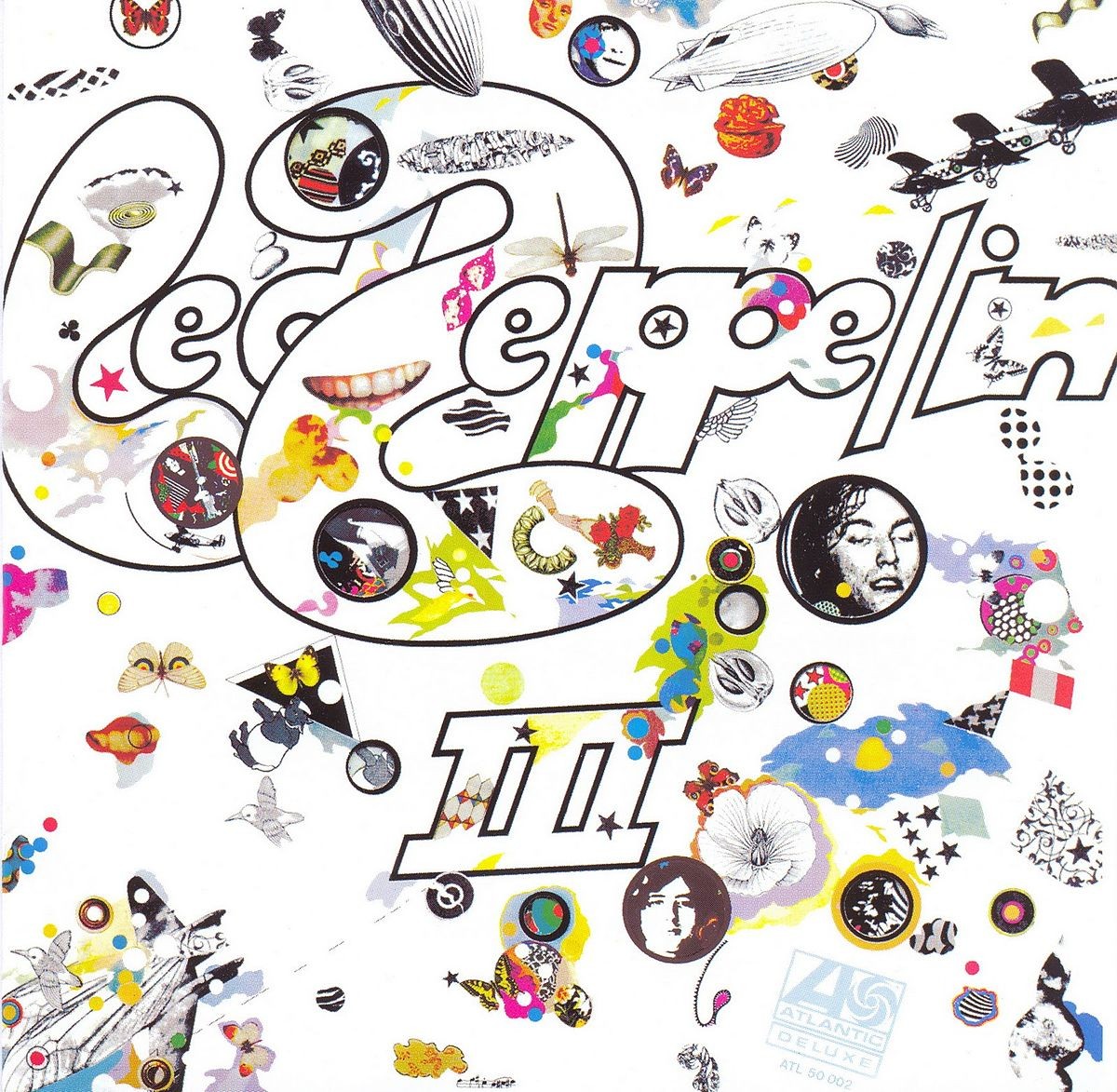

Ah, to settle into these idyllic fall days, with Led Zeppelin ringing in the air. October 5th marked the 50th anniversary of the release of Led Zeppelin III, mixed and mastered at Ardent Recordings, prompting many to reminisce about the impact of the album and the band on the Bluff City. Many a muso has dusted off an old copy with the spinning-wheel cartoon cover sleeve, so at odds with the album’s very autumnal mood, all bracing shrieks and riffs and crackling acoustics ’round the fire.

Terry Manning was the engineer for some of the album’s overdubs, and all its mixing and mastering, and when we spoke, he shared too many memories to fit in one article. Most of the tale can be read in Memphis magazine’s November cover story, taking you all the way from the Yardbirds in Kentucky to Jimmy Page having Manning inscribe messages onto the vinyl’s inner groove. But space did not allow for one bit of our conversation, concerning the interest in Led Zeppelin expressed by one Chris Bell. The founder of Big Star was himself a great fan, even known to spontaneously break out into the entire guitar solo of their song “Heartbreaker” (as described in Rich Tupica’s Bell bio, There was a Light).

When I spoke to Manning about mixing the album and the band playing in Memphis, he brought up Chris Bell:

Memphis Flyer: Did it create quite a stir around town, the fact that Jimmy Page was in town?

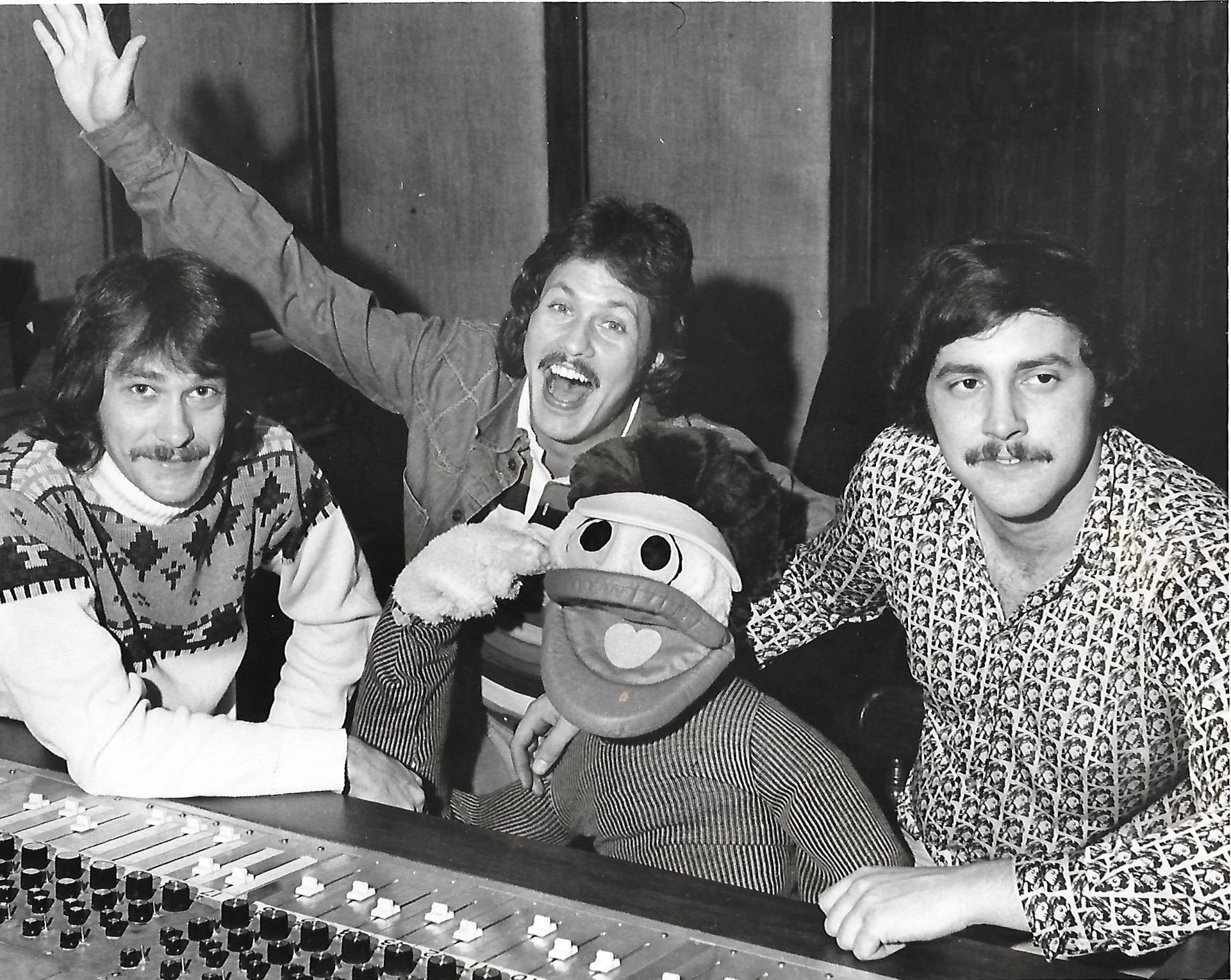

Terry Manning: You’d think it would create a stir like that, but it didn’t really. Jimmy wanted it kept quiet and we had work to do. There wasn’t any partying and meeting people and things. John Fry was not even there. He didn’t come for the session in any way. He stayed out. Once we were there, I locked the door and other people didn’t come in. It was very under the table. Kept quiet.  courtesy Terry Manning

courtesy Terry Manning

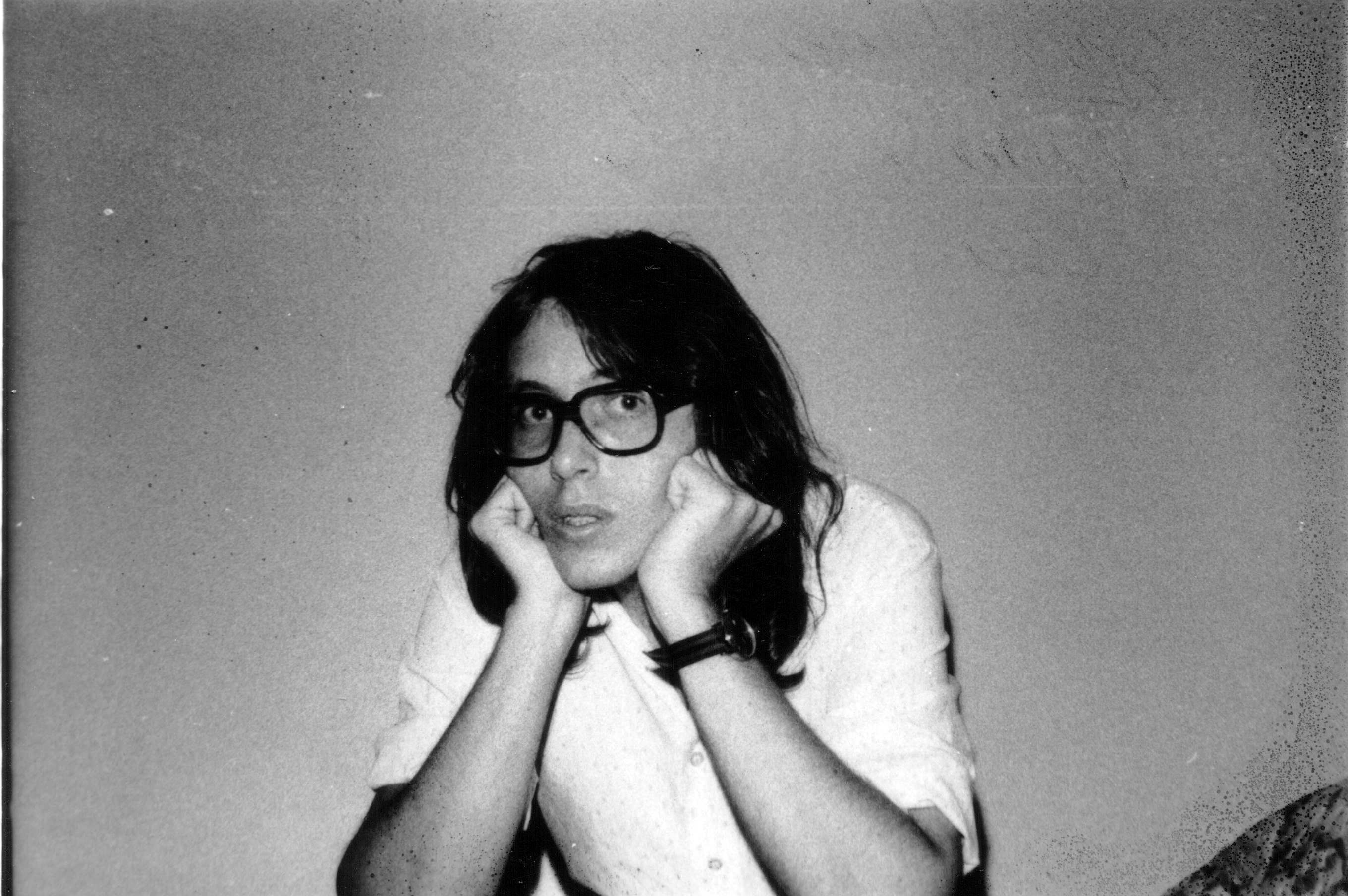

Terry Manning at the Ardent mixing board, 1971

Now, Chris Bell did know about it, and I think he came in for a second once. But I know later, when they were on tour, and Zeppelin played in Memphis, Chris came over to my house. Because Jimmy and his then-girlfriend Charlotte came to my house for dinner after the Led Zeppelin concert. And I’d had an Indian meal catered by an Indian restaurant, which you couldn’t get in the U.S. on tour very much then. So I’d told Chris to stay away, but he couldn’t help it. He came by sheepishly, with a bottle of wine. So we let him in, and Jimmy and Chris and I hung out. We listened to Gimmer Nicholson all night. And Ali Akbar Khan.

Josh Reynolds

Josh Reynolds

Terry Manning

I told him, do not come. And this was after the concert, not during the recordings. But he just couldn’t help it. And I can’t blame him. Of course not! Now, years later, I’m so glad he did. It’s a wonderful memory, to be thinking of, two o’clock in the morning, Jimmy Page, Chris Bell, and me sitting on the floor, listening to Ali Akbar Khan and Gimmer Nicholson. Acoustic and Indian music, mostly.

Another renowned Memphis guitarist, a generation or so removed from Chris Bell, also noted his connection to Led Zeppelin III last month. On October 5th, guitarist Steve Selvidge (The Hold Steady, Big Ass Truck) celebrated his wedding anniversary with an online post and noted they had married on “the 32nd anniversary of the release of Led Zeppelin III.” An auspicious day, indeed, and it prompted Selvidge to recall the profound effect the band (and guitarist Jimmy Page) had on his musicianship.

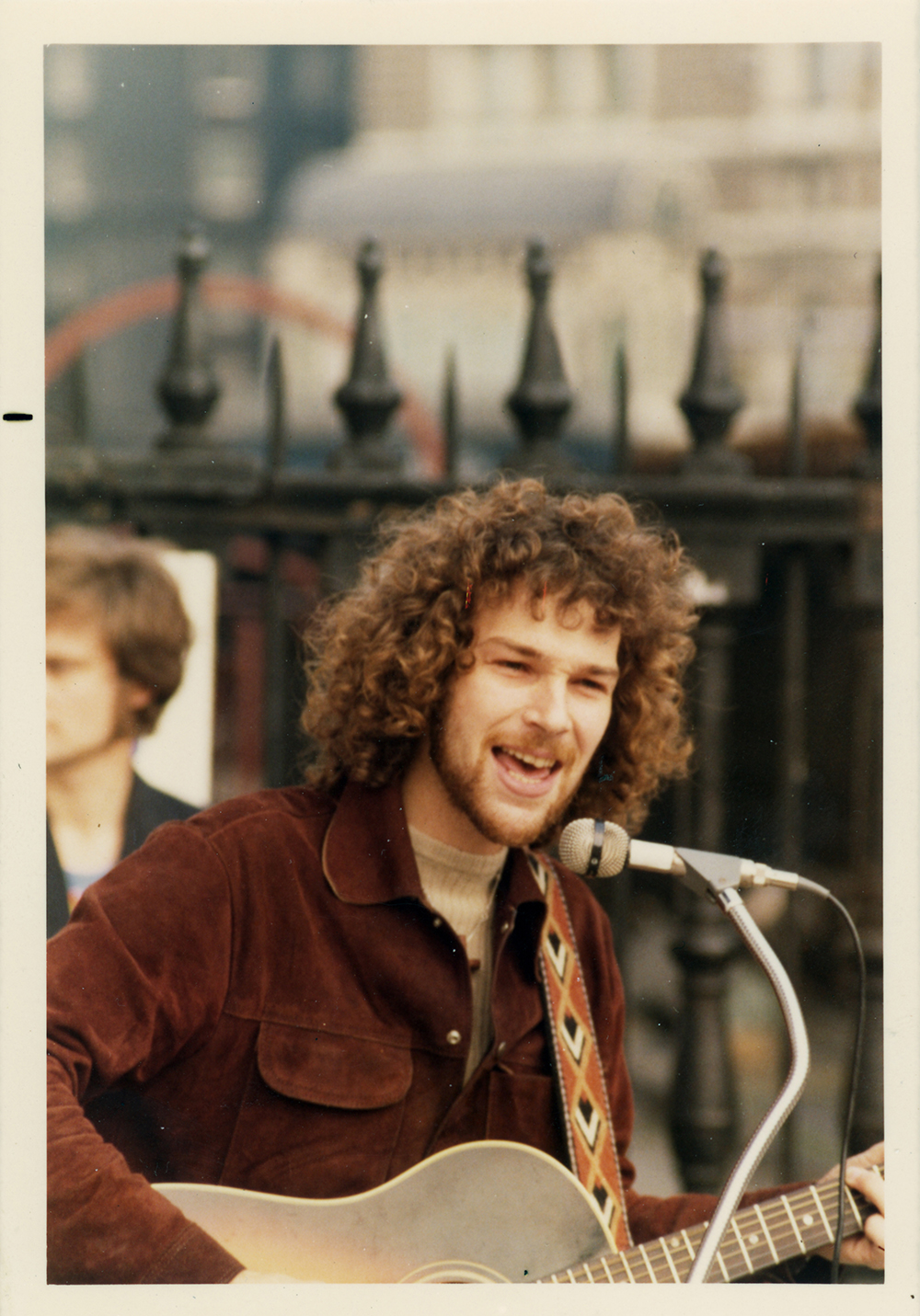

And the very different effect they had on his father, the late Sid Selvidge.  Rich Tarbell

Rich Tarbell

Steve Selvidge

Memphis Flyer: Do you still have your old copy of the album?

Steve Selvidge: If you’re talking about Led Zeppelin III, that’s a piece of vinyl that I purchased when I was young. I think it was in fifth grade when it first seeped deep into me. I had just started playing guitar. Certainly by sixth grade, I was definitely way into it. I remember a friend’s older brother had The Song Remains the Same [the live soundtrack album of the film of the same name], and I remember playing that. Someone once said, “Zeppelin is nothing if not older brother rock.” I had lost my copy of Led Zeppelin III for years, but my brother was moving and found it. I bought it at Pop Tunes. Talk about the opposite of 180 gram vinyl pressing, this was just the floppiest disc. It did have the sleeve with the spinning wheel! And it had the Crowley quote, too [inscribed on the vinyl].

Do you think it holds up?

I’ve read all the press. I can almost see the words on the page, I’ve read it so many times. And I think they were unjustly criticized at the time, Oh yeah, Crosby Stills & Nash and Joni Mitchell had hits, so they jumped on that bandwagon. And Jimmy Page was like, ‘This acoustic music’s on all of our records. It’s not like we picked up acoustic guitars out of nowhere.’ I mean, ‘Ramble On,’ man! But the first two were released at the beginning and end of 1969. They’re companion pieces. One was born out of Jimmy Page’s initial plan, and one was born out of the road. But I do agree that III was where Plant was able to emerge more fully formed. And honestly I think that’s also when he had more of a sense of job security.

Because, from what I’ve read, even through the second record and touring, it was like, this is Jimmy’s band. Peter Grant’s laying down the law, like, ‘Dude, don’t think you can get comfortable.’ But with III, Robert started to assume this thing of the front man. The center piece, the Golden God. It was a crazy time. That was back when a guitar player could be famous just for being a guitar player. Not just famous, but people who weren’t musicians knew who he was, because they’d tracked his progress in the Yardbirds. It was this burgeoning underground scene. So there were people who knew Led Zeppelin because of Jimmy Page. But then Robert transitioned into that pop consciousness. And it was years, for me, before I realized that the average person takes a band on its front man. I was like, ‘Wait, there are people who know Led Zeppelin and don’t know who Jimmy Page is? Every guitarist in every band is just as important as the singer, right??’ It turns out I was mistaken about that..

And this is speaking to my middle-aged-ness, but I think that’s probably their best nighttime record. With technology these days, streaming music is daytime whatever, just put on something that’s rockin,’ get the dishes done. But for me, vinyl is the nighttime thing. It’s the kids have gone to bed, decompressing and talking about the events of the day, and what are we gonna put on? Zeppelin III is good cranked up, and it’s also good at low volumes.

‘Friends’ was the first time they used a tuning not based on British whatever folk traditions. It was more of a nod to Indian music. And Page was really into Indian music well before the Beatles were. He tells the story of going to hear Indian music and it was him and a bunch of old people. He was the only young person there. So, ‘Friends’ is a big one in terms of that.

The vocal on ‘That’s the Way’ is so gorgeous. As a lifelong Page disciple, as I get older, I get more and more fascinated by Robert Plant. Some say that his wail on ‘Since I’ve Been Loving You’ is when he started to lose his voice. His voice changed radically, because they toured so much. He didn’t have a vocal coach. He was just smoking and drinking and shouting. So by ’72 his voice had changed. And some say that shriek on ‘Since I’ve Been Loving You’ is the swan song, if you will.

It took me a long time to come to terms with that recorded version of ‘Since I’ve Been Loving You.’ ’Cause I was such a disciple of the movie, the Song Remains the Same, and that version of the song from ’73 at Madison Square Garden, I just loved it so much. It’s super stoney. For whatever reason, John Paul Jones didn’t have a [Hammond] B3 [organ] with him. On the ’73 tour, it was all Fender Rhodes [electric piano] with foot pedals. You know, the B3 is like, I’m gonna put you in a specific place right now. And for the longest time, I didn’t want to hear it. Because I was so in love with the Rhodes and the stoney vibe of Madison Square Garden. But now I’ve come to respect it for what it is.

And the guitar solo on that [album version]. That song is one of Zeppelin’s greatest moments. Plant will tell you that. That guitar solo is one of Page’s greatest moments for sure. And that’s what brought me back to that version. It’s the perfect mixture of his technique, which also changed, and his emotion. Of all the big three guitarists in his class, he wrought the most emotion. And that is right there.

Did Lee Baker ever talk about Led Zeppelin?

I probably brought it up some. I knew that Lee Baker played a Sunburst Les Paul from the ’50s. A 1958-60 Les Paul Sun Standard … the significance of it. That’s what Jimmy Page was playing, and Lee Baker had the same kind of guitar. And it was rare. I know he knew Page was bad, but he was into other things.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

The late Sid Selvidge, with son, Steve

Your dad, Sid Selvidge, was a pioneering performer of the blues, among other things. Did you listen to Zeppelin with him?

I played a lot of Led Zeppelin at my house when I was a kid. And my dad happened to be a pretty proficient singer in his own right, with pretty strong opinions about other singers. And he did not like Robert Plant at all! His thing was, ‘I know he can sing! I’ve heard him, he can sing! He just does all that puke music, man!’ That’s what he called it, ‘Puke Music.’ Like he’s straining so hard he’s gonna puke, you know?

But the final nail in the coffin was when it got to the last song, ‘Hat’s Off to (Roy) Harper,’ which is just Fred McDowell, ‘Shake ’Em On Down.’ And man, would that make him mad! He was just like, ‘This British motherf*cker!’ He was just mad about it, man! I remember him specifically zeroing in on it. I remember exactly where I was sitting, in front of the turntable, looking at this old decorative lamp. And he was just so pissed off at the way they were interpreting Fred McDowell. ‘Lee Baker could just smoke this kid!’ They were just defiling Mississippi Fred McDowell. I think it was the histrionics of Robert Plant that really did that. That’s just how he sings.

I will say, Robert Plant’s voice did change. And I kinda liked it, because, as a connoisseur of bootleg recordings, he had the power, and he wasn’t always judicial with it. So there’s a lot of him going over the top, screaming, getting super high, and wailing and stuff. That’s why, for me, ’73 is the peak year. His voice has changed, and he can’t just go high all the time. So it forced him to get creative with the melodies, and kind of lay his shit back a little bit. Which I like. ’Cause I do like it when he croons. And Jimmy Page’s tone was at its apex, and his playing had changed. He laid off some of his go-to things, and was stretching out a little bit more. Then by ’75 it just all goes to shit, in my opinion. But Plant’s another polarizing one. I don’t know, I’ll sit through a lot of bad singers to hear the guitar that I want.

courtesy Terry Manning

courtesy Terry Manning  Josh Reynolds

Josh Reynolds  Rich Tarbell

Rich Tarbell  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  courtesy Andy Black

courtesy Andy Black  courtesy Andy Black

courtesy Andy Black