There is no doubt in my mind that children will have to deal with the long-term social effects of the COVID pandemic more than any other group. Just like there was an entire generation that was turned into hoarders because of the Great Depression, there are kids who are going to come out of this thing addicted to putting hand sanitizer on everything. They may even continue wearing masks past the point of needing them. After my grandmother died and we cleaned out her house, we found hundreds of Ziploc bags full of crumbs she saved from restaurants. She knew good and well she was never going to eat those crumbs, but she had been turned into a weirdo from her childhood of rationing. When it’s my son’s time to go, his grandchildren are going to find barrels of industrial cleaner and hydroxychloroquine in his cabinets.

We are only now starting to see the damage of what has happened to our children after being isolated for more than a year. There were a few times when my son got so frustrated at being distanced, that he and some other kids rebelled and ran through the neighborhood together just to feel what it was like to play. Other than that though, he has been kept away from most human contact aside from what you can get through a telephone. No carousel rides at the mall, no amusement parks, no movies, my 6-year-old son wasn’t even allowed to go to a playground … until now.

For the first time in more than a year, we took our son down to the local playground. There were maybe 20 or 30 kids there, all emerging like the cicadas, buzzing around one another and squealing. It was nice to hear the laughter of a group of children. I didn’t realize that I missed it. Then my son comes running up in tears. Here we go.

Apparently there was some kid running around who was in his kindergarten class in the “before times.” This kid, let’s say his name is Toby — it isn’t but for the purposes of this story it is. It’s a name like that for sure. I guess my son went to talk to this Toby, and of course this Toby didn’t remember him. They used to sit together every single day for eight hours, and the kid had no recollection of my son. Yes, this was a year or so ago, but my son was confused. Devastated. Crying his eyes out. He thought he had a true friend in this Toby.

Now I can confirm that Toby was in his class because I spent a good hunk of time volunteering down there. I am also not surprised in the least that this kid didn’t remember my son. I am kind of shocked that he remembered his own name. You know the type, Kool-Aid mustache, boogers hanging out of his nose. Pushy. I told my son to not worry about it and just play with some other kids. Then this kid starts picking on my son. Taunting him. All the kids are playing tag, and this Toby with his red mustache is hurling insults. That kind of stuff doesn’t fly with me, and I learned that intolerance must be on a genetic level.

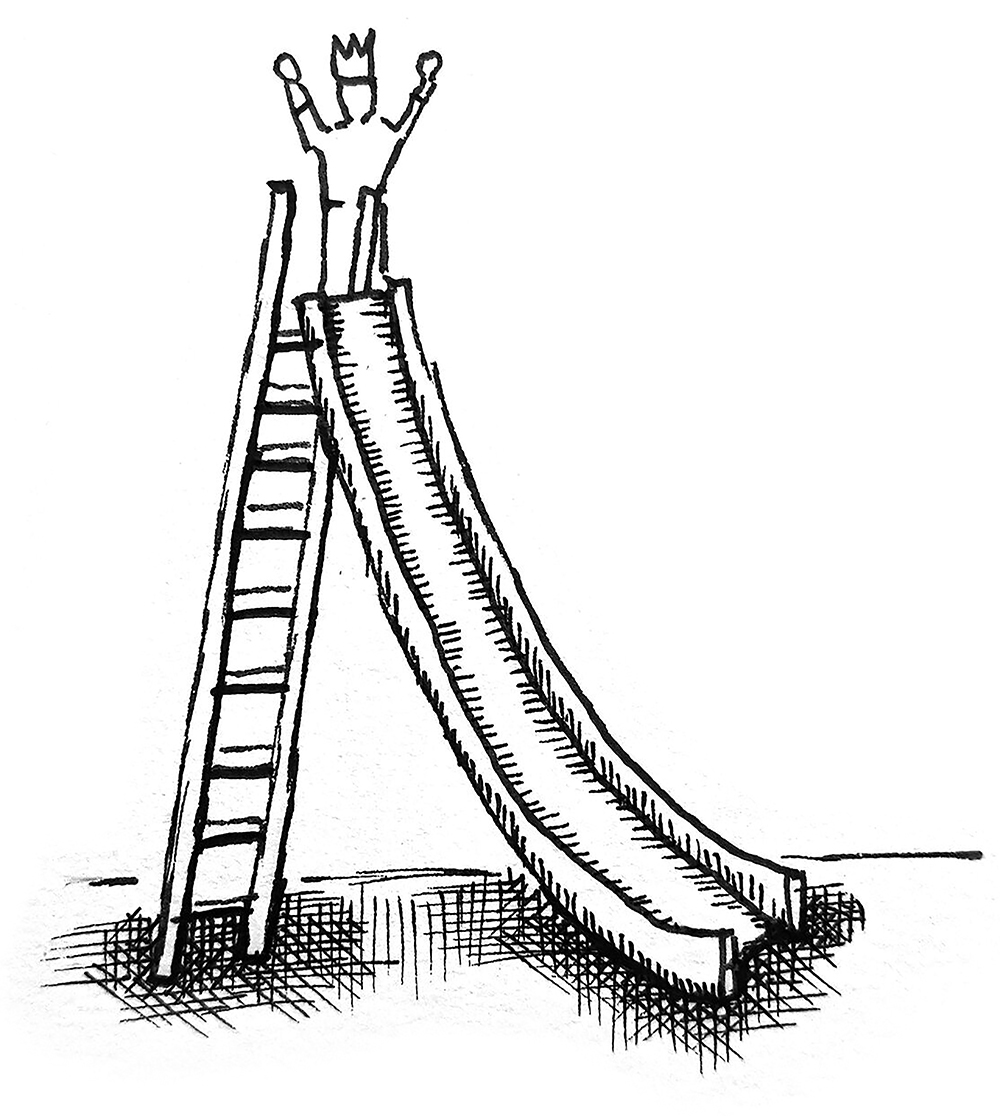

I then watched as this 6-year-old of mine managed to herd all the other kids on the playground. One by one, he goes up to all 20 or 30 of them and somehow turns them all against this Toby. My son climbs to a lookout position high on top of the tallest slide and is commanding this group of children to run after and chase this kid. At first the mood was jovial, but eventually Toby became overwhelmed by the force and ran away bawling his eyes out, tears washing away his mustache, tripping over his flip-flops.

I am well aware that this was a teachable moment and I shouldn’t laugh. If I did, I made sure my son didn’t see me do it. When he finally climbed down from his command center, I asked him why he did what he did. Maybe he didn’t even know what he did? He’s 6. Well, he did. He knew. His answer was, “Toby told me he didn’t remember me, but next time, next time he will.”

What have I done?

Chris Walter is a Southern writer and artist. His recent book, Southern Glitter, and more can be found at his website kudzuandclay.com