They are still fighting the war.

Not the “War Between the States” or the “War for Southern Independence,” as they call it, but local Confederate heritage groups say they will continue to fight the new names of three Memphis parks.

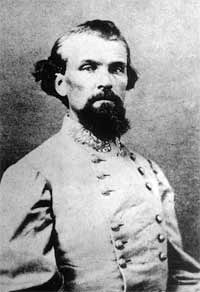

The Memphis City Council approved a resolution in February 2013 to change the name of Nathan Bedford Forrest Park to Health Sciences Park, Jefferson Davis Park to Mississippi River Park, and Confederate Park to Memphis Park.

Some residents and a group called Citizens to Save Our Parks (CSOP) filed a lawsuit in May 2013 to block the new names. A judge dismissed the suit in August saying the group had no legal standing to sue.

Toby Sells

Toby Sells

An old-time band plays some Confederate favorites during Saturday’s rededication of the Jefferson Davis statue.

But CSOP vowed to fight on. On Facebook, the group said it had filed an appeal, noting “this isn’t over.” They’ve launched a fund-raiser for the effort, a one-man show “Beyond Glory” that will be staged at the Orpheum Theatre next month.

Confederate heritage groups gathered in Memphis Park on Saturday to rededicate the park’s statue of Jefferson Davis on the 50th anniversary of its first dedication in 1964. Some of the men wore period clothing. Some of the women wore big hats and white gloves. Confederate flags were prominent on pins, neckties, and in a flower arrangement. The flag was also part of a parade of flags that stood next to the American flag, the Tennessee flag, and the Christian flag.

Mark Buchanan is the commander of the Memphis Brigade of the Sons of Confederate Veterans and president of CSOP. He said many people — even supporters — question why they continue to fight the new names.

“It’s in our DNA. It’s part of our faith. It’s part of our nation,” Buchanan said. “To try to erase our past is to deny who we are as Americans. It’s simply and undeniably who we are. Good, bad, happy, or sad, we can’t change it. We shouldn’t ignore it and we shouldn’t erase it.”

The day was rife with subtle jabs at the decision to rename the parks and to those behind the decision. Lee Millar, president of the General Forest Historical Society, held up the group’s permit for the event, which, he said, was labeled “Confederate Park.” The realization was met with a “here, here!” from the crowd.

“The park service still recognizes this as the correct park,” Millar said. “Unfortunately, it’s other people in the city, like the permit office, who are getting instructions from above, and I don’t mean ‘that’ above. They are trying to call it something else.”

Shelby County Mayor Mark Luttrell named Saturday, October 18th “Jefferson Davis Day,” in a signed proclamation from his office. Luttrell did not appear at the gathering but Millar said Luttrell is a “great and devoted proponent of American history, particularly ‘our’ history.” Luttrell’s proclamation called Davis a “great leader” and he “established an example of greatness for future generation through his leadership and public service.”

After his defeat in the Civil War, Davis lived in Memphis and was president of a short-lived life insurance company.