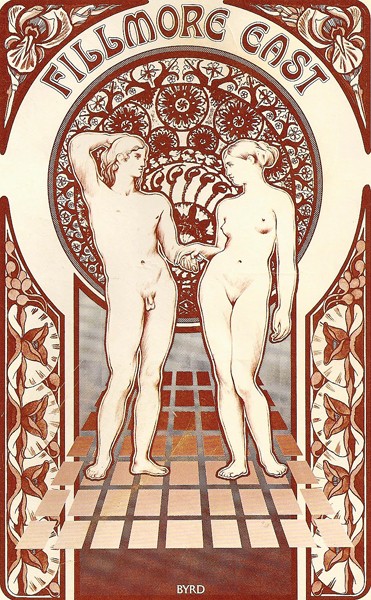

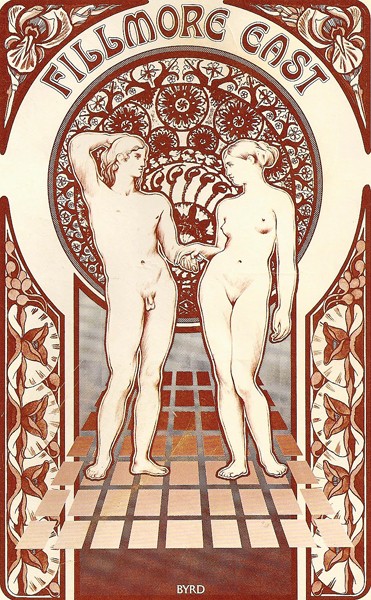

While going through an old box of stuff, I came across a program I had saved from the Fillmore East dated December 19, 1969. The Byrds were headlining that night, supported by Keith Emerson & the Nice and the San Francisco horn band the Sons of Champlin. As an added attraction, the immortal Dion DiMucci appeared to perform his latest hit, “Abraham, Martin, and John.”

That collectible brought back a lot of memories, most of them bad. When I was 20, I dropped out of college and moved to New York City. I was chasing the flimsiest of music offers from someone I barely knew. A high-school acquaintance had graduated from Yale as a poetry major and gotten a job in an apprentice program for Columbia Records. He had shown some of his work to the legendary talent scout and record producer John Hammond Sr., who encouraged him to find a collaborator to help transform his poetry into songs. I suppose I was the only musician he knew.

When “Tom” called, he mentioned the names of several friends we shared in common and asked me to come to New York with the understanding that I would eventually have a chance to audition for CBS. He said I could live rent-free in his apartment and only needed to contribute my share of grocery money. After calling a few people and asking if this guy was for real, I packed my guitar and a suitcase and flew to Manhattan.

As soon as I arrived, the problems began. I took a cab to the address I was given only to find a short-order grill there. The cabbie informed me that my friend lived above the restaurant. When I lugged my gear up four flights and found the apartment, the couch I was promised was already occupied by one of Tom’s college buddies who was waiting for renovations to be completed on his place. I was asked if I minded sleeping on the floor for a little while. No sooner had I caught my breath than Tom sat cross-legged on the floor and asked if he could play my guitar. Nobody played my guitar.

After I had reluctantly handed it over, I realized that he had no musical ability whatsoever. He was the kind of guy who had to look at his left hand when he changed chords, and his poetry consisted mainly of abstractions that only he understood. I thought briefly of returning to the airport and booking the first flight out, but I’d already told my friends I was going and didn’t want it to appear that I had turned tail and run. I knew that if anything was to be accomplished, we would have to start from scratch. While I was lying on the floor using my leather jacket as a pillow, I wondered what in the world I had gotten myself into.

Tom and I grew to dislike each other so much that I would deliver a melody to his cubicle in the morning, and he would write poems to fit during the workday. The problem was, his lyrics were mainly about some phantom girlfriend that I never saw and nothing else in the known world to which I could relate. Our hostility grew so bitter that he asked me to leave. I had never been kicked out of anywhere. I found a single room in a decaying brownstone on W. 82nd Street. It had a single sink that looked like it had been clogged since the Prohibition and a bathroom down the hall shared by 10 other tenants. My rent was $11 a week, and I still had to call home for financial help. The street was a magnet for hookers, junkies, and transients, but since I wore a frayed pea-coat from Navy surplus and a battered wide-brimmed fedora, I blended right in. After several tortuous months, we finally came up with a number of songs sufficient for an audition.

I stood with my guitar beside the desk of John Hammond. Just the knowledge that he had discovered Bob Dylan would have been intimidating enough, but since my dad was a fan of swing music, I also knew that Hammond had discovered Billie Holiday and put together the Benny Goodman Band. Now he was sitting a foot away, staring up at me. I began to play an up-tempo song featuring some of Tom’s metaphorical lyrics, but I couldn’t look him in the eye. When I had finished, Hammond proclaimed with a big smile on his face, “My, we have a singer here.”

He was impressed that I had once recorded for Sun Records and arranged a full demo session in the CBS Studios. I arrived early on the appointed day only to find a Vegas-like lounge singer in the studio while his slick manager was addressing Hammond as “Baby” in the control room. After apologizing for the delay, Hammond told me to go ahead and set up. I put my chord charts and lyric sheets on a music stand and went down the hallway to ease my severe cotton-mouth with a drink of water. When I returned, the lounge singer was gone, but so was all my music. Hammond sent the engineer racing after the pair, but when the out-of-breath engineer reappeared and told us he had shouted at the pair from the street but they jumped into a cab and sped off. They had stolen all of my notes.

Frozen with dread, I somehow managed to record the songs from memory. Ultimately, nothing came of the entire eight-month-long project. Hammond told me that because of a shakeup in the top brass at Columbia, “I no longer know where I’m at in this company.” After I had quietly returned to Tennessee, my former host informed me that Hammond had said, “A lot of people have stuck around a lot longer than he did.” Two years later, Hammond signed Bruce Springsteen to Columbia Records. Still and all, I’m the only artist in recorded history to have been produced by both Sam Phillips and John Hammond. It ain’t bragging if it’s true.

Randy Haspel writes the “Recycled Hippies” blog, where a version of this column first appeared.