I interviewed educator and Take ’em Down 901 activist Tami Sawyer Friday, August 25, a week after protests to remove Confederate memorials from Memphis’ public parks ended with police action and arrests. In the same week’s time, Mayor Jim Strickland pushed back against critics and the public conversation about appropriate means/timetables for removing inappropriate statues honoring Confederate President Jefferson Davis, and Nathan Bedford Forrest, a slave trader, Klansman, and general of the Confederate army. Things got personal and cloudy, as they often do when individual feelings become proxy for public narratives.

The interview was condensed into a profile for a Memphis Flyer cover story — a package covering various aspects of the Confederate monument debate. Soundbites don’t always do Sawyer justice, so here’s a more complete picture.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Tami Sawyer, #takeemdown organizer and activist

Memphis Flyer: How big is this fight over the statues? What does it really look like?

Tami Sawyer: Ursula Madden says 10% of Memphis is on our side 80% doesn’t care and 10% is against us. I don’t think those are scientific numbers.

Maybe not scientific, but do they sound right to you? There’s always a lot of indifference, whatever the issue is.

It feels like it’s probably 30 – 40- 30. And the 40 that don’t care aren’t necessarily against us or against me. The 30 that cares though, are loud, vehement, and angry.

I suspect almost everybody has some opinion on this. There’s certainly no shortage of comments online.

I can’t read it. I haven’t watched video of myself because I can’t ignore the comments. And the way Facebook works now the comments start automatically. The news stations live streamed a lot of things we’ve done instead of just recording them, so those comments scroll across the screen while you’re watching the live video. I just can’t, you know? Because, like today when my flight touched down the first text I get says, “So, I hear you’re running for Mayor.” There’s all this conjecture.

Are you running for Mayor? Is this the big announcement story? I don’t think I’m prepared for the big announcement story.

No, I’m not. I couldn’t run for Mayor off this. Well, maybe I could. I’ll say I could, but I don’t think it would be a smart idea. It would be inauthentic to use this as a launching pad. I do this because I care about it. I am trying to tie politics into it, though because I don’t think we’ve had people-oriented leadership in Memphis. I hope that people are paying attention to the possibility of having leaders who are oriented with them, not the East Poplar business community.

So where did the rumor you’re running for Mayor come from? Detractors who think you’re just doing all this for attention or is it wishful thinking from supporters?

I think a large part of it is detractors. They think this is all a political ploy. They say I’m a demagogue who’s leading the people into bloodshed for my own political gain. At the end of the day 1% of Memphians vote, so unless I was leading the people to bloodshed via voter registration… You know? There is a feeling or assumption that this is all for my own personal profile — my own political profile. I put my family at risk. My parents are business people. My sibling is a business person. And I put their livelihood at risk daily when I go up against the big guys. [pullquote-2]

No matter how supportive they may be, that’s got to create stress.

Yes, it creates stress in the family. They’re supportive but it’s hard not to sometimes say. “Oh I wish you’d just have a seat.”

The same week I turned 50 I posted to Facebook a 20-year-old short story about being caught in the middle of a shootout in CK’s coffee house and noted that it was more or less a blow-by-blow account of a thing that actually happened to me and my wife. 20 years after the fact my mom still freaked out a little — parents wanting their kids to be safe runs deep.

My parents were out of town at the height of everything last week. So, to get a text from your child no matter how old I am — I’m 35 — to get a text from me saying, “Hey here’s my new number because I was woken up this morning by white supremacist on my cell phone…”. That’s tough. I recognize the stress and I do worry. So we have a little system.They always know where I am and they always know when I’m home. So at this last protest they went to a fundraiser and someone comes up to them and says seven people were just arrested, have you talked to your daughter?

Yes. Exactly. That’s got to be really hard for everybody.

Every time we talk about the impact on the family, the bottom line is “We want you to be safe. Even if you continue this path, we’ve got to know that you’re going to be safe.” I’m 35. I’m single. I’m childless. I live alone. My address is public record because I’ve run for public office. At one point my phone number was public record because somebody decided it was cool to post it on TV.

I remember seeing that. They showed a press release or something and didn’t blur out the number.

Channel-3, in their haste to break news, held a copy of the press release in their hand, took a photo and posted that photo like, “Here’s the press release!” Then there was a video. I was so panicked I went off on everybody 3, 13, 24 — “Anyone who’s ever said my name never say my name again. I quit.” (Laughter). You know, I never had a plan. I stepped out three years ago doing this stuff because I couldn’t believe we lived here and it was so quiet. How are we the home of the end — well, almost the end — of the Civil Rights Movement? I guess that makes sense, you know? Martin Luther King died here and it feels like a lot of hope and a lot of gumption died here too. Now we’re really stuck on History, not progress and I think that’s what makes me sad.

That reminds me of a long afternoon at Judge D’Army Bailey’s home in Hein Park. He was frustrated because he never wanted the National Civil Rights Museum to be “History under glass.” He wanted it to be a nexus or flashpoint for a living, progressing movement…

I think the museum with its expansion and programming…

Oh sure, I’m not criticizing the museum. It’s really grown and evolved its mission.

I grew up in the museum. My dad was CFO when I was in high school, so I used to walk in the back door. I remember back then it was just a place you went and visited once. You brought relatives when they came to town and there wasn’t much else going on.

Exactly. A place to look back at something that happened not a place you experienced something that was happening. That’s what frustrated Bailey — and you just sounded a lot like him.

That’s why MLK 50 can’t be just about the remembrance. 50 years later what gains can we say he made? And I have a complicated relationship with that statement because I’m second-generation college educated on one side of my family, and third-generation on the other. I graduated from St. Mary’s. My parents are considered upper middle class in Memphis. I’m considered upper middle class for Memphis. I’ve never wanted economically for much. So my story is not the story of the average black person or low-income person in Memphis. It’s like I told my dad just a week ago, everything they gave me they gave me with a dose of reality. We were never those kids who were allowed to believe we had made it. My mama was like, ‘Y’all are one generation from the hood.’

So it’s not the average story, it’s still part of the story.

When Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote The Case for Reparations, he wrote about a family who thought they bought a house in Chicago only to find out they’d been renting the whole time because of redlining and mortgage fraud. And with the loss of that home, the entire family spirals back into poverty. That’s the story. There’s no such thing as black wealth in our country. Even with people we idolize like Jay-Z or Beyonce — pull the roster of their cousins and family members and you will not find a wealthy generation. For example, Paris Hilton — all of her her generation and her parents’ generation have some wealth. It may be “poor” wealth — a million dollars — or true wealth like Paris. And its wealth because they have enough money for the next two or three generations to never experience poverty. So here in Memphis we have people with money and we have people whose children will have some comfort but, for example, I am probably two or three tough incidents in my life away from going from middle class into being impoverished. There’s a racial wealth gap we’re experiencing here, and we refuse to acknowledge it. There’s a lot of old white money making a lot of decisions in a majority-black city. And there’s no such thing as old black money, so the power structure is skewed. We’re looking at a scientific story here — a comedic line up of what Jim Crow and the following racist policies such as redlining and gerrymandering have done — and the impact of that story on people’s abilities, not to just survive, but grow.

That story’s never really allowed to have much of a public life. It gets lost in more sensational or ideological content.

We don’t have those conversations. The conversations we have are about how black people, poor white people, and brown people are uneducated and reckless, and don’t care about their kids, and have too much sex so they have too many kids, and they’re killing each other and stealing from each other, and they don’t care about anything. We won’t talk about everything I just said. We don’t talk about what it means to spend more money on cops than education or to build more prisons than schools.

Right. It’s all supermarket tabloid headlines and comment section trolling. Numbers show trends, but, “Let’s talk about personal responsibility.”

I had someone ask me about personal responsibility once. I was like, “Yes that’s real.” People have to have personal responsibility. You pick up a gun and rob somebody, you made a bad decision. But now let’s talk about what real social social justice looks like. For every crime, there’s a story. You know we idolize New York gangs today — the Italian gangs, and the Irish gangs that arose in the 20th-Century because of the sheer levels of poverty the Italian and Irish immigrants were experiencing and because of what prohibition meant for the money they could make off liquor sales. But today we don’t talk about “white on white crime” or “Irish on Irish crime” or “Italian on Italian crime.” Instead we watch it on the big screens, and the gangsters get to play themselves.”

Great point. I have three paintings in my house depicting the evolution of the gangs from Jewish to Irish and Italian and eventually Columbian. Organized crime played a real part in moving these groups out of the slums. But before I go down that rabbit hole, let’s talk about the Confederate statues.

Okay.

I’m a big believer that language shapes us. Stories shape us — our identity. So, while taking down a bunch of statues won’t instantly solve crime or poverty, what you want to accomplish here is a real thing that will have real consequences. Critics want to know why you’re putting so much effort into something symbolic when you could be working on the big problems. So is changing the story— that these guys were great men — real, or is it symbolic?

It’s both. It’s not just symbolic if we are able to continue a movement out of this. If we’re able to change conversations and make them about what social, racial, and economic justice really looks like. It’s not more than symbolic if the statues come down and everyone goes home and says ‘racism is solved in Memphis’, which is my fear. It’s more than symbolic because you’re in a 65% black City with a founder of the KKK, or Grand Wizard, or whatever big man he was in the early days of the Ku Klux Klan. And we’ve also got Jefferson Davis, the president of the Confederacy. I can tell you all the stories about what they said or what they did, but the bottom line is, they felt they were superior to black people and their treatment of black people was odious at best, no matter what Nathan Bedford Forrest did when he got dementia. Don’t Give A fuck, and you can print that. I don’t care what you renounce at 85, or whatever.

His defenders prioritize a few incidents that don’t really seem to be in balance with how the man made his money or what he fought and killed for. I keep seeing comment section references to this one particular speech he made when a little black girl kissed him on the cheek, or something like that.

He leaned down and kissed the black woman on her cheek. Do you know how many people have done that for political purposes? Trump’s held black babies. He’s held Mexican babies then said he’s going to build a wall around our country to keep them out. Who cares, don’t print that shit on my [Facebook] wall!

But let’s be generous. Let’s allow, whether it’s true or not, that this version of Forrest was the real true Forrest, not the slave trader or the butcher. That’s not how he’s presenting in the park. He’s presenting as ‘The Wizard of the Saddle,’ in the uniform of an enemy the United States…

Bearing arms…

Yes, bearing arms to defend the institution of slavery — the institution that made him rich…

Riding his horse…

Yes, ‘the noble warrior.’

There was a meeting in June and we had maybe eight or nine kids from Grad Academy. And one of them said, “All my life I’ve passed that statue and thought that it must be somebody important. So when I talk about this — about how I don’t want my niece to play in the shadow of him, or turn sixteen and be driving down Union and that statue still stands. No, it doesn’t oppress you everyday. It’s not a thing everyday. But anytime it comes into your awareness it’s like that’s awful. And it’s in my city. I think if we were to pull those statues down — and I don’t care where we put them. I don’t care what happens to them, and you can print that too. If you pull them down and they turn to dust, I’m sorry. People want me to be politically correct about it, but I do not care as long as they no longer stand in the city of Memphis.What I am interested in, is what we do with that space afterwards to unite Memphians.

Oh, right. What should we do? I’ve seen so many suggestions.

I think public art is good. I think having either a contest or a bid process for people to submit proposals about unifying art. However that works. What does not represent our city in a way that uplifts a majority of Memphians is Nathan Bedford Forrest. Or Jefferson Davis either. And these aren’t hidden Parks. These are on major thoroughfares. Their placement is strategic. I think I put an MLK quote on Instagram. It was something about willful ignorance — I’ll have to look it up to get it correct. But it was basically about how continuing to argue and say ‘I don’t get how this hurts black people or how this oppresses African Americans’ is willful. And that’s my biggest concern because, even if the statues come down, the conversation continues: “Y’all are weak. Y’all let a statue bother you.” Those are things I get.

[pullquote-1] How is tearing down the icons of historic oppression weak? You take action, you capture the flag…

We took action. I can’t think, outside of Native Americans, another group of people that are told to just take it. Just take it. Deal with it. I was in Chicago talking about Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle. He talks about the waves of immigration that came into our country. Each wave assimilated and were able to uplift their heroes and remove any references to them ever having been the Negro. Right?

Like you were saying about the New York gangs, Luc Sante’s Low Life…

Think about American Gods and the waves religion that came with immigrants. Which ones stood? We still have references to Norse mythology and references even to Egyptian mythology even though we never had an Egyptian immigration wave. Where are the [other] African gods? They were destroyed on plantations in the South. I’d be crazy if I stood forth as a future political later and said I practice the Yoruban religion, right?

You would probably have difficulty persuading a key constituency.

Everyone.

Okay, everyone.

Everybody would say, ‘Okay Tami, you’ve crossed the line now.’ So I don’t think it’s just symbolic. I think it’s pushing or forcing conversations. It’s forcing a lot of people out of a lot of closets. I didn’t know we were, but now that I do I’m pushing even harder than before. Don’t just wear your Klan hood in the closet, come at me. Come out of the shadows with your racist Facebook posts Terry Roland. And lukewarm white progressives who say, “This is not a real issue,” but can’t look a black person in the face and say it.

Well, you told me we were going to talk about white fragility. And this feels like the perfect place to introduce the topic. And maybe, if we’re going to talk about that we should do it in the context of Mayor Strickland’s pushback or meltdown — His comments about all he’s done for the black community — he’s trying to get the statues down, he’s tutored a child etc. A lot of people see this and say, ‘Well, you know he has a point.’ But for me, for whatever points he may have made, the takeaway was that you and the other activists weren’t grateful enough. That seems like textbook fragility.

I’ve lost friends over this. Progressive friends. People who were like ‘Tami, you know I support you all the way. All the way to the governorship if that’s what you want.’ Now they’re like, “I’m ride or die for Strickland, and you are being unfair to this man who got a quarter of the black vote in Memphis.’ This is a man who strategically split the black vote and then goes forward to further split black people in Memphis because the photo op…

Well, it’s Memphis. It’s what we do. But whether it’s intentional or not, when you look at the last week, delegitimizing the activists does appear to be a more pressing, actionable goal for for the Mayor than getting the statues down.

It’s saying, ‘Hey .Tami Sawyer has lost her mind, these are the real black leaders. Don’t go follow that rabble rouser. Everything they’ve put out in the last month has been racially coded, straight out of J. Edgar Hoover’s media playbook.

HA! hadn’t anticipated J. Edgar showing up in the conversation…

Trump did the same thing. Take that photo back in January this year. At the time, black people are in the streets and upset about Trump’s inauguration, but Trump gets the presidents of all the HBCUs in the country to come get their picture made standing around him while he’s signing an agreement — the most basic accord. It was like, “I will support HBCUs.” There was uproar in the black community, and people were split. Some are like, we’ve got to work with him so that’s good, right? Others were like, “Why are we always selling out when we stand up against him? Well, now it’s August 2017 that was January. So, 7-months later the HBCUs are fighting for federal funding which is frozen. They’re boycotting any future HBCU summits. They’re calling for his impeachment, but what will go down in history is the photo op. So anything they may say against him now, all he has to do is tweet that photo of those 25 or 30 presidents of black HBCUs, standing at his desk smiling. Images are so powerful. We don’t even communicate in words anymore, it’s all GIFs or memes.

I’ve got to admit, I don’t even fully understand the conflict. Whatever constraints the Mayor may or may not be under in pursuing statue removal, your aim is straightforward — to take the statues down now. It was your goal yesterday, it will be your goal tomorrow. If the Mayor has a plan that MIGHT get the statues down Friday, your role isn’t to say, ‘Hooray, now this thing that hasn’t happened in the past might happen and sing “Kumbaya,” it’s to turn up the heat. Because “Kumbaya” has a pretty well documented history of failing to get the job done. Is that a fair was to characterize the dynamic?

In his mind and the minds of the people who support him, I’m an agitator and I’ve launched a revolution on Union Avenue. So he can’t be seen smiling with me at a table. But he can be seen with the historical leaders of the black community — pastors. So he goes and gets them forgetting that I’m also supported by pastors.

What do you say to people who believe he’s on your side and you’re being unfair to him? It’s not hard to see how people make the leap from, ‘He has to follow the law’ to the idea that you’re the one being unreasonable.

The law is unjust. Alan Wade said himself — said the law was built to make sure a Confederate statue was never removed in Tennessee. No other statue in the state is protected like that. Because we’re not trying to move any other statues.

And so these photo-ops, these complaints about gratitude…

What’s infuriating is using the photo to say ‘We will continue to follow the law and these people stood by and supported me and listened to me and that’s that.’ Only, the law is unjust. Alan Wade said himself — the law was built to make sure a Confederate statue was never removed. Never. And then, if you want to, we can talk about the MLK vs. Confederate argument in just a second because that’s another ridiculous argument.

Right? It’s like a swap meet. Like the things these men stood for and represented were in any way comparable.

It is.

I’ll give you Jefferson Davis in exchange for MLK and Sharpton.

Right! I’ll give you Sharpton…

If you put a blanket over Forrest.

It really is that kind of bargaining and then you have to remind them there is no MLK statue in the city where he was killed.

Well, there is a memorial on Main, on the mall. But it’s abstract — a Sphinx of sorts. It’s ramp shaped and always seems to attract more skateboarders than Civil Rights tourists.

He’s not riding a horse, I know that. Even the street names — Forest is one of the most beautiful streets in the city. It runs right behind the zoo. Where is MLK?

Underdeveloped stretch between downtown and midtown…

It’s not just Memphis. That’s a running joke everywhere. You know you’re in a black neighborhood if you see Martin Luther King Street/Boulevard. And it’s not done for racial healing or equality, it’s done to shut people up. ‘So I’m going to give the black community an MLK Street in their neighborhood and be like, ‘Have a great day.’’ But if you pull the incomes of the people who live on the street named Forest and then compare it to the income to the people who live on MLK — that’s your story.

So what does all the drama with the Mayor mean?

It means now I have to rebuild relationships and talk to folks. And we’re all focused on who was in that picture, and why, and who wasn’t in the room, and why, and who got calls and who didn’t. There was the letter showing the city had withdrawn the petition from the THC agenda in 2016, and that didn’t get any traction.There’s a whole letter from a Commissioner of the Historical Commission saying ‘This is not on us, this is on your city because in 2016 the petition was removed from the agenda and no one had attended a meeting in two years.’ And it got buried. Only one station reported on it and that was Fox 13.

And, on the subject of dividing, there was a second petition that emerged and was shared around. It was a Google doc, I think. Said something like, ‘If you REALLY support statue removal, sign this.’ Or something like that — it implied there were other things you COULD do, but this was the serious thing to do. In Google docs. But you’d already been collecting signatures via change.org for a long time.

We’ve got a letter — a petition with 4500 signatures addressed to the Historical Commission, Jim Strickland, and Governor Haslam. And we know Change.org sends notes every time somebody signs. To continuously say we need to focus on the state or the commission is to ignore what we have done that and act like we’re just out here without any direction. We did our research. So if you know that, but you won’t cooperate with us even though we’ve done the research, and we’ve found the loopholes… well? You could have let us cover the statue, instead you sent your soldiers in, like we were on a Battlefield. It goes back to the whole unjust law thing.

And if the City Council’s attorney is saying it’s easier to kill a prisoner with a lethal injection than it is to get a wavier on these statues…

And how long is Alan Wade served this city?

Can’t say right off. He’s been City Council attorney for….

Mayors come and go but Alan Wade stays right where he is. So Alan Wade sits there and tells you this. He tells the whole public, knowing what kind of media is there, knowing who’s in the room live streaming it, knowing everything he says is going to be reported. He deliberately tells you that it’s easier to kill someone with lethal injection in Tennessee than it is to remove a Confederate statue. How can you continue to say, ‘Yes, maybe we’ll follow your process’? And if Alan Wade says the statues can be covered, how do you say, ‘We don’t think we can cover the statues.’ I’m not saying Alan Wade is the Morgan Freeman of attorneys, but he’s close. And I’ll tell you, I wasn’t expecting half of what he said. I was in tears. I mean, legally our fight is being supported here.

Let’s talk about another thing that confuses people, I think — And I’m sorry for asking because this isn’t good question, but it’s one I’m seeing asked all over. What do you say to people who are like, ‘Why are you picking on the poor white mayor who’s doing all he can for you when African-American mayors like Wharton and Herenton did nothing?”

Well…

Maybe we can do a speed round of questions where you address all the terrible questions that show up in comment sections. All the ‘common sense’ questions …

Well, Wharton didn’t get them down. And Herenton didn’t get them down. I’m like, “Okay, sure, but we’re trying to do this now.” Is that stuff something we can discuss when we’re talking about the historic achievements of our former mayors? Sure it is. Absolutely. But it has nothing to do with right now, nor bearing on today and what the current Administration chooses or chooses not to do. I don’t care what Herenton and Wharton did, because I care about what we want to do right now, and if you continue to block our efforts — if you pit us against the police — if our legal observers overhear someone tell the police over the radio, “Arrest all those motherfuckers right now,” you’re not worried about what we really think. You probably wish we’d never brought the issue up, because now we’re tainting the history of your Administration. I can’t sit in a room and celebrate MLK 50 with an Administration that won’t move this statue. It’s like Supreme Court-forced busing. It’s like 70% of white kids being removed from public schools. This is like having to be sued by the NAACP to integrate with just 13 kids — kindergarteners put on the front lines. This is — I’m trying not to use the expression white supremacist because we’ve got in so much trouble for those comments. Because I’m not telling people, ‘You’re a closet racist.’ What I’m saying is, ‘There’s a bias in your awareness and in your policies.’

What you’re describing is the functional cornerstone of white supremacy though. Isn’t it? Not Nazis or extremists…

I just don’t like to use certain words. Like ‘Nazi,’ because it lets people divorce themselves from the idea that this is America and it’s happening right now, right here. Our version of hate is home-grown. It’s not about people watching what happened in Germany. It’s not about that, it’s about homegrown hate. Our supremacist hatred does not come from Germany. It come 1608, Jamestown. And on from there.

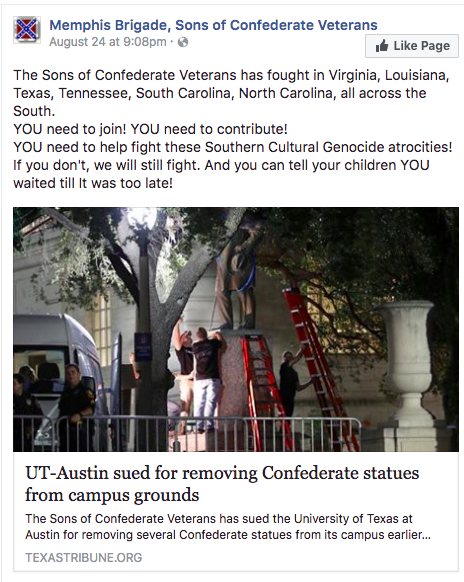

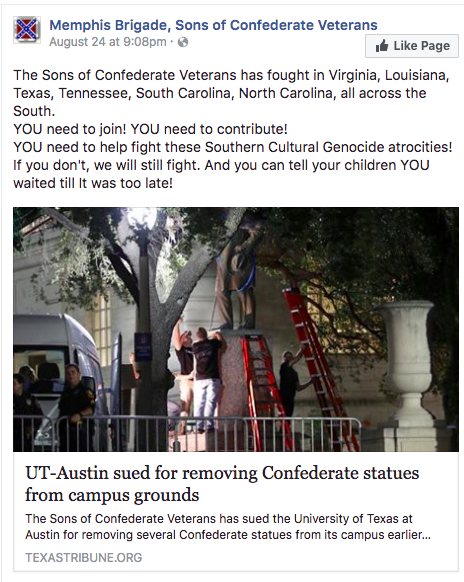

The Sons of the Confederate Veterans don’t identify as a White Supremacist group but they described the removal the statues as, and I’m quoting, “cultural genocide in the South,” and as, “A blow against the people of Tennessee.” Seems to me that defines supremacy by completely eliminating blacks and black culture from Southern culture. It’s not genocide, but it’s erasure — which is, near as I can tell, the cultural equivalent.

That’s my thing. If we’re talking about Heritage not hate, when you say this is about the Southerners’ rights, well I’m a Southerner too. My family were all slaves in Fayette County. We have the bills. We own of the land. We have the land my great-great-grandparents were slaves on. Most of the people in Memphis were slaves in Mississippi, Arkansas, and Tennessee. So saying the Confederacy is Southern Heritage and depicting Southern Heritage as being blond haired and blue eyed, doesn’t represent all Southerners. At one point there were more black people in the South than white. Until the Great Migration there were. North Carolina closed its borders to black people. South Carolina practiced Eugenics and sterilization. The black population in the South was destroyed as they saw slavery coming to an end. The zoning laws in place in neighborhoods were for the protection of white families, and not against theft and robbery — against friendship and relationships, which goes to the very homegrown fear of the white race being diluted through relations and African descendants. And here we are.

And here we are.

I said something on Facebook about, ‘Don’t tell me my heritage isn’t your heritage.’ I burn in the sun. Gayle Rose had to pull me under a tree at the protest because I was about to die. I was about to die in front of Nathan Bedford Forrest. I was red in the face and hyperventilating, and did not realize I was having a heat stroke. I sunburn as quick as any white person. I overheat. I have freckles. I turn pale in the winter. That’s violence in my blood. That’s violence in my blood. I’m not that by choice. So yeah, we share the same heritage.

So what do you tell people who think the statues are unimportant compared to poverty or other issues.

There are people who think, “You all just want to tear these statues down why don’t you want to solve for crime. Why don’t you want to solve for education? And like that. I get that from black people and white people both. But we are not one-note people. People can care about more than one thing. When I say ‘we’ I mean those of us organizing and meeting and participating. This is a multicultural fight. And it’s made up of people who are engaged in all different types of things. We’ve got Free Palestine out there with us. We’ve got our LGBTQ people. We’ve got Fight for 15 and Black Lives Matter. You can go on and on and on. You got the clergy. There was Jewish clergy, Catholic, protestant Christian clergy. White Christian, black Christian. These are people who are engaged in different things. I work in education. I work at Teach for America so my work daily is about making sure that teachers are prepared to impact their kids lives and not to further oppress or enter into classrooms as oppressors. So there’s that. I work on black economic freedom. I’m well-versed in the racial wealth gap because I’ve spent a lot of time learning about, and trying to find programs and opportunities to get on a level playing field, economically. And what that kind of thing looks like in Memphis and nationally. Social Justice. Criminal Justice.

What does it look like?

We can’t solve for Crime with more cops on the street we need to solve for crime with youth programing. My dream would be by next summer we’d be able to open a social justice camp to gets kids out of the street looking for something to do, but educational. Learning about history and their rights. Training people to be future lawyers and future Justice workers and future activists. Getting kids involved and self-advocating for themselves so, when they see what resources they don’t have, they don’t give up and advocate for their community. The teachers that have shown up and brought their students. Or come on their own are you going to tell them to go focus on education? People can care about more than one thing.

And things like crime and poverty — these are enormous abstract issues that people have been trying to solve since the beginning of civilization. Taking down the statues is so imminently doable.

Yeah, so the statues could have come down. This shouldn’t be the issue that it is. Bottom line. Should have been over.

Or, short of that, any clear, active measure by the Mayor to provide evidence of sincerity… Something people can see and understand the same way they understand what it means when you send in the police.

Let’s cover them. What makes it crazy is we keep going. And nothing. So if we can’t get these statues down, how are we going to get something done about the big issues? It’s like saying, ‘Mr. Mayor, we think there should be more money in the budget for Education,’ and hearing, ‘No, sorry, that’s grandstanding. You should have told me 2-months ago you wanted money for education.’ We’ve decreased the education budget by $65-million and we’ve increased policing by $75-million. And I don’t know what that’s resulted in except for more black and brown kids in jail. You know “tough-on-crime,” and “Fed Up,” well, it doesn’t work. It doesn’t. Building more prisons than schools doesn’t work. You take 18-years away from somebody’s life and then you put them back on the street? My formative years were spent figuring out what it meant to be adult between the age of 18 and yesterday. What if I had to do that in prison for some petty crime? What would I be to society when you let me go? We’re locking kids up at 12 and keeping them for years and expecting them to come home and be a part of a community. Somebody that was locked up 15 years ago missed the advent of the iPhone. You hand them a smartphone and they’re like, ‘Oh can I call you at home?’ I haven’t had a house phone since 2004. Technology moves so fast causing whole populations of black and brown youth to miss out on being able to support and advance their communities. It goes even further. Think about marriage. They talk about black love and why the average black woman has a higher degree, or better job than black men. This is why. Because black men getting arrested for petty crimes and getting 18 years.

When people think of white supremacy they think of the Klan burning crosses and Neo-Nazi skinheads and all the extreme examples. But isn’t it fair to characterize all of this that you’re describing here as how white supremacy actually works?

People say, ‘Well I’m not personally white supremacist.’ We’re saying, ‘But wake up. You’re living out white supremacist structures that continue to oppress, subvert, destroy, and destruct a whole culture.’

Ekundayo Bandele

Ekundayo Bandele

JB

JB  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks