The facade of the New Chicago Community Development Corporation (NCCDC) could be described as forgettable. A two-story, manila-brick building on a sleepy street in its namesake community, there isn’t a particular feature of note, except for the five-pound guard Chihuahua that will suspiciously eye you as you approach the door.

Carnita Atwater, the building’s owner and operator, prefers the unremarkable exterior. “I like to catch people off guard, y’know? That way they have no idea what they’re walking into.”

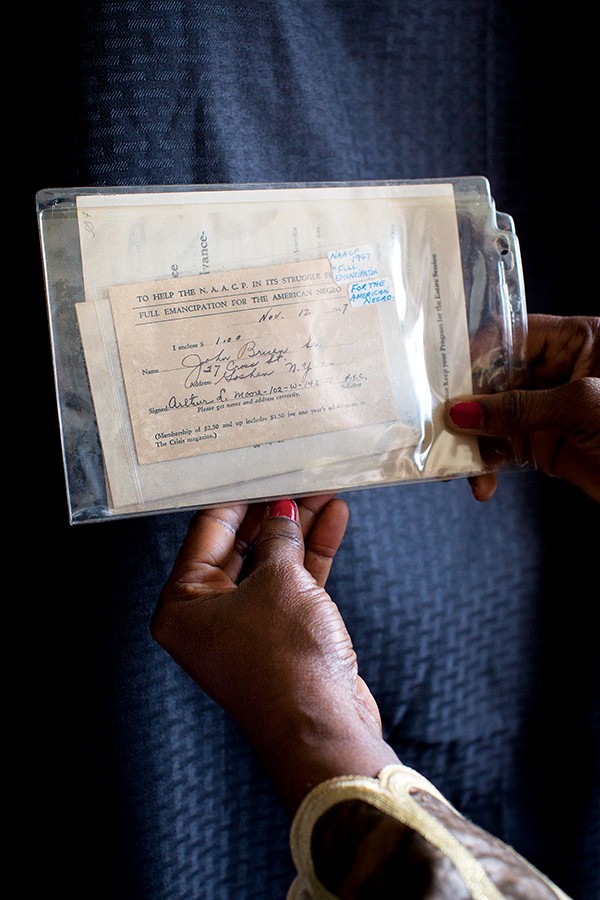

What people are walking into is the very tip of Atwater’s artifact iceberg, amassed over 30 years from around the nation and beyond, and carefully arranged in a nondescript building that serves as half-museum, half-community center.

The first-floor museum in the NCCDC contains a small slice of Atwater’s collection. Dozens of stacked rubbermaid containers stored on the second floor contain a little bit more. And beyond the walls of the NCCDC, dozens of storage units contain the rest.

Atwater estimates that in order to fully display everything she has collected, the NCCDC building would need to sprout seven more stories.

The front hall is flanked by lavishly framed portraits of recognizable figures in America’s Black history: Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., Frederick Douglass (it turns out he’s been deceased for a while, who knew?). There’s a sarcophagus replica (one of just a couple of replicas for aesthetic purposes) just beyond the sign-in desk. It’s a hint that this story will go back to the beginning.

The display cases running along the cinder-block walls contain hand-painted wooden letters spelling out each case’s theme: “Negro Spirituals” for the case filled with 19th-century sheet music; “Hateful Shame” for the case containing rusted shackles that once clasped Black wrists.

Carnita Atwater’s New Chicago Community Development Corporation showcases Black history.

Each wing of the museum testifies to the existence and humanity of well-known and unknown Black Americans. No one necessarily knows who Tom Meriwether was, but you will know — at least for the time you are in the museum — that he graduated from grammar school in the late 1920s from Memphis City Schools. You can see his certificate, scrawled out in elaborate cursive just a few tables down from first-run Memphis Minnie vinyl records.

Though Atwater’s museum lacks the resources that its downtown counterpart, the National Civil Rights Museum has, there’s no shortage of appreciation from the surrounding community it serves, because the NCCDC has a two-fold existence, and the other part of it is dedicated to serving and uplifting the New Chicago area.

Beyond the main wing and behind gold satin drapes is a spacious dining hall, which can be converted for weddings or community meetings at a moment’s notice. Frequently, community meals for the neighborhood are hosted, free of charge.

In the hall, plush purple velvet chairs are waiting for the kings and queens of the day. Silver tureens are polished and at the ready to host heaps of spaghetti and pulled pork. The details are meant to remind the community it serves of the royalty in their bloodlines and that whoever walks in for a meal will always be treated with the dignity that the room commands, regardless of status.

For organizations and families that can afford it, Atwater will rent out the hall for a modest $600. For those who can’t afford it, Atwater finds a compromise. No one is turned away.

Welcome to New Chicago

Initially, Atwater was aiming to place her museum in the heart of downtown. She notes with a raised eyebrow that she tried to buy Clayborn Temple a few years back, but was turned down. She also tried to acquire the old police station on Adams but was unsuccessful.

“Then I went Harriet Tubman underground on them,” Atwater says.

In 2003, she purchased the two-story building now housing the NCCDC and set to work transforming it into a community hub. Though it would be over a decade later before the museum portion of the NCCDC would officially open, it was always part of the goal.

“I said, ‘Okay then, I’m going to take my museum and place it smack dab in the middle of the ghetto. I’m going to get tourists over here to New Chicago.'”

It might not have been the original plan, but Atwater has leaned into the New Chicago community, and constantly schemes about how she can catalyze its development.

Though her doctorate is in public health, Atwater has a lengthy record of owning and operating businesses. She opened her first business at 12, after her father bought her a new John Deere lawn mower. After each new lawn-care customer in her hometown of Clarksdale, Mississippi, was secured, she would present them with a handwritten contract that bound them to a certain length of service.

Her business instincts have only sharpened since, and they are currently laser-focused on New Chicago.

The area, once home to the long-shuttered Firestone Rubber & Tire Company, is undeniably economically depressed, as most majority-Black neighborhoods in Memphis are. For the past few decades, the community has been steadily bleeding out. According to Shelby County data, property values have been in free-fall — dropping by as much as 36 percent between 2004 and 2014. Public transit routes have been cut, and consequently, jobs began to follow.

Half of New Chicago resides in a census tract where more than 46 percent of the jobs are defined as low- or moderate-income, and 23 percent of the community is unemployed. The median income hovers between $19,000 and $22,000 a year.

One block west of the NCCDC is the vacant land parcel where Firestone once thrived. Only the smokestack remains on the 71 acres. Atwater wants the land for development purposes.

“I asked them if they would consider selling me that property, and from what I understand, they are wanting to bring in a manufacturing company,” she says. “But, they don’t have a contract yet, and so that’s fair game.”

For now, it seems as though Atwater might face another rejected attempt to secure a parcel in which she sees potential. This frustrates her.

“That’s just part of the make-up from the city of Memphis. If you’re not in with the clique, then you’re out,” says Atwater, adding that she doesn’t plan on starting to force her way in at this point in her life.

“My concern has never been to get in with the right crowd; my concern has always been taking care of the people,” she says. “At this point in 2017, we should be about the business of taking care of the people. I’m trying to bring culture and economic development back in this community. Why not help someone like me, who has been helping this community for years?”

Facing History

The driving force behind Atwater’s museum boils down to one belief: “We haven’t taught our history,” she says.

Atwater argues that schools — Shelby County Schools in particular — do not teach Black history in its entirety. She also poses the thought that parents have a hand in what she views as a “softening” of history.

“What do I mean by that? Look around. It’s Black History Month in Memphis, Tennessee, and it’s like a ghost town. You aren’t hearing anything about events or commemorations on TV. You’re not reading about it much in the news. So here we go again, committing the same sins of the past. Once you do not acknowledge the African-American people, then you make them obsolete.”

Atwater was introduced to Black history at an early age by community elders. She admits that her education from the mouths of elders was critical and forming, but not as explicit as it needed to be.

“They didn’t tell me about the lynchings, they didn’t tell me about the rapes, and they didn’t tell me about the amount of hatred placed upon African Americans,” she says. “I think, in a way, they wanted to preserve my innocence as a child.”

Spiked collars depict the trauma of the Black experience, a history Atwater refuses to shy away from.

While Atwater understands the impulse to preserve innocence, she is also adamant that the lack of a complete history has gone hand-in-hand with a lack of humanization when it comes to being Black in the U.S. today.

That’s why one of the very first things you will see in her museum is a display case showcasing shackles and spiked collars. It’s why sculptures and portraits throughout the museum depict, in near equal measure, both the pride and the trauma of the Black experience.

“I have to give the Jewish communities credit, because they teach their children the complete history of their people at a very early age,” she notes. “That’s what missing in the African-American community and in the United States. How are we going to rectify this? There’s no simple answer. But you cannot tell the history of the African American without talking about the suffering.”

Much of Atwater’s museum is unapologetically dedicated to suffering, but a lot it is dedicated to contributions as well. The balance sums up her philosophy of teaching history in its entirety.

Repeating History

Atwater has been asked to describe what freedom looks like to her on multiple occasions. Her answer is multi-pronged: “You have the right to live in decent housing. You have the right to have decent transportation. You have the right to have food every day. That’s freedom to me. That’s basic,” she says.

In her view, Black Americans — in Memphis at least — are not yet free. “We spent $250 million on Bass Pro, and right down the street in North Memphis, you have senior citizens barely keeping up with their taxes and eating cat food, because that’s all they have. That’s not equality, and this life in Memphis is no joke.”

Atwater recognizes that she alone cannot solve inequality in Memphis. Martin Luther King Jr. once famously warned about the dangers of the white moderate and how silence about injustice serves to perpetuate it. Though Atwater doesn’t assign the inaction King spoke of solely to the white population of Memphis, she is concerned about the multitude of people in positions of power who choose to ignore Memphis’ worst economic inequalities.

She asserts that “certain people believe in going along to get along.” In her view, the remedy to the silence is to keep making the conversation uncomfortable. And, standing in Atwater’s museum, surrounded by bullwhips and chains that once tore into flesh, can easily make you uncomfortable.

It’s what she’ll keep pushing for.