The mission of the Indie Memphis Film Festival is to bring films to the Bluff City which we could not see otherwise. Some Indie Memphis films return to the big screen the next year, like American Fiction, which screened at last year’s festival and went on to win an Academy Award for writer/director Cord Jefferson. For the last 27 years, it has been an invaluable resource for both beginning and established filmmakers in the Mid-South. Early on, the festival launched the career of Memphis-based director Craig Brewer, whose recent limited series Fight Night was a huge hit for the Peacock streaming service. Many others have followed.

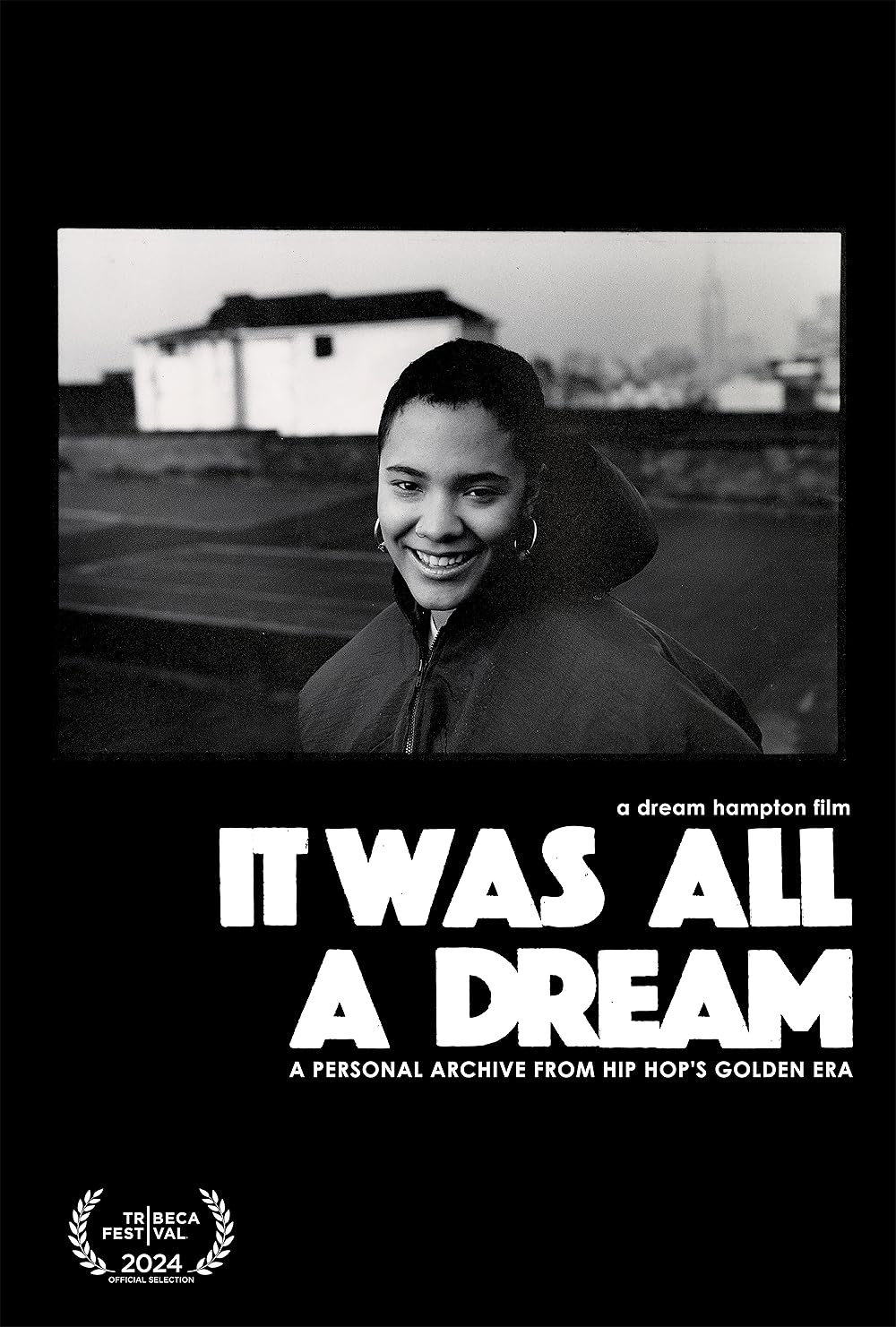

This year’s festival brings changes from the norm. First of all, it takes place later than usual, with the opening night film, It Was All a Dream, bowing on Thursday, November 14th, and running through Sunday, November 17th. There will be encore presentations at Malco’s Paradiso on Monday, November 18th, and Tuesday, November 19th. “We are having encores because our biggest complaint is that we have too many films back to back that people want to see. So that was a direct response to our audience,” says Kimel Fryer, executive director of Indie Memphis.

Opening night film It Was All a Dream is a documentary by dream hampton, a longtime music writer and filmmaker (who prefers the lowercase) from Detroit, Michigan. Her 2019 film Surviving R. Kelly earned a Peabody Award and was one of the biggest hits in Netflix history.

“I’m really excited to see how everyone thinks of our opening night film,” says Fryer.

It Was All a Dream is a memoir, of sorts, collecting hampton’s experiences covering the golden era of the hip-hop world in the 1990s. “I really enjoyed watching it, especially seeing footage of Biggie Smalls, Prodigy from Mobb Deep, Method Man, and even Snoop Dogg before they became icons. They’re just hungry artists. Even Q-Tip is in it, and the other night, Q-tip was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. So I was thinking about that as I was watching the awards. He was such a baby in this field, he had no clue 20, 30 years from now he was going to be on this stage,” says Fryer.

The festival is moving in space as well as time. While the festival will return to its longtime venue Malco Studio on the Square, there will be no screenings at Playhouse on the Square this year. The 400-seat Crosstown Theater will screen the opening night film and continue screenings throughout the long weekend. On Saturday at 11 a.m., it will also be the home of the Youth Film Fest. “This is the first year we’re combining the Youth Film Fest with the annual festival,” says Fryer. “That’s really cool, being able to allow the youth filmmakers to still have their own dedicated time, but also to be able to interact and see other films that are outside of their festival. We do have some films that are a little bit more family-friendly than what we have had in the past.”

Among those family-friendly films are a great crop of animated features, including Flow by Latvian director Gints Zilbalodis. Flow is a near wordless adventure that follows a cat and other animals as they try to escape a catastrophic flood in a leaky boat. The film has garnered wide acclaim in Europe after debuting at the Cannes Film Festival, and will represent Latvia in the International category at the Academy Awards.

“I thought it was interesting because, of course, when Kayla Myers, our director of programming, selected these films, we had no idea some of the more recent impacts from the hurricanes and things of that nature would happen,” says Fryer.

Julian Glander’s Boys Go to Jupiter is a coming-of-age story about Billy 5000, a teenager in Florida who finds himself tasked with caring for an egg from outer space. First-time director Glander is a veteran animator who did the vast majority of the work on the film himself. The Pittsburgh-based auteur told Cartoon Brew that he and executive producer Peisin Yang Lazo “… did the jobs of 100 people. I have no complaints — it’s been a lot of work, but it feels really good to make a movie independently, to not have meetings about everything and really own every creative decision.”

The festival’s third animated film, Memoir of a Snail by Australian animator Adam Elliot, is the story of Grace (Sarah Snook), a young woman who escapes the tedium of her life in 1970s Melbourne by collecting snails. When her father dies, she is separated from her twin brother Gilbert (Kodi Smit-McPhee) and put into an abusive foster home. We follow Grace as she navigates a difficult life, full of twists and turns, with only her snails as a constant comfort. “Memoir of a Snail is an adult animated film,” says Fryer. “Bring the kids at your own risk.”

The spirit of independence is what puts the “indie” in Indie Memphis. The festival has always been devoted to unique visions which question the status quo. Nickel Boys, the centerpiece film which will screen on Sunday night at Crosstown Theater, is by director RaMell Ross. “I’m really excited about that film,” says Fryer. “But also, it uses film as a critique. It’s based on the novel from Colson Whitehead that won a Pulitzer Prize.”

Nickel Boys takes place in 1960s Florida, where a Black teenager, Elwood (Ethan Cole Sharp), is committed to a reform school after being falsely accused of attempted car theft. There, he meets Turner (Brandon Wilson), and the two become fast friends. The film is shot by Jomo Fray, who was the cinematographer behind All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt, which opened last year’s Indie Memphis festival. It is highly unusual for its first-person perspective, which shifts back and forth between the two protagonists, so that you are put in the perspective of the characters, who are battling to keep their humanity in a deeply inhumane environment.

Fryer says bringing radical artistic works like these to Mid-South audiences is central to the organization’s mission. “I think that’s honestly one reason why people like Indie Memphis. Don’t get me wrong, people do like to see the very well-known films, the more commercial films, the ones that get a lot of press. But I think the people who enjoy coming to Indie Memphis also enjoy seeing things outside of the box, seeing things that push the narrative. And it makes sense when you think about Memphis. Memphis is never going to be this cookie-cutter place, and people who live here love it because it’s not.”

Funeral Arrangements

This year’s festival has a strong local focus, with seven features in the Hometowner category. One of the locals is a 15th anniversary screening of Funeral Arrangements by Anwar Jamison. The writer/director is low-key one of the most successful Memphis filmmakers from recent years, having produced, directed, and starred in Coming to Africa and its sequel, which were both big hits in Ghana and other African countries. Funeral Arrangements was his debut feature.

Anwar Jamison

“Man, talk about a passion project,” Jamison says. “I just think back to being in film school in the graduate program at the University of Memphis, and now, it’s a full-circle moment because I’m teaching at the University of Memphis, and I have grad students and I’m working on these projects. I look back like, ‘Wow! That was me!’ And now I understand why my professors were telling me no, and that I was crazy to try to do a feature film for my final project, when I only needed 15 minutes. But I’m like, ‘No, I have this script!’ We had a bunch of young, hungry crew members. No one had done a feature, whether it was the crew or the actors. We had a lot of theater students in it, and everybody was just like, ‘Wow, this would be cool!’ They all saw my vision. I had the script, being that I come from a writing background, and everybody really jumped on board to make it happen. I feel like it was the perfect storm of young creativity and energy, and it really showed in the final product. I’m proud of it!”

The idea for the film began with an incident at work. “Most of the things I’ve written start out as something that happened in real life, and then I take it and fictionalize it,” Jamison says. “It was based on an experience I had working a job that really was like that. I couldn’t be absent again, so I really lied to the supervisor and told him I had to go to a funeral. And he really said, ‘Bring me the death notice or the obituary.’ In real life, I didn’t do it, and he didn’t bother me. I ended up keeping my job. But as a writer, in my mind it was like, ‘Whoa, that would be funny. What if the guy really went to a funeral, and now he gets caught up in a situation?’ It just came from there.”

It was this idea that got Jamison’s talent noticed. “When I was an undergrad, actually in the very first screenwriting class that I took, my professor called the morning after we had the final project, which was to write the first act of a feature film. I’m like, ‘Why is this professor calling me?’ And she was like, ‘I really enjoyed the script. Could we use it as the example in class to read for the others?’ That let me know I was onto something.”

Jamison says he’s ready to celebrate the past and looking forward to the future. “I have the third Coming to Africa that I’m preparing for, and I hope to do in 2025, if all goes well, and wrap that up as a trilogy. But what I found, once you get there, there’s just so many stories that connect the diaspora and Ghana in so many ways. There’s so many natural stories to tell that I would love to keep telling them.”

Bluff City Chinese

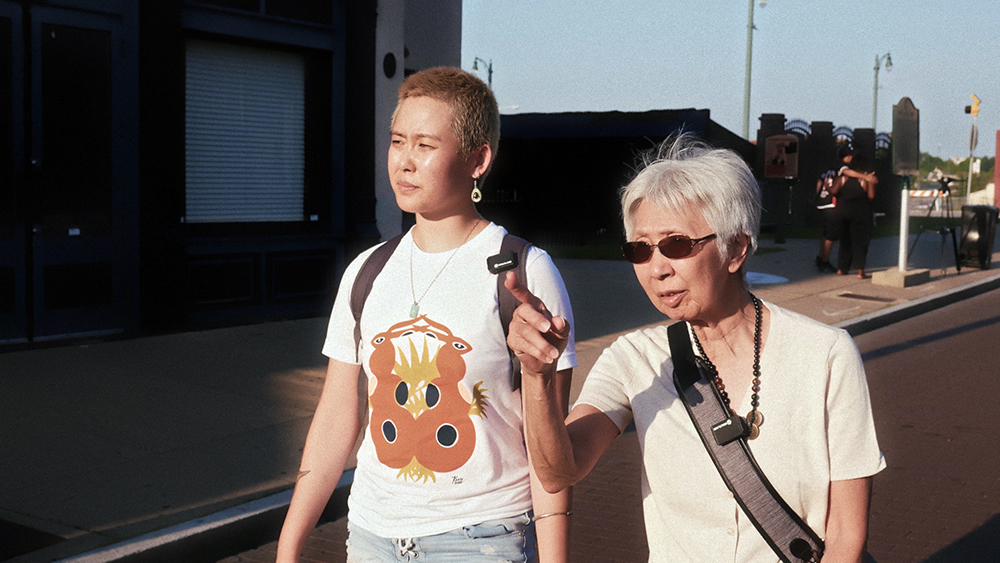

“I actually got into filmmaking through fashion,” says Thandi Cai. “I was working in textile art for a while, and I was making a lot of costumes. A lot of the things that I was making didn’t really make sense in our reality right now, so I was starting to build stories around the costumes I was making. Then I wanted to create films out of those costumes and realized, ‘Oh, this is a potential career that I could follow!’ So then I started doing videography commercially, in addition to all these little small fashion films on the side. Film and video started becoming more of my storytelling practice, and a tool of how I could explain and share what I was learning with the world.”

They began work on their documentary feature debut Bluff City Chinese in 2020. “It originally started out as an oral history project. And because, like I said, I think film is such a powerful tool, I started recording oral histories visually. But then didn’t know what we were going to do with it.”

Several people suggested Cai apply for an Indie Grant. The Indie Memphis program, originated by Memphis filmmaker Mark Jones, awards two $15,000 grants each year, selected from dozens of applications by local filmmakers. Cai was awarded the grant in 2022. “I really didn’t have very high expectations of getting it, so I was just blown away and really grateful that we did.”

Indie Grants are nominally for short films, but Cai said their project grew to 45 minutes. “It was just a huge, huge help. I think it made a really big difference because prior to getting that money, the vision for the documentary was very DIY, really lo-fi. I was not expecting this to be a full-fledged film, really. It was like, let’s try to get these oral histories out there by whatever we need to do to get it out there. To be able to have that money to really just dive in and see how far we could take the actual production value was just enormous. And yeah, it’s much more beautiful than I ever thought we could make it, and I think that will just help us be able to share these stories with more people.”

Cai grew up in Memphis, but they say it wasn’t until later in their life that they were aware of the long legacy of Chinese immigrants who had made Memphis home. “That’s the crazy part! Growing up as a Chinese American in Memphis, I didn’t learn about any of this until 2020, and it was only because of all the things that were happening in the world, and especially to people who look like me. That’s why I’m pushing this film so hard because this isn’t something that a lot of us get to learn when we’re growing up. There haven’t been a lot of discussions or platforms that are sharing these stories. I consider a lot of the people that we talk about as my ancestors or my elders or my community members, but I didn’t meet a lot of them until very recently. I really hope that no matter how late someone is in their journey, that when they do find this connection to their roots, they feel like they can just jump in and embrace it.”

Marc Gasol: Memphis Made

Director Michael Blevins is the head of video post-production for the Memphis Grizzlies. “Basically, the way I describe it is anything that gets edited, it comes through me and my team,” he says. “So the intro video that gets played before the game, I will edit that, and commercial spots or behind-the-scenes stuff about the current team.”

Before coming to Memphis in 2016, Blevins had previously been with the Chicago Bears, the Houston Astros (“I believe we had one of the worst records in baseball history,” he says), and the San Francisco 49ers. “Then I came here, and I overlapped with the subject of the documentary, Marc Gasol, for his last three seasons in Memphis. So I got to know him and Mike Conley really well.”

Blevins normally works on a very quick turnaround, but the world of documentary films is quite different. It requires patience and flexibility. “In a project like this, the scope becomes bigger. In terms of production, in terms of lining up interviews, shooting, all that stuff, we were able to spend seven months on it. But in the same time, you then have 50 interviews. You got to tell an hour-and-a-half story basically. So a month or two to edit something in a vacuum sounds great compared to the usually quick turnaround of a current NBA team. But then you want to tell a story perfect because it is telling his whole story of his professional basketball career. So it’s not like with current content, when there’s always another game coming up. This is it. It’s a little dramatic, and he has a sense of humor, so we laugh about it. But it’s like writing somebody’s obituary. You’re not going to get another chance to do it. It’s their basketball career.”

It was important to Blevins to go beyond the surface image of the star basketball player and uncover the emotions that drove him. “Marc is a super competitive guy, and the big thing was, as the people that knew him say — and a lot of people didn’t realize this from the outside — is that competitiveness would spill over a lot of times in terms of trying to deal with teammates. That’s one of my favorite segments in the film. It’s like 20 minutes about different stories people were telling about Marc being very competitive and looking back at everything through a different lens of today. And I think he looks at it very differently, where he felt like he could have been better. But he knows in his head, and different players say it in the film, they needed him to be like that. If that was a spillover of him chewing him out during the game and then after the time-out was over, he was going to give it all and make a play on defense to save that guy, or make a play on offense to set that guy up. It was going to be worth it. But I think athletes, and all of us in general, as we get older, sometimes if you reach success or you’re happy with what your career has done, you start to look back and think, ‘What was the cost of that?’”

Cubic Zirconia

Jackson, Tennessee, native Jaron Lockridge’s Cubic Zirconia is the only locally produced narrative feature in a field of thoughtful documentaries. “I’ve been filmmaking now since about 2016, and just self-producing feature films, and going that route now that technology makes it easier. I just decided to jump out there and don’t take no for an answer.”

Jaron Lockridge

Lockridge, who began as a writer, produces, directs, lights, shoots, and edits his films. “When I found quickly that I couldn’t afford to hire people to produce my work, I just became that multi-tool to start producing my own work, and getting to this point now.”

Cubic Zirconia takes place in what Lockridge calls The Stix Universe, which is tied into his self-produced web series. “It’s a good old-fashioned crime mystery, I like to say. It’s similar to something like Prisoners or maybe even a touch of Se7en, for people who like those type of movies. It follows a missing family, and these detectives are trying to find some answers to what happened. When they locate the deceased mother of this missing family, then it’s just an all-out blitz to find the children and figure out the ‘why’ behind it all. You’ve kind of got to pay attention. But when it comes to the end and you realize what’s happened, I believe it’ll be a shocker to a lot of the audience members.”

Keith L. Johnson stars as the police detective on the case. “I’ve worked with him several times before. He’s one of my regulars, so we just have a great chemistry together to the point where I can just give him a script and give him very little direction. He just understands my work.”

Memphians Kate Mobley and Kenon Walker are also veterans of the Stix Universe. Terry Giles is a newcomer. “He was one that I haven’t worked with before, and he was a very pleasant surprise. He only has a small time on the movie, but when you see him, you notice him. He commands the screen, and he’s a talent that I’m looking forward to working with again. I’m very excited about the performances in this movie.”

Passes and individual screening tickets are on sale at imff24.indiememphis.org. There, you can also find a full schedule for this weekend’s screenings and events.