In the ever-changing world of popular hip-hop, trends tend to come and go as fast as the one-hit wonders who introduced them. Hip-hop artists fearing a short shelf life can often jump the shark and get too out there, or more dangerously, stay in their comfort zones and be forgotten in just a few months. In a genre where the free mixtape reigns supreme, artists walk a delicate line of keeping things interesting and current, all while trying not to sound too much like the next MC doing the same exact thing.

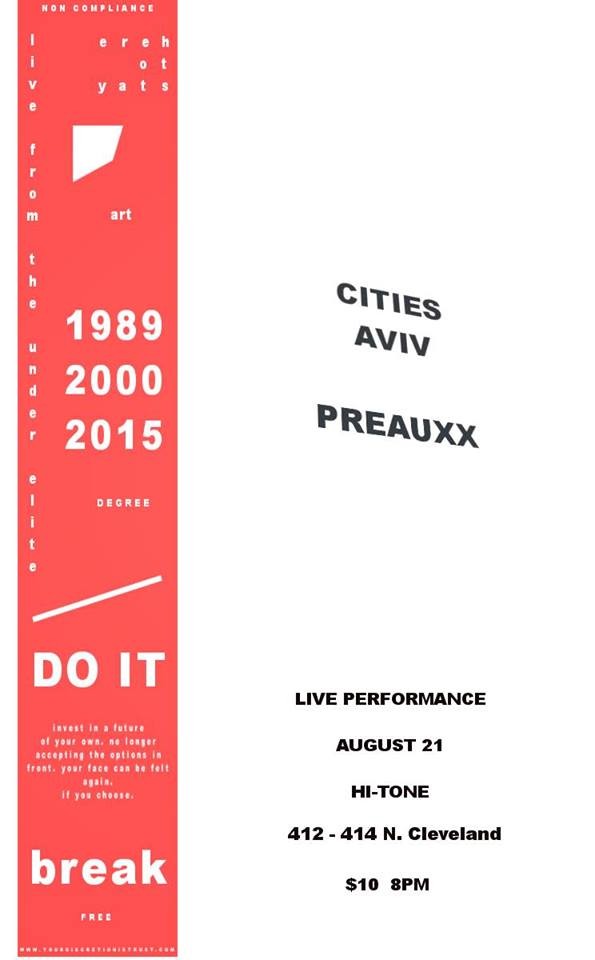

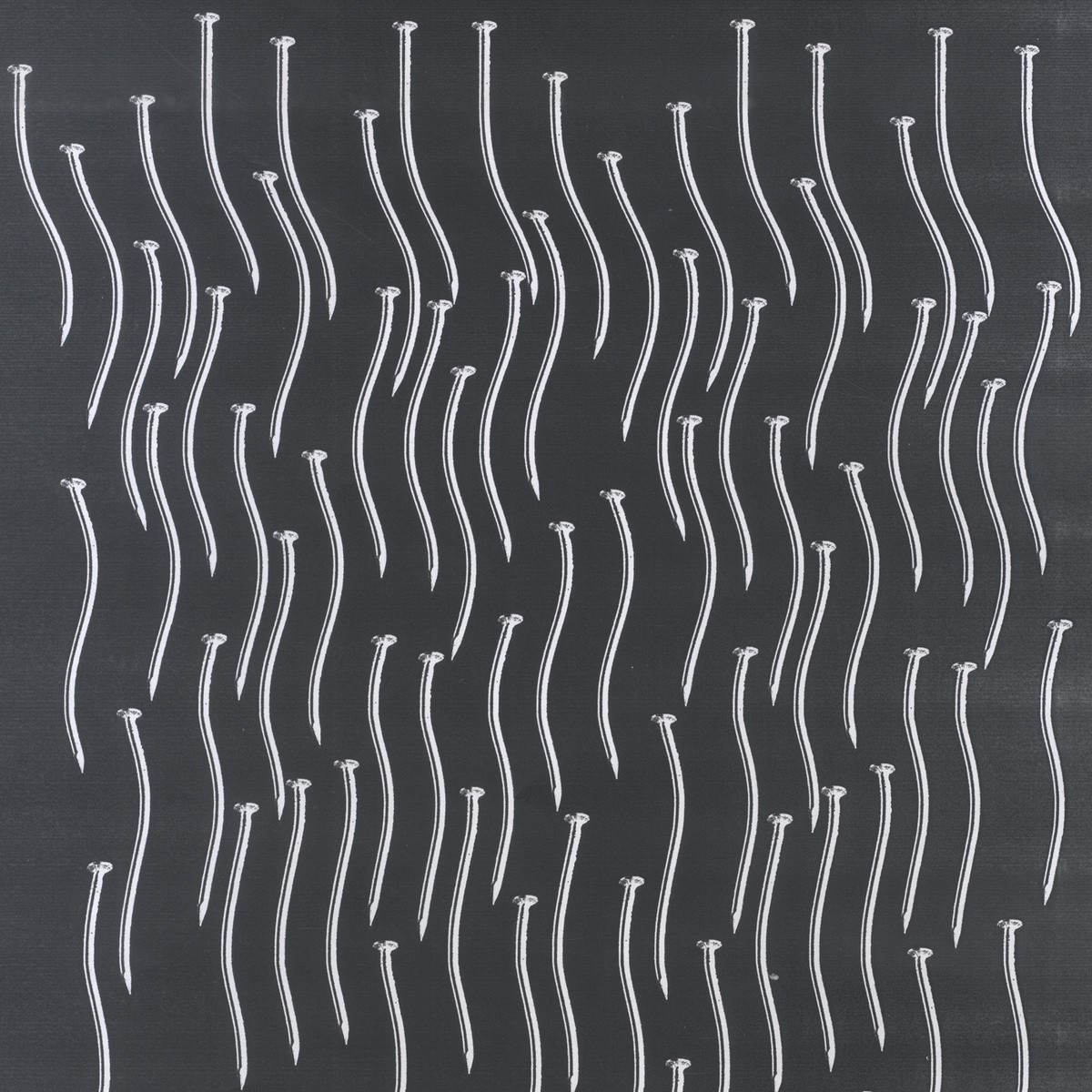

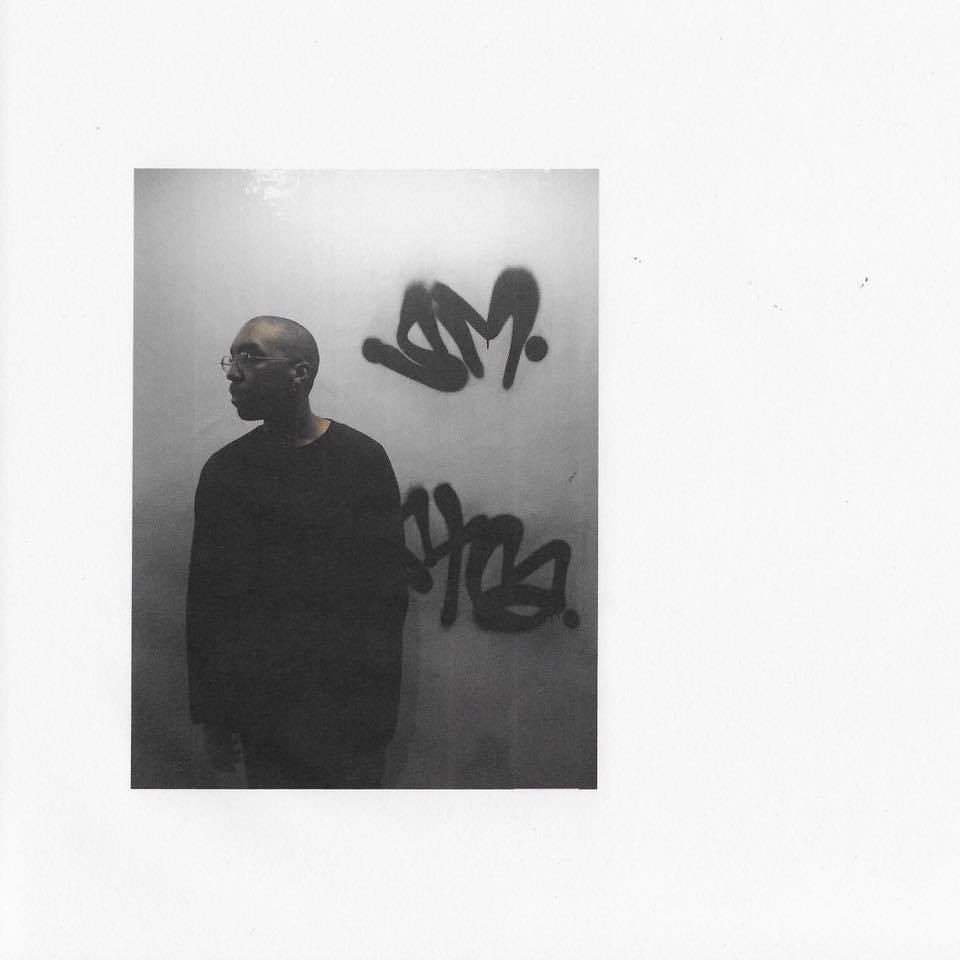

With that understood, it’s no wonder that Gavin Mays’ Cities Aviv project has taken on many forms since he dropped his first single, “Coastin” in 2011. Through each change, from the chill, smoked-out vibes of Digital Lows to the aggressive post-punk sampling of Black Pleasure, critics have struggled to pin-point exactly what microcosm of hip-hop Mays fits in. He’s been described as “cloud rap,” “backpack rap,” and most recently, “black punk.” And while all of those genres sound a little perplexing, (and a little racist), Mays has learned to embrace the fact that his music isn’t easily pigeon-holed. Under the phrase “pop music for the unpopular,” Mays seems content to do whatever comes to him, wearing his outsider status proudly on his sleeve.

We sat down with Mays to talk about his latest album, Come to Life, and what it was like making the transition from Memphis, Tennessee to Brooklyn, New York.

Memphis Flyer: As someone who has been involved in the rap and hip-hop scenes in both New York City and Memphis, what are some things you’ve learned as an artist trying to be heard?

Mays: Moving between two cities with polar realities, I feel that I learned to trust in my instinct more. New York greets with a lot of promises and Memphis leaves you with a boulder on your back larger than the city itself. That boulder being the weight of the past, which Memphis still harnesses to this day. I had to let all of that go. No one and nothing other than myself can define the project.

A phrase I’ve seen you use widely is “Pop Music for the Unpopular.” Do you still feel like you’re making rap music for a niche audience, instead of something more radio friendly?

At this point where the niche audience is becoming more and more radio friendly, I feel that I make music more for myself. If that niche audience identifies with certain signifiers buried within my sounds, then I am more than welcoming. I will say that every new song I make is in one way striving for this moment of destruction of whatever today’s pop standards are. A lot of that inspiration comes from the 1984 film Decoder.

You just released your third record since moving to New York City. When and where did you record your latest record, Come to Life? How long of a process was it?

I recorded the entire record over the past year in the Bushwick neighborhood of Brooklyn. I was in and out of the city via my basement headquarters which lay nestled in an art slum. The experience definitely crafted a lot of the subject matter of the album. Self-realization. Anti-fashion. Anti-authority.

Come to Life came out last month via Young One Records, but up until then it seemed you were hesitant to sign with a label for more than one release. What changed with Young One? Will you be working with them in the future?

The deal with Young One that I signed was only for one release. To be honest, I saw it as a stepping stone to release more physical work. I reached a point where I wanted my ideas to transcend from being just ideas to tangible objects. Objects to perpetuate the total project of Cities Aviv. I’m still pretty weary of the industry to an extent, because in the end I don’t think they understand what I am or what I am doing.

What do you make of music writers calling your type of music Black Punk? What does that mean to you?

I think it is funny seeing that no one would ever call a modern band like OFF! “White Punk,” just speaking in terms of modern acts. That aside, there is something to be said about a resurgence of black artists lending a more aggressive tone to non-guitar based styles. In the end it is all art and expression.

While something like Black Punk might not be the most accurate description, your music has definitely taken a more aggressive tone since 2011’s Digital Lows. How has moving to New York City had an impact on the way your music has progressed?

New York has simply helped me refine this into a more singular channel. To the few people that know, before I left Memphis a lot of the last shows here were in the midst of recording my album Black Pleasure. Distortions took the forefront as well as pure vocal aggression. On [the album] Digital Lows I delivered my voice within a rap package while [the albums] Black Pleasure and Come to Life simply delivered everything. Black Punk is an easy term for writers looking for a label. I’m not offended, but I’m not a punk.

How has Come to Life been received so far in the short time that it’s been out?

So far so good. Only positive. Will be interesting to see this time next year.

What do you have planned for the rest of 2014?

I’ve already started on a new solo work, which I can’t speak of. Also new Cities Aviv pieces will be presented alongside many worldwide performances.

Trill Americana

Trill Americana  Josh Miller

Josh Miller