As you survey the bounty of your Thanksgiving Day dinner this year, send up a word of thanks to the honeybee. From your Aunt Delia’s pecan pie to Nana’s cranberry-orange relish and that heavenly sweet potato casserole, all those fruits and nuts and vegetables are made possible as the result of pollination from bees. You may not realize it, but honeybees — European honeybees to be precise — pollinate about 80 percent of the foods we eat.

In fact, bees are so important that Mike Studer, the state apiarist who inspects registered hives in Tennessee for disease and pests, routinely fields phone calls from farmers requesting bee colonies to help with their crops. A rancher in Middle Tennessee told Studer his cattle weren’t fattening up properly because his alfalfa and clover hay hadn’t been pollinated, leaving the feed lacking in important proteins. That connection “is something you just don’t think about,” Studer says. “That’s when it hit home to me just how important bees are to our food supply.”

Bees fly within about a two-mile radius from the apiary (the box which houses the hive), gathering nectar from flowering plants a drop at a time, visiting 50 to 100 flowers before reaching their nectar-storing capacity. The bee then returns to the hive, where it spreads the nectar throughout the comb and fans it with its wings to thicken it. The resulting honey — a healthy hive of 50,000 bees will produce 100 pounds of honey over the course of a year — produces food for the colony. Beekeepers gather a percentage of that for human consumption.

Commercial growers truck colonies of bees across state lines to pollinate everything from almond trees in California and citrus groves in Florida to apple orchards in Washington and blueberry bushes in Maine, making it “the largest agricultural migration in the world,” according to Richard Underhill, president of the Arkansas Beekeepers Association. Honey production, while better known to consumers, is actually a much smaller segment of the beekeeping industry.

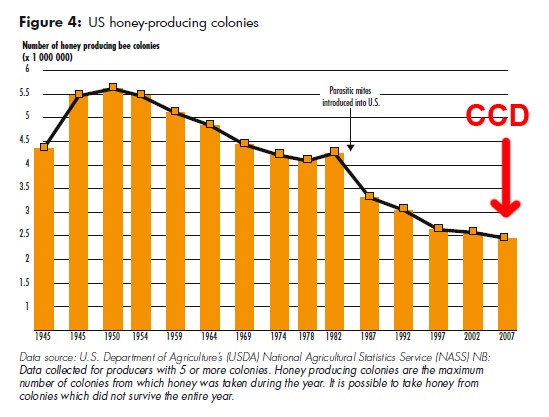

Bees play a vital role in U.S. food production, but since 2007 honeybees have been disappearing at an alarming rate. Scientists call it Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD), a phenomenon in which worker bees abruptly disappear from the hive, leaving the queen and honey behind. Why it occurs remains a mystery.

Beekeeper Bill Hughes of Brighton, Tennessee, has observed losses firsthand. Since 2008, his colonies have declined from 400 to 60. Hughes, who has been keeping bees for 20 years, has checked many of his apiaries only to find them empty, the bees not dead but simply vanished. Studer and his colleagues report that feral bees, too, are all but gone. “I used to catch wild swarms,” Hughes says, “but if they’ve been poisoned by insecticide, the bees won’t breed,” further reducing their numbers.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) estimates that 33 percent of bee colonies have collapsed nationally due to CCD (and in some regions, that number is closer to 50 percent). While colony losses are not unexpected, losses of this magnitude set off alarm bells. Underhill calls it “the largest historical die-off in the history of beekeeping.”

It turns out that honeybees have many foes: fungal parasites, Varroa and tracheal mites, diseases like chalkbrood, and a lack of nutritional diversity. Even the use of altered seeds to grow crops like soybeans may play a role. But among its biggest foes is the use of neonicotinoid pesticides, which have become more prevalent in the last decade.

“Bees have been described as the canary in the coal mine, since conditions in the environment tell us we’ve altered the environment — from the amount of chemicals we use to the effects of global warming,” Underhill says. The bee decline has scientists scrambling to better understand these complex creatures and what can be done to stop CCD before it becomes an agricultural crisis. Studer says the USDA is working in concert with a host of universities, conducting multiple studies to better understand the factors that impact the health of bees. But the answers may be five years away. “It’s extremely difficult with so many different variables both inside and outside the colony,” Studer says.

So as you spoon that dollop of honey onto your biscuit at Thanksgiving, don’t take that sweet treat for granted. Honeybees need our help.

Jane Schneider is editor of Memphis Parent.