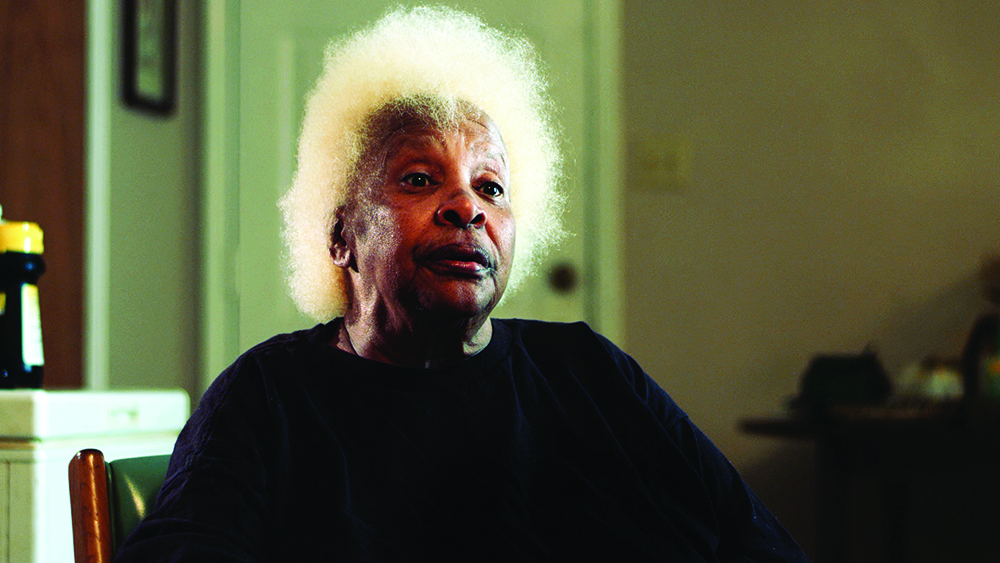

The Rev. Andre E. Johnson has been seeking answers to complex issues involving Black churches and the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement.

His research led him to write The Summer of 2020: George Floyd and the Resurgence of the Black Lives Matter Movement, in which he interviewed people involved in BLM, some of whom relied on religious narratives to describe their involvement.

Johnson previewed his book Thursday during SisterReach’s Social Justice Preacher Series held online. He is founding pastor of Gifts of Life Ministries and has authored several works and teaches at the University of Memphis and Memphis Theological Seminary.

His topic — “Rethinking Faith and Religion: The Spirituality of Black Lives Matter” — put the spotlight on Black churches and civil rights actions.

“This heightened after George Floyd’s murder,” said Johnson. “What we discovered was that for many participants the movement had not only inspired and energized people of faith and Christian traditions, but it also inspired many people and different religious traditions to re-examine their own faith journeys.

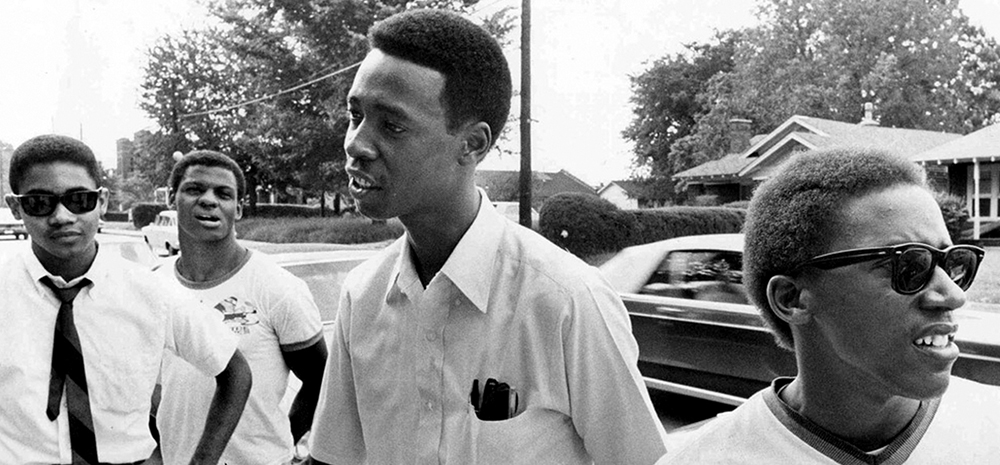

Black churches have historically been a pivotal part of social justice movements. Their involvement was exemplified during the Civil Rights Movement where they not only served as safe havens and places of hope for the fight, they also were homes of clergymen who doubled as activists.

While the church has historically played a role in the fight for equal rights for Black Americans, there have been questions regarding the involvement of the church in current movements, such as BLM. In a 2021 entry in the “Uplift Memphis, Uplift The Nation: The Blog For Community Engagement,” from the Benjamin L. Hooks Institute for Social Change at the University of Memphis, Johnson wrote that “unlike the Civil Rights movement that it is often compared to, people often do not associate BLM as a faith-inspired movement or one that has anything to do with spirituality.”

“Early in the movement, even some Black pastors lamented the fact that there was a strange silence from the Black church during the Black Lives Matter Movement,” said Johnson.

In his lecture, Johnson explained that his research showed that people used their religion to help them cope with the death of Floyd, and compelled them to get active. He said, however, that many felt they could not solely rely on their religious influences, and that they had to “draw on something else to draw them out to participate.”

He said, “While people of faith have been a part of Black Lives Matter since its inception, some told us that religion played no role in their involvement whatsoever.”

Johnson also quoted respondents who did not identify as religious, and preferred that religion not play a role at all in BLM.

He noted, however, that the Black church had always had a prominent influence on society such as in the Civil Rights Movement, and that the faith that people learn in the church is “one of the primary reasons for their involvement with BLM.”

“For their involvement with BLM, many recognized and realized that it all started in the church that they are, right now, critiquing,” said Johnson. “It was the church that had lost its way, but some of the participants still found a way to join the movement and grounded it in their faith experiences.”

Johnson explained that it not only speaks to the legacy and history of the Black church, but the legacy of activism “birthed from the church that bore witness to the issues germane to African Americans, across a variety of places and spaces, at all times.”