Dreams of Kamp Kiwani get Kailey Hilton through the school year. The camp is about 75 miles east of Memphis on a massive 1,250-acre site in Middleton, Tennessee. But in her mind, Hilton is swimming or rowing in Lake Okalowa, running the obstacle course, loosing arrows on the archery field, eating in the Thunderbird Dining Hall, or playing Ga Ga Ball with her friends.

And she certainly thinks about the horses.

“We get to ride them [around] camp and see parts of it we’re not used to seeing,” Hilton says. “We get to learn more about them, too. We get to see how they react and how to handle them if they get stuck in the brush or something.”

Hilton has been going to Kamp Kiwani since she was in the third grade, through her Girl Scouts troop with Heart of the South. Next year, she’ll be a Wrangler in Training, a sort of camp counselor. But even now, she likes seeing the younger kids — the Daisy Girl Scouts — and watching them grow up at camp just as she did. For Hilton, all of these hopes and fond memories go back to Kamp Kiwani.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Community Foundation of Greater Memphis CEO Bob Fockler and Executive Vice President Sutton Mora Hayes

“That’s what gets me through the school year,” she says. “I know I get to go to camp and have that sense of community there.”

Many of these magical camp moments and memories would not be possible without Theodora Trezevant Neely. You won’t find her name etched on any building in Memphis, but Neely’s name rings loud in the laughter and learning of inner-city kids at out-of-the-city summer camps.

For more than 40 years, Neely has annually sent 200 Memphis kids to camp. She grew up in Memphis but lived most of her adult life elsewhere. She didn’t have children and didn’t even really know who ran camps around here. It’s not perfectly clear why Trezevant Neely chose Memphis kids and summer camps as her mission, but she did, and Neely’s choice has sent more than 8,000 Memphis kids to summer camp.

“I heard that she had a passion for getting kids off the mean streets and onto someplace green in the summer,” says Bob Fockler, CEO of the Community Foundation of Greater Memphis (CFGM). “She left a significant portion of her estate — that has ended up here at the Community Foundation — to send kids from urban Memphis to places where they can dig in the dirt.”

Largest in Tennessee

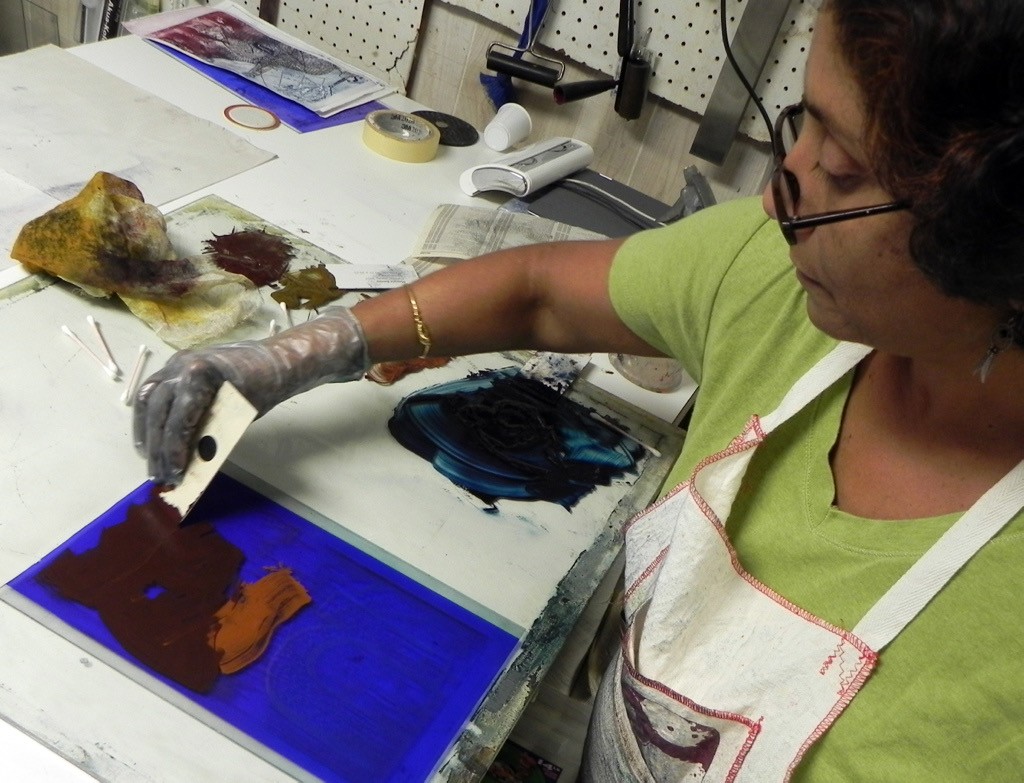

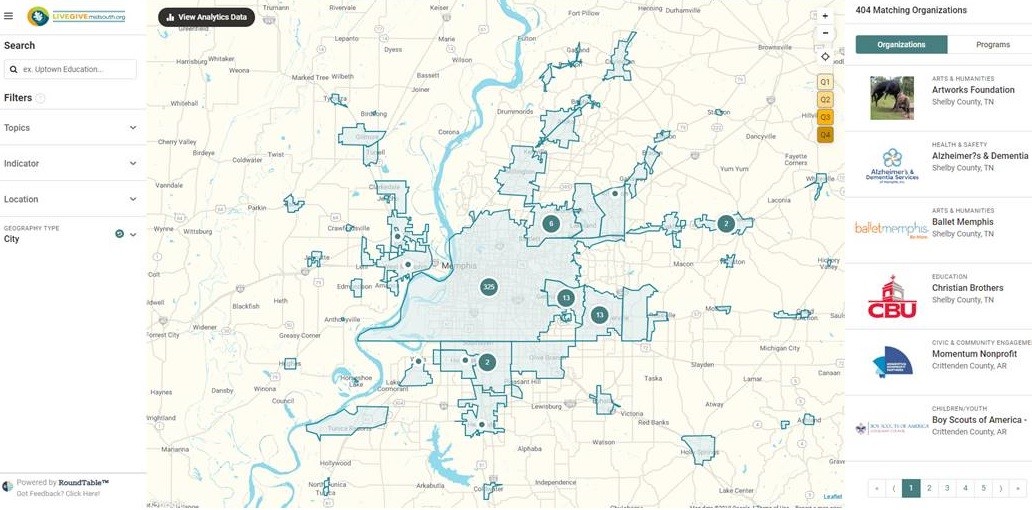

This has been the work of the Community Foundation for the last 50 years. It’s not always kids and camp. Over the last 10 years, the foundation has focused on education. But it also works to improve the health of Memphis through community development grants, and the health of Memphians with grants to improve health care. (Think Church Health, MIFA, and the Mid-South Food Bank.) The foundation also invests in support for the arts, the environment, religion, and more.

If you’ve ever walked across Big River Crossing or watched a show at Playhouse on the Square or taken a selfie at the I (Heart) Soulsville mural, you’ve reaped the benefits of the Community Foundation’s work. If you’ve ever been thankful for the work of Just City, MLK50, or the Mid-South Peace & Justice Center, thank the Community Foundation.

Over the last 50 years, the foundation has touched nearly every sector and social class of Memphis (and has done work in Mississippi and Arkansas, too).

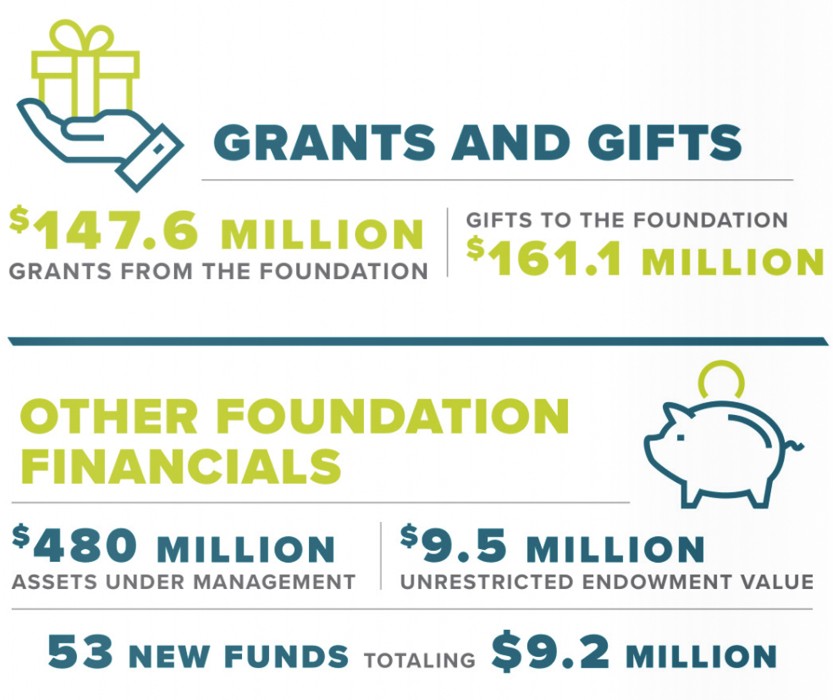

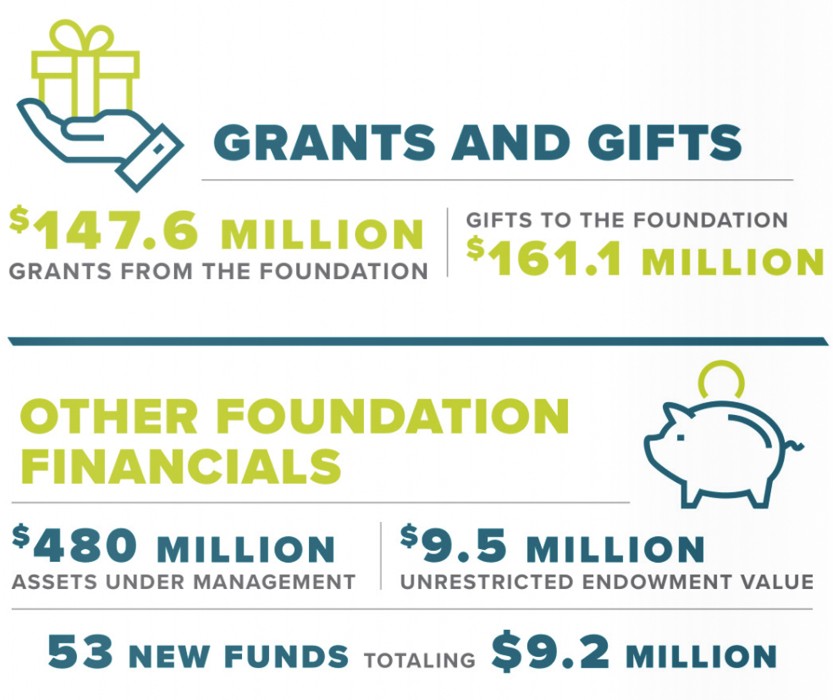

It is the largest grant-making organization in Tennessee and one of the largest in the Southeast. The Community Foundation has invested around $1.5 billion into the Mid-South since the organization was founded in 1969. In its most recent fiscal year, the foundation granted $147.6 million to nonprofit organizations — 6,733 grants to 1,864 organizations — from 618 funds that the foundation manages.

The foundation is a conduit between donors and nonprofit organizations. Many donors know they want to help but might not know how. The foundation is plugged into the Memphis nonprofit community and can help donors find the right spot to contribute their support.

“Community foundations are important because they centralize donor funds while keeping a pulse on community needs,” says Kevin Dean, CEO of Momentum Nonprofit Partners in Memphis. “They also ensure that donors’ investments are actually reaching the community. We live in an age where many foundations’ credibility is called into question, as we’ve seen in the Trump Foundation debacle. Community foundations are a way for donors to feel confident that their money is being properly and ethically utilized.”

In the Beginning

The CFGM works on some of Memphis’ toughest issues, which is appropriate, since its beginnings sprung from one of the city’s toughest times — the 1968 Sanitation Workers Strike and the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in that tumultuous year. Memphis had been a battleground for weeks — National Guard tanks literally rolled on Beale Street. When the dust settled, the city was ravaged. It needed help to rebuild. Enter an organization called Future Memphis.

The group was a collective of company leaders from across the city that had formed in 1961 to advocate for their vision of Memphis’ future. That vision included pushing for the annexation of huge parts of what is now modern Memphis (Cordova, Whitehaven, and more), liquor by the drink in Tennessee, running I-40 through Overton Park, consolidating the city and county government, and creating what is now the Memphis and Shelby County Airport Authority.

But more broadly, the group’s incorporation papers said they wanted to “provide a source of backing for worthy projects” and “coordinate and support the efforts of other organizations.” To help rebuild Memphis after the events of 1968, Future Memphis established what was then simply called The Community Foundation, funded with an initial $1 million grant from pharmaceutical magnate, Abe Plough.

“It was a group of people coming together — some wealthy, some not so wealthy — who cared about making Memphis a better place,” Fockler says. “They started with fixing the city, but I think pretty soon they just started pushing for the things they cared about.”

Ed Williams was Future Memphis’ last executive director. He talked with Memphis public library historian Barbara Flannery in 1996, when Future Memphis was winding itself down. Williams said the group had, basically, been successful enough to put itself out of business, an oft-stated goal of many nonprofits.

“If you jump 34 years into the future from 1961 and think of all the nonprofits that exist today — and I mean that in a positive sense — we literally have a nonprofit organization to deal with almost every conceivable problem,” Williams said in 1996.

He called the Community Foundation one of the “real backbones of charitable giving in the city of Memphis.” Future Memphis and the foundation operated quietly and behind the scenes, Williams said, but touched many parts of Memphis life — from the Memphis Zoo to schools, from economic development to city planning.

“Probably the average citizen would have no idea of these accomplishments,” Williams said. “That’s why we felt it was important that you, here in the history department, have access to all of [our papers] because it’s going to be important in years to come. People will look back and say, ‘Well, how did this happen?'”

Steady Growth

Assets for CFGM have grown steadily over the years. It had about $90 million in 1996 when Williams spoke to historian Flannery. Its assets hit $100 million in 1997, the same year it moved into its current Union Avenue location, formerly the Hinds-Smythe Cosmopolitan Funeral Home.

In 1997, Carol and Jim Prentiss made the then-largest-ever grant in Memphis — $5 million to the Memphis Zoo — through their fund at the Community Foundation. (Statues of the Prentisses can still be found by the wading pool close to the zoo’s entrance.)

In 2000, Herman Morris was elected as the foundation board’s first African-American chairman. By 2001, foundation assets were at $200 million with 800 funds. In 2003, Fockler was named the organization’s third CEO. (His father, John Fockler, was the first.) In 2007, assets reached $300 million with more than 900 funds.

In 2009, the foundation was the county’s fiscal agent in purchasing the Shelby Farms Greenline. In 2010, the Community Foundation launched Give 365, a dollar-a-day giving program. In 2012, the foundation was the fiscal agent for the Harahan Bridge Trail Project, which became Big River Crossing.

Paul Morris was project director for Big River Crossing and says the foundation was “instrumental” in making it happen. “We worked with donors who chose the Community Foundation as their vehicle for giving to the project,” Morris says. “That’s what CFGM does — it facilitates a connection between generous donors and important community projects. So many great things have happened in Memphis because of these connections forged by CFGM.”

In 2014, the foundation worked with the city to establish the Sexual Assault Resource Fund. Private donors to that fund helped the Memphis Police Department clear its backlog of 12,374 untested rape cases.

In 2015, assets reached $500 million with more than 1,000 funds. Last year, the foundation launched MLK50: The Next Step Forward, building on Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s platform of effecting real and systemic change.

This year is the Community Foundation’s 50th anniversary. But instead of resting on its past successes, foundation leaders are changing how they approach future problems.

Moving Ahead

The Community Foundation still works quietly and behind the scenes. Much of that work is done at the behest and direction of the nearly 800 families with funds invested. But in the 1990s, the foundation began listening to voices in the community. A group of volunteers began helming a committee to decide where to give funds collected from donors in the Community Partnership Fund. That volunteer committee — comprised of people from all walks of Memphis life — had the final say on how to give nearly $1 million to nonprofits last year.

As a part of a new strategic plan approved in December, the community’s influence will be increased through the newly created Forever Fund, an endowment funded by private donors but with investments directed by members of the community.

“We need a community-based voice for grant-making because we know that the priorities of the average person on the street may be different than those of the great, private foundations,” Fockler says. “So, our board of governors said we really need to secure and grow our own grant-making voice.”

Sutton Mora Hayes, CFGM’s executive vice president, says that allowing those committee members to pick what they fund sets the Community Foundation apart from the other private foundations in Memphis.

“There are times when our committees make grants, and [Fockler] and I are both like, well, this may not work out,” Mora Hayes says. “That’s another part of our grant-making. We are responding to what we’re hearing from the community and what our community volunteers are saying they want to fund.”

The Community Foundation is poised for another shift, due to its new strategic plan. The foundation has long been a favorite of government entities thanks to its neutral stance, “because we don’t have our own agenda,” Fockler says. But that stance is shifting.

“It’s a shift from not having an opinion to having an opinion based on what we’re hearing from our partners in the community,” Mora Hayes says. That opinion is based on feedback from the foundation’s board, its leaders, its community partners, and its volunteer committee members. A blend of those opinions will inform how the foundation’s money is spent.

For example, Mora Hayes says the foundation did a grant round last year for the MLK50 event. However, the National Civil Rights Museum wanted the community to look beyond the 50th commemoration of King’s assassination and use it as a springboard to make lasting changes. “We asked applicants of that round questions we’d never outright asked before — questions around diversity of staff, the diversity of your board, the diversity of who you are serving,” Mora Hayes says. “And that’s the shift. Instead of never asking, we asked. It’s important to have that conversation because in this city we need to be having a real conversation around diversity, equity, and inclusion.”

The foundation will also change how it measures success. In the past, it was enough to know that the organization was injecting $150 million into the community every year and putting it where its 800 funding donors wanted.

Fockler says the foundation is not moving away from supporting its donors or their collective impact, but it is moving toward “a greater responsibility for our community impact.”

The Forever Fund will help accomplish part of this mission, he says. But the foundation will take that move toward community responsiveness a step further this fall with a series of community meetings and working with Innovate Memphis and BLDG Memphis. Thoughts from the community at those meetings will inform the future of the foundation’s philosophy and mission, Fockler says.

“It gets down to moving the needles on the city’s problems. Did the foundation’s grant really improve poverty or health disparities? Were those grants successful? What even are the needles of success that we need to be measuring? … Then we’ll be in a space where we can say, for example, here are the indicators in 2020,” Mora Hayes says. “We’re going to look at them again in 2025 and see what’s moving, what’s not, and what needs to change.”

Planning for Plough’s Exit

In 1960, another Memphis-based foundation began making grants. Abe Plough, the same man who invested early in the Community Foundation, started the Plough Foundation.

Since then, the Plough Foundation has made more than $300 million in grants to local nonprofits, according to information it released two weeks ago. The Plough Foundation helped create the Memphis and Shelby County Crime Commission and build the “I Am a Man Plaza” Downtown, among many other projects. Plough — along with the CFGM, the Assisi Foundation, Pyramid Peak Foundation, Hyde Foundation, and Poplar Foundation — is one of the largest foundations in town. But two weeks ago, Plough officials announced the foundation would close within four years.

Mora Hayes says the news has the Memphis philanthropic community considering how it will fill the gap. “We’re not going to unplug the remnants of that one billionaire, find another billionaire, and plug it in there,” Hayes says. “How does the community come together and figure out how to balance the loss of the Plough Foundation?”

Mora Hayes says it’s an excellent time for the Community Foundation to talk about its community-based funds and its Give 365 program. While those programs may not be invested with Plough-level money, they foster a sense of community.

Fockler says it is up to the Community Foundation to answer how the community deals with the loss of the Plough Foundation, adding that they aren’t “waiting for that next billionaire to show up.” The foundation is working hard to groom the next generation of philanthropists in Memphis.

“The answer isn’t plug-and-play billionaires, but it’s a lot of regular Memphians who care about the city, represented by those 800 families, and we’re trying to expand that,” Fockler says. “It’s the dozens and hundreds of families of Memphis who are going to make a difference and step into the shoes of the Ploughs.”

Poor and Generous

Memphis was the poorest big city in America in 2016. The U.S. Census Bureau hasn’t updated its data for 2019, but it’s probably safe to say the city is still close to the top of that list.

So there’s a real irony in the fact that Memphis was the most generous big city in America in 2017 and 2018. The Chronicle of Philanthropy hasn’t updated its data for 2019, but it’s probably safe to say the city is still close to the top of that list.

Much of the city’s generosity in recent years was spurred by matching grants made for education by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The Community Foundation facilitated much of that giving. Fockler says education will continue to be a big category for the foundation’s donors, but much of the Gates Foundation money has been spent on programs for which it was intended.

“Other cities in similar situations, in terms of how their city is made up and their poverty levels, don’t have that same kind of response,” Mora Hayes says. “Our city is very interesting, in that our donors have consistently stepped up and tried to make things better, even though we’re not the richest of cities.”

When Theodora Trezevant Neely died in 1961, she never could have guessed that because of her generosity, she’s be sending Memphis kids to camp for the next 58 years. But Neely left a legacy that makes Memphis a better place. And for 50 years, that’s been the Community Foundation’s stock in trade.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Community Foundation of Greater Memphis

Community Foundation of Greater Memphis  Community Foundation of Greater Memphis

Community Foundation of Greater Memphis  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks