Mention director Wes Anderson, and eventually someone will say he’s “twee.” What does that mean, exactly? The Merriam-Webster definition of “twee” is “affectedly or excessively dainty, delicate, cute, or quaint.” The word itself is thought to come from the way a small child pronounces “sweet.” Anderson’s films, which began with Bottle Rocket in 1996, were sort of retroactively lumped into a poptimist mini-movement that arguably began with a 2005 Pitchfork article titled “Twee As Fuck.”

But I’ve never thought of Anderson as particularly twee in the way, say, Shirley Temple was twee. Yes, he’s meticulous in his visuals, and childhood has been a recurring subject for him. You can tell he’s someone who has cultivated what the Buddhists call “the beginner’s mind,” staying in touch with the awe of youth most people lose as they grow older. But there has always been a darkness underneath the curated surface of his films. The Royal Tenenbaums is about a family trying to deal with the aftermath of growing up with an abusive drunk father. The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou is about failing to deal with failure. At the end of The Grand Budapest Hotel, the hero M. Gustav is summarily executed by Nazis, and the narrator Zero’s wife and child die in a flu epidemic. Moonrise Kingdom is … okay, I’ll give you Moonrise Kingdom. But it’s also a major fan favorite, and one of the director’s biggest financial successes.

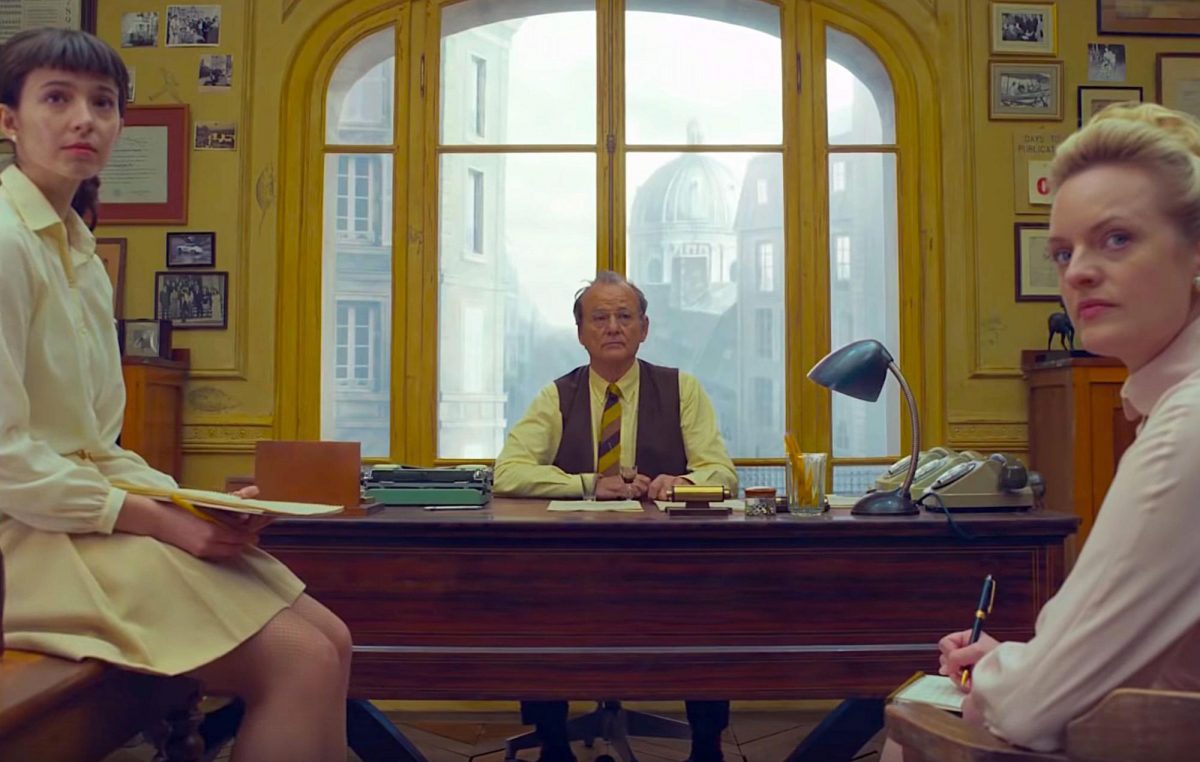

Anderson’s latest film is The French Dispatch. I’m going to go ahead and cop to being biased toward this one, because it’s about magazine writers, and that’s what I am. (Read me in the pages of Memphis magazine!) Befitting the eclecticism that is the magazine form’s bread and butter, it’s an anthology movie — an exceedingly rare bird these days. It begins with the death of publisher Arthur Howitzer Jr. (a magisterial Bill Murray), whose will specified that his magazine, whose name is the film’s full title, The French Dispatch of the Liberty, Kansas Evening Sun (okay, that’s pretty twee) would shutter after one final issue which re-runs the best stories from its long history. First, we get Owen Wilson narrating a cycling tour of the fictional French city of Ennui, which lies on the Blasé river, because of course it does.

Then, Tilda Swinton delivers an art history lecture on the origin of the French Splatter-School Action Group. The wild painters were inspired by Moses Rosenthaler (an absolutely brilliant Benicio Del Toro), an insane, violent felon who takes up painting to pass the time during his 30-year prison sentence. His first masterpiece, a nude portrait of Simone (Léa Seydoux), a prison guard who becomes his lover and muse, is discovered by Julien Cadazio (Adrien Brody), an art dealer imprisoned for tax evasion.

In “Revisions to a Manifesto” Frances McDormand plays journalist Lucinda Krementz, who abandons neutrality by having an affair with student revolutionary leader Zeffirelli (Timothée Chalamet) of the 1968 “chessboard revolution.” Due to the students’ lack of demands — beyond unlimited access to the girls’ dorm — Krementz drafts the revolutionary manifesto herself.

“The Private Dining Room of the Police Commissioner” is the least coherent episode, but it features a killer James Baldwin imitation by Jeffery Wright as Roebuck, a writer whose assignment to do a profile on chef/gendarme Lt. Nescaffier (Stephen Park) spirals off into a tale of kidnapping and murder, with very little actual food content.

“Twee” implies closed off, hermetically sealed, and precious. The French Dispatch is anything but claustrophobic, even in the scenes set in an actual prison. This is Anderson’s most expansive and generous work, teeming with life in all directions. Heavy hitters like Willem Dafoe, Griffin Dunne, Christoph Waltz, Elisabeth Moss, and the unexpectedly dynamic duo of Henry Winkler and Bob Balaban appear for only seconds at a time. The dizzying array of faces flashing across the screen led me to count the acting credits on IMDB. I gave up at 300. While there are some great shots of the actual French countryside, most of the action takes place on soundstages. Nobody does set design like Anderson, and all kinds of wonders are on display, from tiny dioramas to livable multi-story cross sections.

The French Dispatch is a love letter to the golden age of magazine journalism, and it made me think I was born in the wrong era. But the underlying theme is revolution in all its forms, from the students manning the barricades to new artistic movements springing from a prison riot. Maybe the critics are right, and all this stylized attention to detail designed for aesthetic shock and awe really is “twee,” but if so, it’s twee AF.