When pianist Christopher Parker and singer Kelley Hurt composed the No Tears Suite to commemorate the Little Rock Nine, the Black students who defied Arkansas segregationists and walked into the once all-white Little Rock Central High School in 1957, they never suspected the piece would take on a life of its own. That was over six years ago, when the couple were commissioned by the Oxford American to create the piece, and it made perfect sense to premiere it at the Central High School National Historic Site on the 60th Anniversary of the Little Rock Nine’s actions. Beyond that, however, there were no plans.

“It’s completely amazing,” says Parker of the trajectory of the suite he and his wife composed. “It just keeps snowballing, and now it’s unfolding that this thing was destined to be more than just one performance in Little Rock.” Ultimately, an album of the piece was released on Mahakala Music, but it wasn’t long before it grew into a movable musical feast which, ironically, shrank the original suite’s length to make room for local voices wherever the show took root.

Given the centrality of racial justice issues to today’s America, one might have predicted a second life for the piece, which blends orchestral jazz not unlike that of Gil Evans with Hurt’s invocations of the imagery and names from that day, inspired by Melba Pattillo Beals’ memoir Warriors Don’t Cry. Before long, Parker and Hurt sensed that they had struck a nerve. Their creation was resonating with cities across the region in ways they couldn’t have predicted. In 2019, a new arrangement by bassist Rufus Reid was presented in Little Rock, followed by a live-streamed performance in New Orleans the next year, then shows in Fayetteville, Arkansas, and Tulsa, Oklahoma, the year after that. Most recently, the project was presented in St. Louis last month, soon to be followed by a series of events in Memphis from June 10th through 14th.

At the heart of the Memphis shows will be a June 10th performance of what has grown far beyond a suite, now known as the No Tears Project, at the newly reopened Cossitt Library on Front Street. It will be an apt use of the newly renovated library space, which has been carefully crafted under the guidance of programmer Emily Marks and other team members into a multimillion-dollar arts hub featuring video labs, recording studios, and performance spaces. Indeed, it’s entirely appropriate that this space, shaped by and for the Memphis community, should play host to a project that’s become a community endeavor in its own right.

As Parker explains, it all began with the Oklahoma show. “We collaborated with these people in Tulsa, and that was really successful,” he says. “We were like, ‘What do y’all do?’ And they were more like the folk rock/singer-songwriter type of ilk. They weren’t really writing civil rights songs, but more about the moral life, folksy and spiritual. So it tied things together in kind of a cool way. People in the audience knew those people and we found some commonality.”

The St. Louis show ramped up the local involvement considerably, with the involvement of a bona fide jazz great, saxophonist Oliver Lake, founding member of the World Saxophone Quartet. “Oliver’s poetry was hitting it on the head,” says Parker, “with five poems about Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner, Ahmaud Arbery, George Floyd, and Amadou Diallo. Not only was it very piercing, but it had this dark humor.”

The original suite was shortened to make time for those poems, and others by Treasure Shields Redmond, not to mention the dancing of Ashley Tate. Now all those elements will be presented in the Memphis show, plus trumpeter Marc Franklin’s new arrangement of Memphis pianist Donald Brown’s song “A Poem for Martin.” And Parker’s especially excited about the native Memphians who’ll be in the band. “[Saxophonist] Bobby LaVell’s daddy was Honeymoon Garner! And he lived with Fred Ford, who was his saxophone teacher. Then there’s Rodney Jordan, the best bass player I ever met.” Multiple Grammy-winning drummer Brian Blade will also participate.

Parker pauses a minute to let those names sink in, happy to minimize his own role in what was originally his baby. “I mean, with players like that, all I’ve got to do is just cut them loose. I don’t have to do a thing.”

Visit oxfordamerican.org/ntp-memphis for more information.

UPDATE: Due to technical issues, the venues for this series of performances have changed:

Education Concert

NEW TIME: Saturday, June 10, 2023 – Noon to 1 p.m.

NEW LOCATION: Benjamin L. Hooks Central Library

Free to the public; seating is limited and reservations are required via Eventbrite.com

A 60-minute education concert for youth and families featuring No Tears Project ensemble members. The artists will play short selections of music interspersed with dialogue that highlights key moments and people from Memphis, Little Rock, and Jackson involved with the civil rights movement.

Community Concert

NEW TIME: Sunday, June 11 – 2 p.m.

NEW LOCATION: The Green Room at Crosstown Arts

Free to the public; seating is limited and reservations are required via Eventbrite

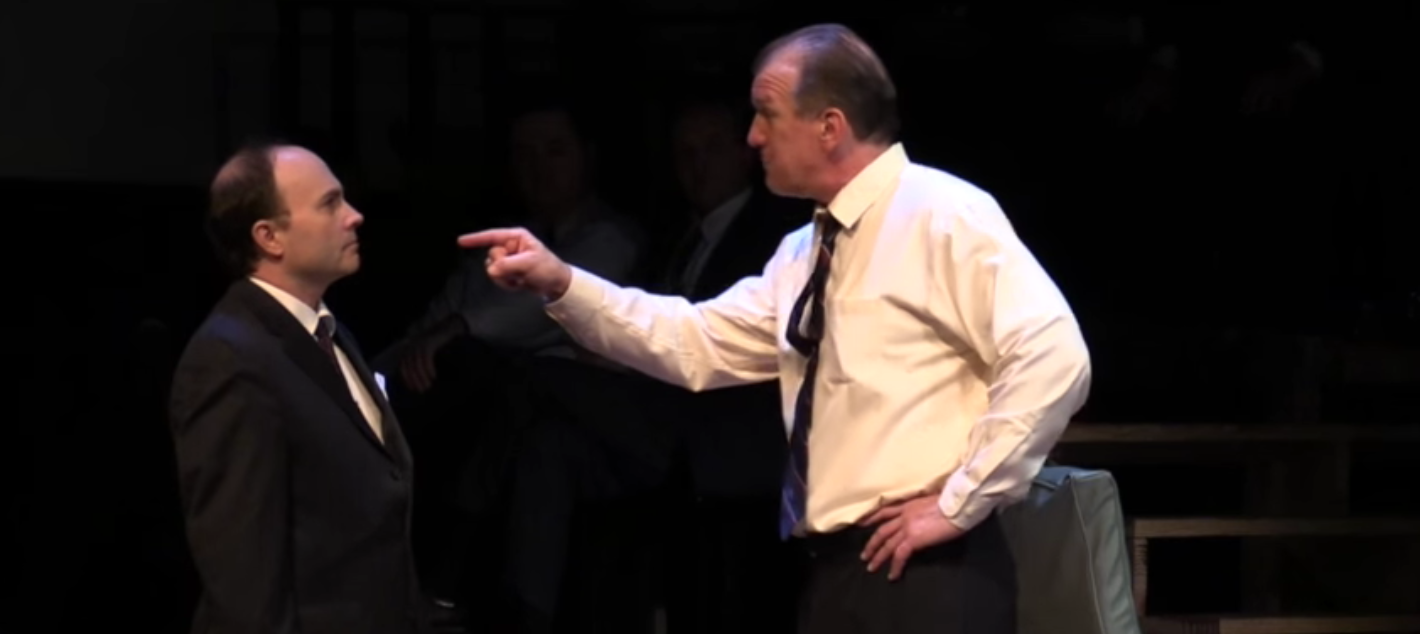

A 90-minute concert from the No Tears Project ensemble led by Christopher Parker (piano) and Kelley Hurt (voice). The band will perform the world premiere of new works written by and in collaboration with Memphis artists, including saxophonist Robert “Bobby LaVell” Garner. A new arrangement of Memphis pianist Donald Brown’s song “Poem for Martin,” written by Marc Franklin, as well as selections previously written by Oliver Lake, Parker, and Hurt, in honor of the Little Rock Nine will also be performed with poetry accompaniment by Treasure Shields Redmond, and dance by Ashley Tate.

Community Concert

NEW TIME: Sunday, June 11 – 6:30 p.m.

NEW LOCATION: The Green Room at Crosstown Arts

Free to the public; seating is limited and reservations are required via Eventbrite

A reprise performance of the same 90-minute program, designed to serve additional Memphis community members.

Recognition Before Reconciliation

Tuesday, June 13, 2023 – 6:00 p.m.

NEW LOCATION: Benjamin L. Hooks Central Library

Free to the public; seating is limited – register via Eventbrite

A panel discussion featuring civil rights heroes and activists including Memphis 13 member and daughter of Rev. Samuel Billy Kyles Dwania Kyles; Little Rock Nine member Elizabeth Eckford; and activist Reena Evers-Everette, daughter of Medgar and Myrlie Evers. Dr. Russell Wigginton, President of the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis will moderate the discussion. Superintendent Robin White of Little Rock Central High School National Historic Site will provide opening remarks and context for the discussion.

Story Time with Elizabeth Eckford

Wednesday, June 14, 2023 – 10:30 a.m.

NEW LOCATION: Benjamin L. Hooks Central Library

Free to the public; seating available on a first come first served basis.

Capping the residency in a 60-minute program for youth and families, Little Rock Nine member and heroine Elizabeth Eckford will share personal experiences and read from her book, The Worst First Day: Bullied While Desegregating Central High. Eckford, who as a 15-year-old in 1957 faced an incensed mob of segregationists and soldiers alone, will inspire the next generation with her words and story.

James Patterson

James Patterson

jb

jb