Yes, that’s “Confederates in the attic” you’re hearing now, but it’s the living who are rattling their chains, a ruckus caused by our lack of understanding of the past. Like many Southern cities, Memphis is wrestling with ghosts these days.

One of ours is Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest, whose bronze likeness sits atop a horse in Health Sciences Park. Calls to remove the statue have sparked controversy, but they shouldn’t. Defenders of the site today seem to have forgotten who Forrest was, why the tribute was put there in the first place, and even the purpose of monuments generally.

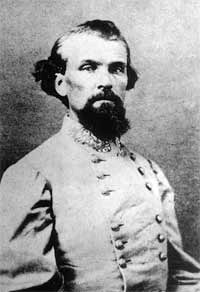

Nathan Bedford Forrest

According to historian Charles Royster, Forrest “was a minor player in some major battles and a major player in minor battles.” But he was also responsible for the massacre of black soldiers at Fort Pillow, an atrocity that drew widespread condemnation all across the country. Before the war, Forrest trafficked in slaves and acquired a “notorious” reputation even within his home state, and he helped found the Ku Klux Klan, the nation’s oldest continuing terrorist organization.

His memorial was completed in 1905, a time when the South was reclaiming its connection to the Lost Cause and trying to rehabilitate its military leaders, and doing so while redoubling efforts to subjugate African Americans through segregation, discrimination, and violence. The two things were closely connected. After all, this was the heyday of lynching. Yet those defending Confederate statues seem keen to ignore or minimize that part of the past.

Many people refer to these artworks themselves as history. But they’re really statements about history. And sometimes we get these salutes wrong or change our minds or rethink what we once thought. Sometimes we learn things about the individuals commemorated in these tributes that make them embarrassing or worse. But if you insist otherwise, follow your own logic: If erecting a statue is history, then so is removing it.

Would you have told the Hungarians not to remove the statue of Joseph Stalin in 1956? Were they erasing history? Whitewashing the past? Hardly. The people who launched the uprising that fall were attempting to overthrow a Soviet puppet regime that oppressed them, and having to stare at the symbol of that oppression was an insult too great and grievous to bear.

A colleague of mine recently compared monuments to books in a library — some good, some not, but would you really want even the disreputable ones taken off the shelf, he asked? Actually, yes. Librarians cull their collections all the time. So although his argument may at first sound persuasive, the analogy is wrong. Monuments aren’t books. They’re brands, publicly endorsed and often supported. They enjoy a prominence not easily escaped and a validation not easily denied.

It’s easy to show equanimity or insouciance when you’re not a member of a group that’s been terrorized. It’s easy to say, even with the best of intentions, that monuments to villains are a way to remind us of where we’ve been and how far we’ve come, and “wouldn’t it be splendid if we just used them as a history lesson.” Yet no one would expect Jews to tolerate a statue of Joseph Mengele in a nearby park. Or Catholics to put up with a statue of Queen Elizabeth.

It’s true that almost all historical figures have their detractors, but why preserve monuments to people who actively tried to vanquish whole groups? Why salute individuals with murderous or genocidal reputations?

There are alternatives. Plenty of Americans — North and South, black and white — brought us together. Pay tribute to them.

In the meantime, pack up these old Confederate statues and put them in museums. They don’t deserve to adorn city spaces in the 21st century. Not only do they fail to represent all of us, but these vestiges of apartheid are opposed to and stand as a painful affront to many of us. They may be a “heritage” in the sense that they have been passed down from ancestors, but some things we inherit turn out to be oddities we’d rather keep in the attic than hang in the dining room.

It works the other way, too. Some things we once celebrated, such as the Forrest statue, obscure ugly truths. As historian Jacquelyn Dowd Hall has written, “Remembrance is always a form of forgetting.” It is a means of coping, too, of trying to make peace with the past and with oneself. That’s the reason we create heroes, memorialize them, and sometimes scorn and eventually replace them.

Ghosts don’t haunt us, it turns out. We haunt them.

Joe Hayden is a historian and a professor of journalism at the University of Memphis.