Artist Nelson Gutierrez was born in Colombia and worked in various places around the world and in the United States before coming to Memphis six years ago. But you’ll be hard-pressed to find anyone as devoted to local artists and art.

Gutierrez has an exhibition opening this weekend at 2021 Projects, a gallery at 55 South Main Street. That space is not the usual art venue, however, and that’s due to the artist working with the Downtown Memphis Commission (DMC) and numerous other artists in town to make it an attraction on several levels.

That otherwise vacant space is part of the Open on Main retail initiative, a project that goes to the heart of the DMC’s mission to boost the economic presence of Downtown. There are, as any who stroll along Main Street will attest, plenty of empty storefronts. Open on Main makes it possible for entrepreneurs, artists, and small business owners to take a low-risk chance on testing their concepts Downtown in some of these storefronts.

Open on Main

Brett Roler, vice president of planning for the DMC, says, “Blight and vacancy drag down property values, curtail a vibrant street life, and make it harder for our existing businesses to thrive.” It is clearly better to have open doors and engaged pedestrians. The program has helped more than 30 store operators test the retail market Downtown, with more than 80 percent participation by minority/women-owned business enterprises.

Open on Main typically provides rent-free opportunities for tenants to have their pop-up businesses on Main Street. The arrangement is usually for a month, but Gutierrez was able to secure a six-month plan since he was having rotating exhibitions of about a month each. His stewardship began in January and has gone well enough that the DMC has agreed to let him continue using the space through December.

“What they’re doing is letting entrepreneurs use the empty spaces temporarily in order to test businesses,” Gutierrez says. “It’s not specifically for art, but as that’s my field, I said that that would be a good thing to do.”

He was talking with the DMC last October when so much was still closed to public activity, but they realized it was the time to start looking at ways to reactivate the art scene. “I knew there were going to be a lot of obstacles and limitations due to the pandemic, but we had the tools to do a lot of things virtually. It wasn’t just the exhibitions or the physical space, but also the social media that we would promote, and the interviews we’d do, and promoting the website.”

Gutierrez got together with artist Carl Moore and discussed who could be part of 2021 Projects. “We wanted to help the artists that are not represented by a commercial gallery, so that was our main criterion,” Gutierrez said. “Carl has been here for a very long time, so he knows more people than I do after only six years that I’ve been in the city. We made a list of people that would be able to participate. Another criterion was the quality of the work, so those people had more need to find spaces to execute their work or to reach the public.”

Artists who have exhibited so far are Andrea Morales and Khara Woods (February-March), Maritza Dávila and Carl Moore (March-April), and Johana Moscoso and Scott Carter (May). Gutierrez’s retrospective show runs from Friday, June 4th, through Friday, June 25th.

Portrait of the Artist

Gutierrez’s work is very much grounded in his experiences in Colombia, which have been, he says, in a type of civil asymmetrical war among the Colombian government, left-wing communist guerrillas, right-wing paramilitary groups, and the drug cartels.

“It’s a really complex conflict,” Gutierrez says. “And I grew up in the middle of that. The government was fighting to provide order and stability. The guerrillas claimed to be fighting to provide social justice. The paramilitary groups were reacting to threats by guerrilla movements and to protect private interests. The drug cartels were fighting to protect their own businesses. And basically the people that most suffered were the civilians at large.”

He says most fighting was happening in remote rural areas in mountains and jungles. “There were several cases of terrorist attacks in big cities, which increased in the mid-’80s to the early ’90s. I was affected directly by that violence. Everybody in Colombia knows someone that at some point was kidnapped. Everybody in Colombia knows someone that at some point was badly hurt or killed by these types of situations. So that was our reality.”

In the late 1990s, Gutierrez left his homeland and went to England to study for his master’s degree. It was transformative. “When I started seeing the whole thing from outside, everything changed because when I was living in Colombia, I was used to it,” he says. “That was what we were seeing every single day in the news. We didn’t even have a sense of shock anymore. That’s not normal.”

He started to do some work on the subject of kidnapping. “There were about 1,500 people kidnapped,” he says, “so the work is about that and the spaces where people are kidnapped and how families suffer — all the psychological impacts of these particular crimes in a society.”

And there were the land mines. Gutierrez says more than 11,000 people were killed or wounded by land mines in Colombia. While in England, he did an installation for UNICEF and the Colombian Embassy regarding that. Despite a 1997 Mine Ban Treaty, the United States, along with China, India, Pakistan, and Russia, have not signed the treaty. Colombia, however, did sign it.

The Road to Memphis

After his master’s degree, Gutierrez went back to Colombia to teach for a couple of years, and he met his wife. They moved to Miami where he worked for an educational foundation. After four years there, he went to Washington, D.C., for eight years, continuing to do his art and to teach. His wife worked with nonprofits, including United Way International, until she received an offer from the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC), the fundraising organization for St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital.

And that’s how they came to Memphis.

He got an offer to work with ArtsMemphis as an artist advisory council member in 2016. “I was helping to understand better the situation of diversity in the city and in the county and how we could impact, in a more balanced way, the artists in the city based on that,” he says. In those years, he met artists and did work with the UrbanArt Commission. One of those artists he met was Carl Moore, who told Gutierrez about the program.

Being able to secure 2021 Projects for an additional six months was a definite win for Gutierrez. “When we first made the list of artists, the list was really extensive,” he says. “It’s not just the people that we’re showing now — there are a lot more people that we would like to support and show their work.”

Sorting Through His Passions

As for his own work, he continues to address the issues in his home country. “Having lived that conflict from inside and then seeing it from outside and seeing it now after 20 years, how do I feel about that?” he wonders. “I don’t feel like I’m a hundred percent Colombian anymore — it’s not that I’m not Colombian, but I don’t feel as I used to feel before. Things have changed, and I have changed. I’m trying to understand that and understand the history of the country and understand that as an outsider-insider. I don’t know — is that like a weird situation of non-place?”

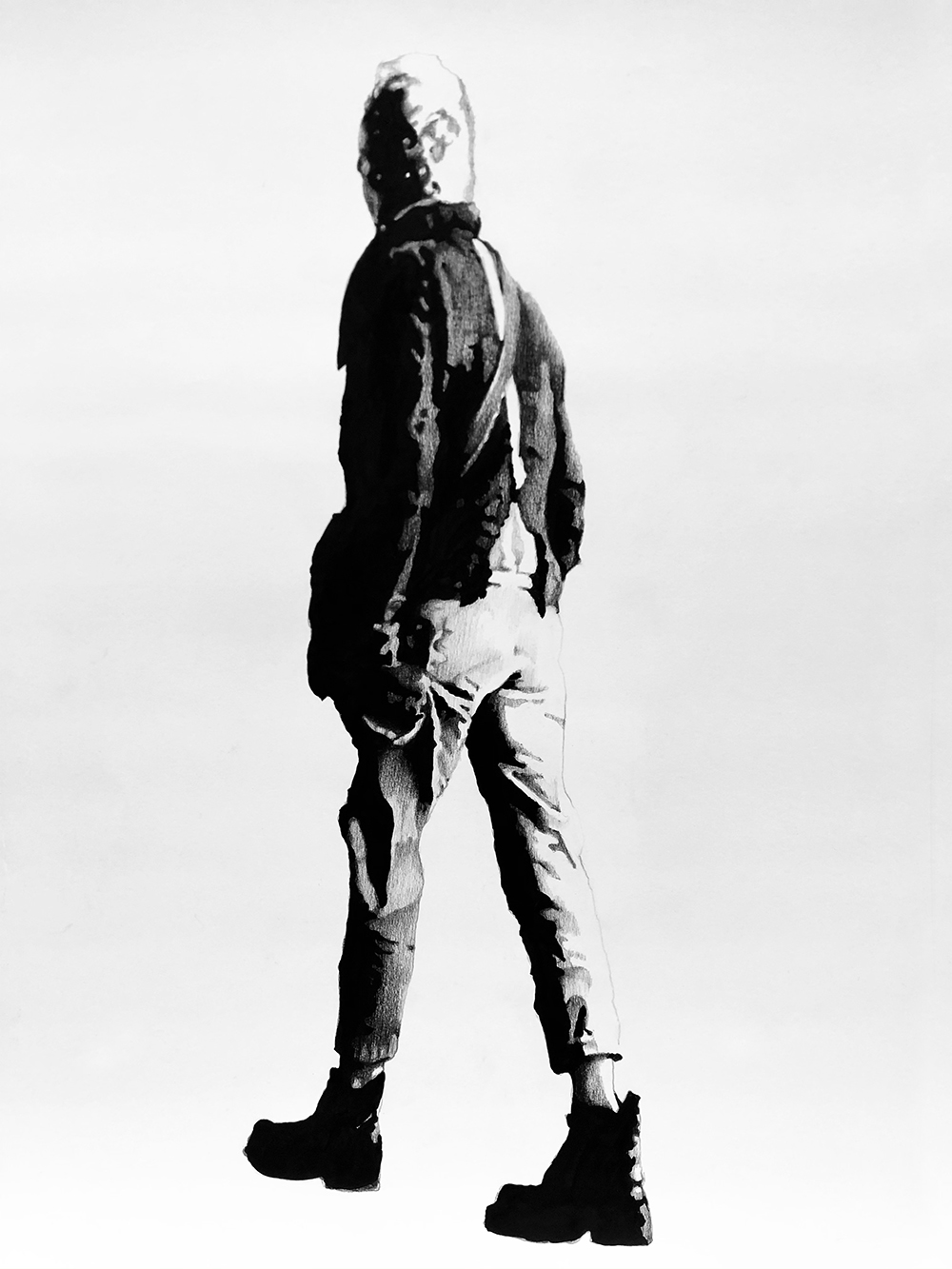

These are the musings of an artist sorting through his passions. But it is what artists do, and Gutierrez is not idling. “Some of the work that I’m doing now, some of the drawings that I’ve been working on are based on photographs from the 1940s and 1950s,” he says.

Some of those photographs were taken on April 9, 1948. A political assassination that day sparked violent riots that came to be known as “El Bogotazo.” It changed history.

“That started the violence that we’re living in now,” Gutierrez says. “So that’s what I am working on now. And how am I seeing that from the outside 75 years later? Even after 75 years, you see repercussions of those acts.”

Whatever questions he still has, Gutierrez knows this about his art: “The intention of the work is to point to this reality and to engage people in a critical debate around it changing in the public their habitual way of looking and thinking, in an effort to create empathy again.”

Another view comes from Marina Pacini, who was chief curator at the Memphis Brooks Museum of Art from 2001 to 2019. Speaking of a recent series, she says, “Like his earlier works, the images are a graphic exploration of human interconnections, and they emphatically demand close attention from viewers, who are rewarded for their effort. With a simplicity of means, Gutierrez packs both a literal and a metaphorical punch.”