Al Kapone wrote “COVID Blues” and “Hustle Up” shortly after the quarantine began a few months ago. But as time progressed, Kapone, 48, wasn’t sure the songs would fit his new album, Hip Hop Blues, which he will release June 24th.

“I wrote those while we were really in the thick of it,” Kapone says. “I’d say mid-May. I wrote them based on what was going on from the time it hit to that point. A lot has evolved since then. In a way, those songs are dated. They’re not as current as where we are now.”

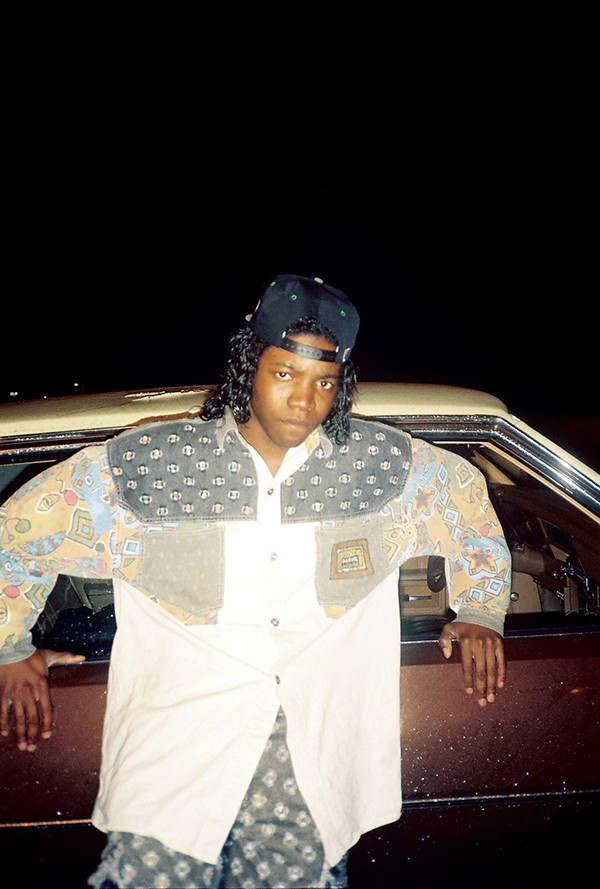

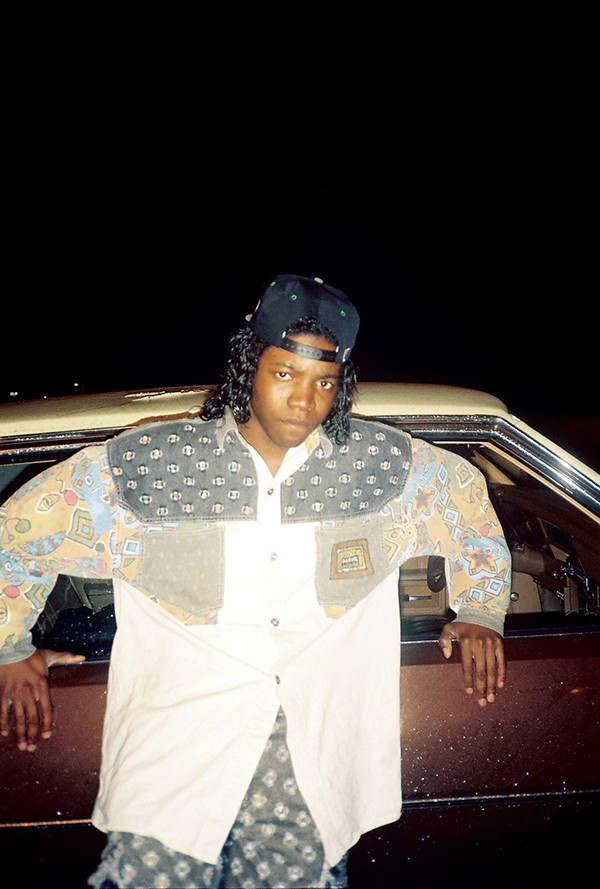

Photographs courtesy of Al Kapone

Photographs courtesy of Al Kapone

Both songs — which didn’t make the cut but are slated to be used in upcoming films — are “basically talking about when it literally started taking off. About how one moment we were hearing about it overseas and the next moment, ‘Holy shit! It’s coming to us. It’s here.’ And it happened so fast nobody was really ready.”

The message in both songs is, “Through it all, we gotta hustle our way back into society. Fight the pandemic. Get finances together. We’re going through all this. We got to fight back.”

But, he says, “After I wrote those two songs I started revisiting some of the blues hip-hop songs I’d already done.”

“Blues hip-hop” is a song with “super heavy blues guitar rhythms.” But it can be diverse. It could be “blues hip-hop” or “rock hip-hop,” he says. “I like all styles of music. I tend to create different styles of music through hip-hop.”

Among the songs on the new album are “Drunk as a Skunk” — about “getting drunk as hell” — that he wrote with Cody Dickinson of the North Mississippi All-Stars.

“Rock Me Baby” is a remake of the Melissa Etheridge song. “She had given me the blessing to use it. And with Uriah Mitchell, we reworked it and made sure it had that hip-hop feel.”

“Dead and Gone,” a collaboration with Eric Gales, is “basically saying you need to right your wrongs before you’re dead and gone.”

Photographs courtesy of Al Kapone

Photographs courtesy of Al Kapone

Al Kapone, Craig Brewer circa $5 Cover

During his long career, Kapone has written more than 1,000 songs, including, “Whoop That Trick,” which was in the Oscar-winning soundtrack of the 2005 made-in-Memphis movie, Hustle & Flow, directed by Craig Brewer.

He’s using “AK Bailey” as his name on the album. “With the blues project, I’m trying to carve out a different brand.” Kapone, whose real name is “Al Bailey,” is going back to his roots, in a way.

Music was his first creative expression, says Kapone, who was born in Memphis. “My grandmama and mama said it came in when I was a kid, before I even remember. When I was 2 years old, I’d say I was doing James Brown moves and singing songs like ‘Shoeshine Boy’ by Eddie Kendricks.”

Kapone moved with his mom to Bakersfield, California, when he was in the third grade. That’s where he began writing — but it wasn’t songs: “The elementary school I went to encouraged us to write a story. They said, ‘You can write whatever story you want to write.’ I remember writing this story. Something about being in the ocean. Something about a fish. It was something crazy, but I got really into the story and it hit me then that I was into characters.”

About a year and a half later, Kapone moved back to Memphis, where he joined the newspaper staff at Lauderdale Elementary. “I was into the school newspaper. And I started learning more about the craft of writing. I was a little reporter and didn’t realize it. I was into story writing, just telling the story. Just a cool story people can read and get caught up in.”

Kapone later translated the basics of writing a news story to performing. “When I’m on stage, it’s a story. ‘Cause you got the beginning — it has to grab you. Then you got to take the audience into the journey in the middle. And it has to end with the right ending.”

He began performing in funk groups when he was in the fourth grade. “We used to have these little dance groups. You’d be out in your front yard. Once you get the routine down, you’d perform it in the neighborhood. People were so happy to see these little kids doing these dance routines.”

Later, Kapone was impressed with some provocative dance groups. “They were always men. They’d do all the provocative moves and the women would scream. I’d watch them: ‘Man, I want to do that.’ But I didn’t know how to dance.

“By the time I got into hip-hop, it wasn’t just being a rapper or getting on stage with a mic and rapping, walking back and forth and rapping, you’ve got to put on a performance. That’s always been part of my makeup.”

Kapone was introduced to hip-hop through the music of LL Cool J and Run-D.M.C. “I knew hip-hop was the right thing for me ’cause I couldn’t sing. I always wanted to perform, but I can’t sing. So hip-hop was like, ‘Oh, shit. I can do this. I can be an artist because it’s not about singing. It’s about telling cool stories and the rhymes. I could tell cool stories and I could perform them. I could do this in rhythm and rhyme.'”

And, he says, “I fell in love with the culture. The breakdancing. The deejaying. Graffiti. The way hip-hop people dress. I was into all of that. I was engulfed in the hip-hop culture. If it wasn’t for hip-hop, I’d probably never have been a performer.”

He joined the Peewee Emcees when he was in the sixth grade. “We all delivered groceries at Lauderdale Sundry. That was the first time I officially became a rapper.”

In junior high, Kapone joined a rap group called Jam Inc. Leno Reyes, a former drummer for Rick James who had moved from New York to Memphis and started a funk group, “kind of took us under his wings.”

Reyes gave them a valuable piece of advice: “You go on stage, you are controlling the crowd.”

“He said it in a way where I really felt it. It was like he translated power to me when he said it. ‘When you go on the stage, you are the master.’ And it felt so powerful that whenever I went on stage from that point I knew I’m in control. I’m the master.

“I don’t need the audience to give me the energy. I give them the energy. I’m going to take the audience on a journey with me. And my goal is to outperform anybody that’s going to perform that day.

“I built up my name. I’d go up on stage and perform almost like a rock star. And that resonated with the audience.”

He was “one of the first rappers to perform in rock venues” at the age of 16. “Even though I was hip-hop, I had that rock star mentality.”

Kapone joined a group called Men of the Hour, which performed with “other up-and-coming rappers,” including DJ Spanish Fly and 8Ball & MJG, at the 21st Century Youth Club.

They recorded at OTS Records in Orange Mound. “That’s where Gangsta Pat had blown up. Me and 8Ball would record songs trying to outdo each other. We were developing the Memphis rap sound at that time. That was the genesis of it.”

Photographs courtesy of Al Kapone

Photographs courtesy of Al Kapone

“Lyrical Drive By” days

Kapone became a solo artist after Men of the Hour broke up. “That’s where I literally became Al Kapone, and everybody knew who I was ’cause I had this song, ‘Lyrical Drive By,’ which blew up in Memphis and regionally. I was doing shows in Memphis, Mississippi, Arkansas, and experiencing the real fans.”

But, he says, “To this day, I never really wanted to be a solo artist.”

That’s when he said, “I need a cool solo rap name.”

He was watching the 1932 movie, Scarface, based on mobster Al Capone. “I said, ‘That’s my name.’ It just grabbed my attention. That name is the shit. My name is Al anyway.”

Kapone went by Scarface Al until he discovered the Ghetto Boys had a group member named Scarface.

So, he became Al Kapone, but he says, “Of course, Al Capone is associated with gangsters, the whole gangster world. At some point I’m still just a songwriter, a guy from the projects and the hood.”

Kapone says now that he didn’t want to be pigeonholed into just writing gangsta songs. “I wanted to write different types of songs. Not just stuff that goes on in the streets, in the hood. I’m a writer. I can write about anything.

“I used to piss audiences off. My songs had nothing to do with being a gangsta on the street. It was human life struggles. Black struggle shit.

“People were like, ‘I want to hear “Drive By,” dammit, and you’re talking about struggling as a black man. What the fuck. I want to hear some shooting and stuff. You’re talking about trying to better yourself.’ That name got in the way.”

But, he says, “I could never come up with anything. I was already known at this point.”

Kapone had been an independent performer for 14 years and says he had become “stagnant” when Hustle & Flow came along. “When Craig gave me the opportunity to do my music, and once they accepted me and the movie came out and blew up and everybody talked about the music in the movie, it gave me a whole other level of attention.”

Hustle & Flow put Kapone “in a situation to write more songs for other artists. Writing songs for different movies. And labels were calling me for a lot of songwriting and stuff like that, but at some point it became like an assembly line. It’s not fun anymore. It becomes robotic. And I was like, ‘This is not how you write songs.’ You write songs from a feeling of creativity. Not someone throwing you something and saying, ‘Write. Write. Write.’ I kind of shied away from the music business for a while ’cause I wasn’t feeling like that.”

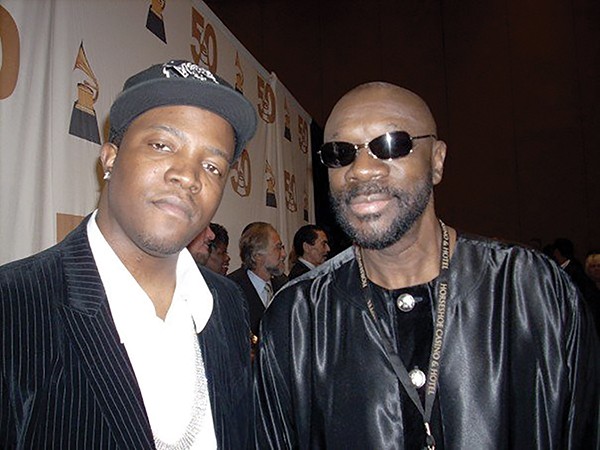

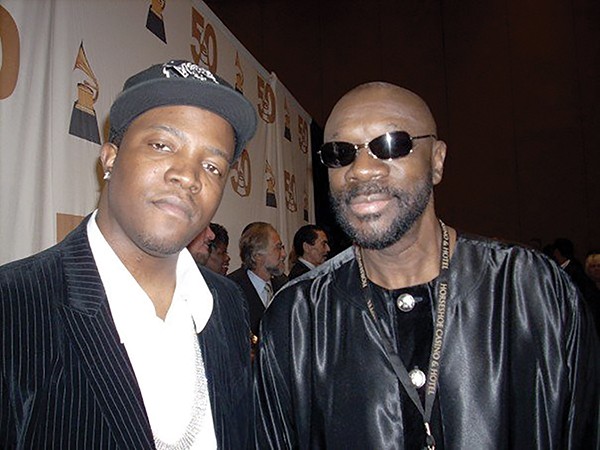

Photographs courtesy of Al Kapone

Photographs courtesy of Al Kapone

Eric Gales (left) collaborated with Al Kapone on “Dead and Gone.”

But, he says, “When I stopped being a part of the music business, I started listening to music as a fan again. The same way I did when I was in elementary school when I became a fan.”

Kapone knew he wasn’t going to quit show business. That “reassured me to not leave it. ‘Cause I felt the good feeling I felt from being creative again.

“I’m blessed with a level of creativity and blessed with being able to express it. And blessed to put it out when it feels good to me. Not because I have to.”

During the quarantine, Kapone discovered that a video made by Running Pony using his rendition of “Eye of the Tiger” had won the No. 1 intro in the country by National Association of Collegiate Directors of Marketing (NACMA). He recorded it with the University of Memphis’ Mighty Sounds of the South band at Royal Studios. “Uriah Mitchell did vocals with me, and we made it happen.”

Photographs courtesy of Al Kapone

Photographs courtesy of Al Kapone

Al Kapone (left) and Isaac Hayes

The win was “a ray of light in a way,” he says. “It gave everybody a sense of pride when they heard about that news. I feel that pride was much-needed, especially in Memphis, going through what we’re going through. It lifted a lot of people’s spirits. Memphis — we’re still out here making noise in spite of everything. Know what I’m saying? We’re David beating Goliath still.”

Royal Studios owner Lawrence “Boo” Mitchell says Kapone “always manages to stay current throughout his creative process.”

He stays relevant, “pushing himself as an artist and doing something cutting-edge that nobody else has done before.”

Stax co-owner/record producer and songwriter Al Bell says Kapone is “very aware of the shoulders on which he stands: the veteran Memphis musicians from Stax Records, Hi Records, and others who helped create ‘The Memphis Sound.’ Those musical roots are very important to him, and I think that’s one of the factors that make his style so entertaining.”

And, Bell says, Kapone “has proven that he can move from the underground status younger audiences tend to follow, to more mainstream works that often tend to celebrate Memphis in various ways. He was born in Memphis, lives in Memphis, and loves Memphis. Al is Memphis.”

To hear Hip Hop Blues, go to akmemphis.com.

Photographs courtesy of Al Kapone

Photographs courtesy of Al Kapone  Photographs courtesy of Al Kapone

Photographs courtesy of Al Kapone  Photographs courtesy of Al Kapone

Photographs courtesy of Al Kapone  Photographs courtesy of Al Kapone

Photographs courtesy of Al Kapone  Photographs courtesy of Al Kapone

Photographs courtesy of Al Kapone