by Jamie Satterfield, Tennessee Lookout

The Tennessee Valley Authority’s coal ash dumps in Memphis rank among the worst in the nation for contamination of groundwater with cancer-causing toxins, according to a new report that relied on the power provider’s own records.

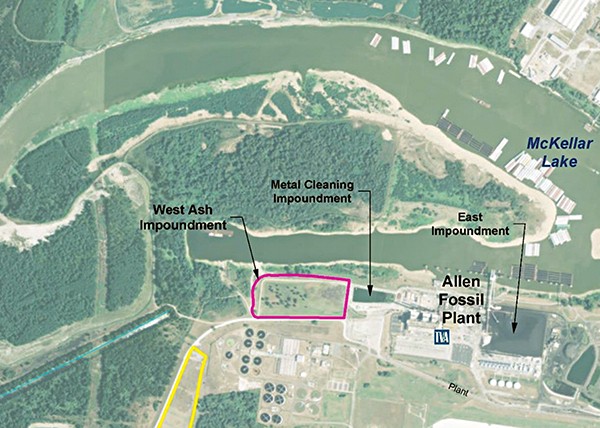

TVA’s coal ash dumps at the now-defunct Allen Fossil Plant rank as the 10th worst contaminated sites in the country in a report released earlier this month that examined groundwater monitoring data from coal-fired plant operators, including TVA.

TVA’s own monitoring data shows its Memphis dumps are leaking arsenic at levels nearly 300 times safe drinking water limits. Unsafe levels of boron, lead and molybdenum are also being recorded there.

The report, prepared and published by the Environmental Integrity Project and Earthjustice, shows that coal ash dumps at every TVA coal-fired facility across Tennessee are leaking dangerous contaminants at unsafe levels, including arsenic, cobalt, lithium, molybedenum, boron, lead and sulfate, into groundwater.

Coal plant owners are ignoring the law and avoiding cleanup because they don’t want to pay for it.

– Lisa Evans, senior ttorney at Earthjustice

TVA, the nation’s largest public power company, was ordered in 2015 to investigate the extent of contamination caused by its coal ash dumps, come up with a plan to clean up its coal ash pollution and decide what to do with the dumps to prevent future contamination.

But the utility still hasn’t completed its investigation at all its Tennessee plants or announced final plans for the millions of tons of coal ash — the byproduct from burning coal to produce electricity — TVA has stashed away in unlined, leaky dirt pits across the state.

The utility is not alone in dallying to comply with the 2015 directive, known as the Environmental Protection Agency’s “coal ash rule,” according to the new report — Poisonous Coverup: The Widespread Failure of the Power Industry to Clean Up Coal Ash Dumps.

“Seven years after the EPA imposed the first federal rules requiring the cleanup of coal ash waste dumps, only about half of the power plants that are contaminating groundwater agree that cleanup is necessary, and 96 percent of these power plants are not proposing any groundwater treatment,” the report stated.

Report: Ongoing contamination in Memphis

According to the report, 91 percent of the 292 coal ash dump sites in the nation are leaking dangerous toxins, heavy metals and radioactive material into groundwater at dangerous levels, “often threatening streams, rivers and drinking water aquifers.”

“In every state where coal is burned, power companies are violating federal health protections,” said Lisa Evans, Senior Attorney at Earthjustice. “Coal plant owners are ignoring the law and avoiding cleanup because they don’t want to pay for it.”

TVA officials responded to the report’s claims in a statement:

“It’s important to note that the Earthjustice report is a flawed document. For example, it does not account for state regulations of coal ash sites that either complement the federal coal ash rule or serve the purpose of applying additional, more stringent oversight over coal ash sites.

“This is the case in Tennessee where TVA is under a commissioner’s order to conduct a thorough environmental study of the sites to help determine the closure method.

“According to the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation (TDEC), Tennessee is the only state in the nation that has all coal-fired power plants under orders to complete investigation and remediation. Tennessee is the only state in the nation to require an electric utility to conduct an environmental investigation and remediation of coal ash disposal locations that include both active permitted coal ash disposal areas, as well as historical coal ash disposal areas.

“TVA is an industry leader in the safe, secure management of coal ash, implementing best practices years before they were required by the 2015 federal coal ash rule and pioneering new technology to ensure our coal ash sites are safe. For example, six years before the federal coal ash rule was enacted, TVA committed to eliminating wet handling of coal ash at all our facilities. The conversion from wet to dry handling is completed.

“TVA’s robust network of more than 450 groundwater monitoring wells ensures the protection of water resources and the environment. Where groundwater monitoring results indicate corrective action is necessary, TVA is following the corrective action process outlined in the federal coal ash rule and applicable state rules.

“Decisions regarding the closure and long-term storage and management of coal ash sites are based on the unique characteristics of each site. In Tennessee, TVA is under a commissioner’s order to conduct a thorough environmental study of the sites to help determine the closure method. Kentucky and Alabama regulators are similarly exercising their oversight through their state regulations. TVA, with oversight from its regulators, will continue to use science, data, and analysis to inform those decisions and each site will be closed in an environmentally safe manner,” concluded the statement.

The coal ash dumps at TVA’s plant in Memphis had been leaking levels of arsenic as high as 300 times safe drinking water standards for years before the utility publicly acknowledged the contamination in 2017.

TVA shut down the Allen plant in 2018 and later announced it would remove 4 million tons of coal ash from leaky dirt pits there and haul it to an above-ground landfill in a black residential neighborhood in south Memphis.

The EIP and Earthjustice report says TVA isn’t doing enough to prevent future contamination at the Allen site. According to the report, TVA “has not posted groundwater monitoring data or otherwise implemented the coal ash rule” at one of the dumps at the Allen plant because the utility “believes the pond is exempt from” the rule.

“We know that TVA has monitored the groundwater pursuant to state law, and that the data show ongoing contamination with high concentrations of boron, molybdenum, and other pollutants,” the report stated.

“TVA should use these data to immediately confirm exceedances in both detection and assessment monitoring and proceed through the coal ash rule’s corrective action process,” the report continued.

Residents in south Memphis have complained that TVA intentionally targeted a Black community when choosing a landfill site and did not allow them a say in its decision.

Dangerous contaminants at unsafe levels

TVA is not required to monitor groundwater contamination for many of the 26 dangerous ingredients in coal ash, so data on the levels of deadly constituents including radium are not publicly available. But of the handful of contaminants TVA is required to track under the coal ash rule, the utility’s Tennessee coal ash dumps are leaking unsafe levels of most of them, the report stated.

TVA’s coal ash dumps at its Gallatin Fossil Plant are polluting groundwater with lithium at 41 times safe limits as well as dangerous levels of arsenic, boron, cobalt and molybdenum. Dumps at that Middle Tennessee plant rank 80th on the list of 292 worst contaminated sites.

Dumps at TVA’s Kingston Fossil Plant in Roane County — the site of the nation’s largest coal ash waste spill in 2008 and the impetus behind the enactment of the federal coal ash rule — are leaking arsenic at levels 16 times higher than safe drinking water limits, the report stated. Dumps there are also leaking cobalt at levels 20 times safe standards, lithium at 10 times safe standards and molybdenum at five times safe standards. Kingston ranks 82nd on the list of worst contaminated sites.

Coal ash dumps at TVA’s Bull Run Fossil Plant in Anderson County are contaminating groundwater with lithium at a rate of 13 times the safe standard, arsenic at a rate of seven times the safe standard, boron at nine times the safe standard and molybdenum at five times the safe standard, according to the report. Bull Run’s dumps rank 101 on the list.

TVA’s coal ash dumps at its Cumberland Fossil Plant in Stewart County, Tenn., rank 115th on the list, leaking boron at 22 times safe levels, as well as unsafe levels of arsenic, cobalt, lithium and molybdenum, the report showed.

Dumps at TVA’s Johnsonville Fossil Plant in Humphreys County, Tenn., are leaking cobalt at nine times safe levels and boron at four times safe levels, according to the report. Coal ash pits at its long-shuttered John Sevier plant in Hawkins County, Tenn., are leaking lithium at unsafe levels, the report stated.

Tennessee Lookout is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Tennessee Lookout maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Holly McCall for questions: info@tennesseelookout.com. Follow Tennessee Lookout on Facebook and Twitter.

Southern Environmental Law Center

Southern Environmental Law Center  TVA

TVA  TVA

TVA  Southern Environmental Law Center

Southern Environmental Law Center  Southern Environmental Law Center

Southern Environmental Law Center  USGS

USGS

Tennessee Valley Authority

Tennessee Valley Authority