The most insightful film I’ve ever seen about Elvis Presley is “The Singing Canary,” a five-minute experimental short by Memphis director Adam Remsen. It contains neither images of Elvis nor his music, only footage of astronauts and rocket launches. Remsen’s voice-over casts Elvis not as a singer or entertainer or idol, but as an explorer of new psychic spaces.

Yes, Elvis was supremely talented, superhumanly good looking, and unbelievably charismatic. But it was sheer luck that he came along at exactly the moment in history when a combination of rhythm and blues, amphetamines, and television could transform a penniless truck driver into the most famous person who had ever lived. “No one had ever been in his position before. He did the best he could,” said Remsen. “He was just living his life, making the best choices he could. As it happened, he was unprepared to make those choices, in one way or another.”

Who could have been prepared? The only people who had been as famous as Elvis circa 1957 were pharaohs. A decade later, The Beatles would express relief that, when they were thrown into the maelstrom of modern fame, at least they had one another. Elvis was alone, going through stuff no one in the entire 300,000-year history of Homo sapiens had ever gone through before. “He was the singing canary we sent into the gold mine. And when the singing stopped, we learned it was dangerous in there.”

The latest big screen attempt to tell The King’s story shares this view of Elvis as a martyr for the information age. Baz Luhrmann is one of a handful of directors with an instantly recognizable style. As technically exacting as he is bombastic, Luhrmann’s films are the closest thing we have to the lavish MGM musicals of Old Hollywood. Emotions are heightened, the cutting is frenetic, and realism is an afterthought. Music and montage are Luhrmann’s love language, and everything else is in service of maintaining the momentum. When he’s on his game, Luhrmann can sweep you up and transport you to another place like the tornado in The Wizard of Oz.

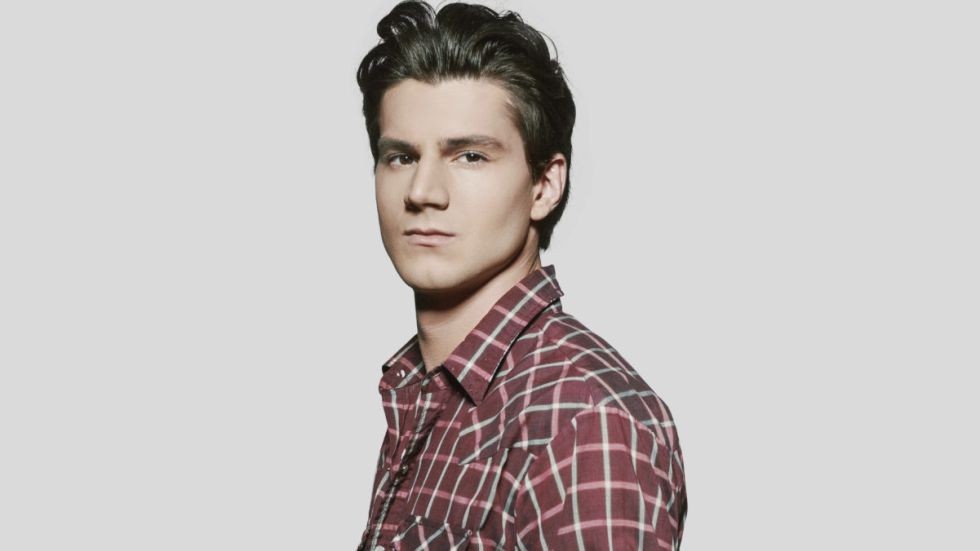

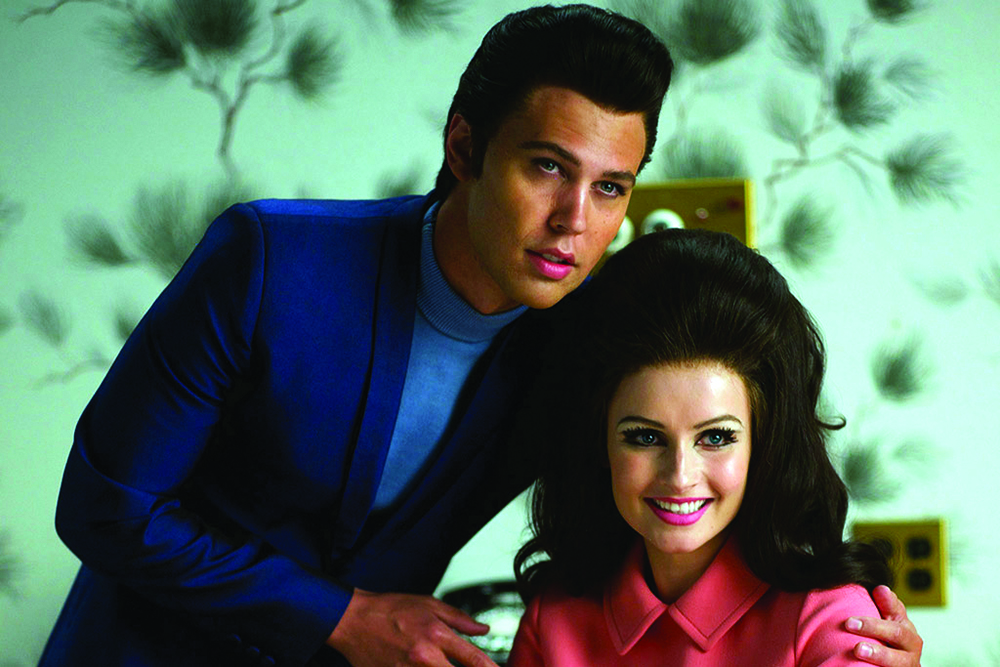

This film rises above the simple jukebox musical I feared we would get when I heard Luhrmann was taking on the story of The King. Credit for much of its success must go to Austin Butler, who has the unenviable task of trying to bring to life the most impersonated man in history. On the Louisiana Hayride and at the triumphant July 4, 1956, Russwood Park homecoming show, Butler is electrifying. He’s got the cheekbones, and he knows how to use them.

The racial politics of the era are never far from the surface. In Luhrmann’s vision, Elvis’ smoking-hot sexuality was what made him dangerous. But what scared The Establishment about this poor white kid singing Black music was not how he danced — it was that Elvis represented a crack in the South’s Jim Crow apartheid. He didn’t just laugh at the minstrel show; he identified with B.B. King, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, and Little Richard. Some of the white kids who followed him would go on to discover The Bar-Kays, Sam Cooke, and Aretha Franklin, and begin to think, “Hey, maybe these Black people are humans, just like me.”

But the protean summer of ’56, which has for so long formed the fetish of rock-and-roll, doesn’t interest Luhrmann as much as the Vegas era. It begins with an elaborate staging of the ’68 Comeback Special. Instead of focusing on the in-the-round jam session, which remains one of the greatest live musical performances ever put before a camera, Luhrmann finds meaning in Elvis’ selection of “If I Can Dream” as his closing number. Butler delivers the moment with maximum gravitas.

Luhrmann’s most polarizing decision is to tell the story from Col. Tom Parker’s perspective — and not just because of Tom Hanks’ accent. Having the villain as the narrator is a very Shakespearean choice, intended to make Parker into Iago, a malignant influence confiding to us about the lies he’s whispering in the hero’s ear. Parker was the consummate confidence man and a natural-born carny barker. In the early days, he and Elvis were an unstoppable team. When Elvis was languishing in Vegas, it would have been better if he were alone. Parker gets the blame for Elvis sitting out the Civil Rights fights of the late ’60s and for missing opportunities to tour the world. He gets credit for the groundbreaking Aloha from Hawaii concert, the definitive document of Elvis’ late period. But Luhrmann declines to use the first satellite broadcast to a global audience of one billion as a climax, like Queen at Live Aid in Bohemian Rhapsody. As for Hanks’ performance as the shady Dutch immigrant, let’s just say that the veteran actor knows when to put the ham on the sandwich.

The standouts in the sprawling supporting cast include Helen Thomson’s sad turn as the alcoholic Gladys and Olivia DeJonge’s uncanny Priscilla. The Power of the Dog’s Kodi Smit-McPhee gets a standout cameo as Jimmie Rodgers Snow, one of the first people to understand the depth of Elvis’ power. During the early film’s frequent digressions into the Beale Street music scene, Yola Quartey and Shonka Dukureh each get show-stopping moments as Sister Rosetta Tharpe and Big Mama Thornton.

Ultimately, your reaction to Elvis is going to depend on whether or not you can vibrate on Luhrmann’s frequency. I was a fan of the director’s early work, like Romeo + Juliet, but found The Great Gatsby off-putting and snoozed through Australia. Elvis is a return to the explosive Luhrmann of Moulin Rouge. He freely twists the songs, sometimes in ways that are insightful, and sometimes in ways that betray a lack of trust in the material, like using anachronistic hip-hop beats whenever we return to Beale. The film is massively overstuffed with striking images, but that kind of sounds like complaining because you have too many scoops of delicious ice cream. It’s understandable if you find the constant barrage of visual information disorienting or the constant dance on the edge of camp cloying. But when Elvis is on stage, and Luhrmann is on fire, you understand why The King will live forever.