Hey, did you hear the one about the starlet who was so stupid she came to Hollywood and slept with the writer? As you can tell by the misogyny, that joke is very old. Here’s another one for you: What’s the difference between a writer and a savings bond? One day, a savings bond will mature and produce income.

I got a million of ’em.

In Hollywood studio parlance, there are above-the-line jobs and below-the-line jobs. If you’re above the line, that means you’re irreplaceable. Below the line, you’re an interchangeable part. Producers, directors, and stars are all above the line. Technically, so is the writer — but every screenwriter who has ever suffered in Tinseltown is acutely aware that they are at the bottom of the hierarchy, and likely to be replaced at the whim of their betters. Thus, the cliché of screenwriters as self-pitying wrecks who are too smart for their own good.

Gary Oldman is screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz in David Fincher’s Mank

Mank is the story of one of the greatest wrecks, Herman Mankiewicz, as he works on the screenplay that will become Citizen Kane. It opens with Mank (Gary Oldman) decamping to the desert town of Victorville on an enforced writer’s retreat. He’s practically immobile because of a broken leg, sustained, as we see in the first of many flashbacks, in a car accident, so he’s attended by his housekeeper, Freda (Monika Grossman), while under the watchful eye of his handler, John Houseman (Sam Troughton). He’s just getting settled in when Orson Welles (Tom Burke) informs him the deadline has been shortened from 90 days to 60 days, so he’d better get started dictating to his secretary, Rita Alexander (Lily Collins).

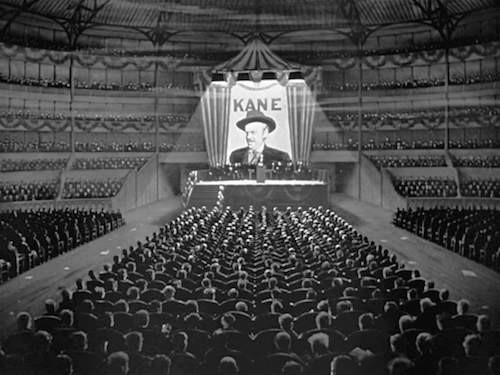

Mank’s script, called simply “American,” is about one of the most powerful people in the world of 1940: William Randolph Hearst (Charles Dance). As a top writer in the studio system of the 1930s (Mankiewicz came up with the idea of switching between black and white and color in The Wizard of Oz), he was a close friend of Marion Davies (Amanda Seyfried), a decidedly non-stupid Hollywood starlet who was Hearst’s mistress. As a frequent guest at Hearst Castle in San Simeon, Mank had a front row seat to the court intrigue of one of the richest men in the world as the Depression ravaged his fortune and political winds swirled around him.

Oldman, Arliss Howard, and Tom Pelphrey

As the flashbacks pile up, we see some of the real-life events that were inspirations for incidents in Citizen Kane. Most importantly, it was Hearst’s sudden turn from progressive supporter of Franklin Delano Roosevelt to stealth backer of California Republican gubernatorial candidate Frank Merriam over his former friend Upton Sinclair (Bill Nye) that rankled Mank.

When word spreads in Hollywood that upstart outsider Welles and old-school insider Mank were teaming up to take on Hearst, the knives come out. Everyone from his brother Joe (Tom Pelphrey) to Marion herself tries to stop Mank from committing career suicide. But even his worst enemies agree that the radical 327-page script is a masterpiece.

Director David Fincher has been trying to make Mank since the late 1990s from a screenplay by his late father Jack Fincher. The Finchers’ film finds direct inspiration in the subject, taking Citizen Kane‘s nonlinear structure of nestled flashbacks and Mankiewicz’s dialogue-driven approach to drama. Mank’s high-contrast black-and-white photography and rapid-fire wit would fit the bill if the picture was produced in 1940. Oldman is perfection as Mank, whose hard living makes him look 44 going on 74. He’s a raging alcoholic who cheekily sneaks booze onto the teetotaling ranch in a crate labeled “support devices.” He’s usually, as he ruefully observes, “the smartest man in the room,” and his lack of filter often leads to catastrophe.

The rest of the cast is equal to the task, led by Arliss Howard as chief Hearst sycophant Louis B. Mayer. The MGM head honcho gets a stunning walk-and-talk intro as he strides through the lot on the way to tell his entire company he’s cutting their pay. Howard plays Mayer as the inspiration for Mr. Bernstein in Citizen Kane, but aside from a slight Brooklyn accent, Amanda Seyfried’s Marion Davies is nothing like the hapless Susan Alexander Kane.

Mank and Marion recognize each other as alcoholic fellow travelers, existing only in this world of extravagant wealth by blind luck. They bond on a walk through the Hearst Castle zoo after being ejected from a tense dinner party conversation where the super-rich discuss the comparative threats of Soviet communism and Nazi fascism.

That’s the scene where Mank rises above film nerd-vana to deep contemporary relevance. Mank has a front row seat (and not a little responsibility) for the confluence of money and propaganda that still dominates our politics today. Donald Trump has said his favorite movie is Citizen Kane. When Kane runs for governor of New York, his biggest promise is to “lock up” his opponent. When Kane loses, his newspapers’ headlines declare “Fraud at the Polls!”

Mank is streaming on Netflix.