As Memorial Day approaches and we pay homage to men and women who made the ultimate sacrifice in the line of duty, it’s also worth remembering other fallen heroes. And for this writer, Memphis music has produced no greater hero than Phineas Newborn Jr., the pianist who grew up playing Beale Street in his father’s band, then conquered the world with his transcendent talent.

At least, he should have conquered the world. Despite any acclaim he garnered amongst jazz afficionados in his heyday, he was, in his latter years, a supremely troubled human, struggling with the most pedestrian aspects of life in Memphis, a figure typically written off by the well-to-do passing him by on the street. Which made his supreme artistry on the ivories all the more heroic. (Read Stanley Booth’s masterful and poignant portrait of Newborn’s contradictions, the chapter “Fascinating Changes” in his anthology, Red Hot and Blue: Fifty Years of Writing About Music, Memphis, and Motherf**kers, and you’ll see what I mean.)

With Sunday, May 26th, marking the 35th anniversary of Newborn’s passing, this Memorial Day weekend will be an excellent occasion to honor his life and work.

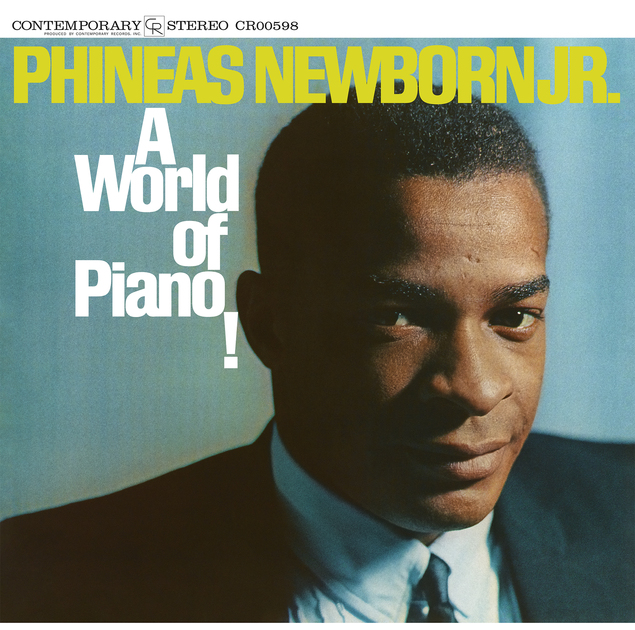

You can find no better starting place than his 1962 platter, A World of Piano!, first released on Contemporary Records, now available as part of Craft Recordings’ Contemporary Records Acoustic Sounds Series, featuring lacquers cut from the original master tapes (with an all-analog signal path) by Bernie Grundman, a Grammy-Award-winning engineer who once worked for Contemporary when it was one of the hippest labels in the country. Craft’s reissue, released on 180-gram vinyl last December, is a sonic marvel.

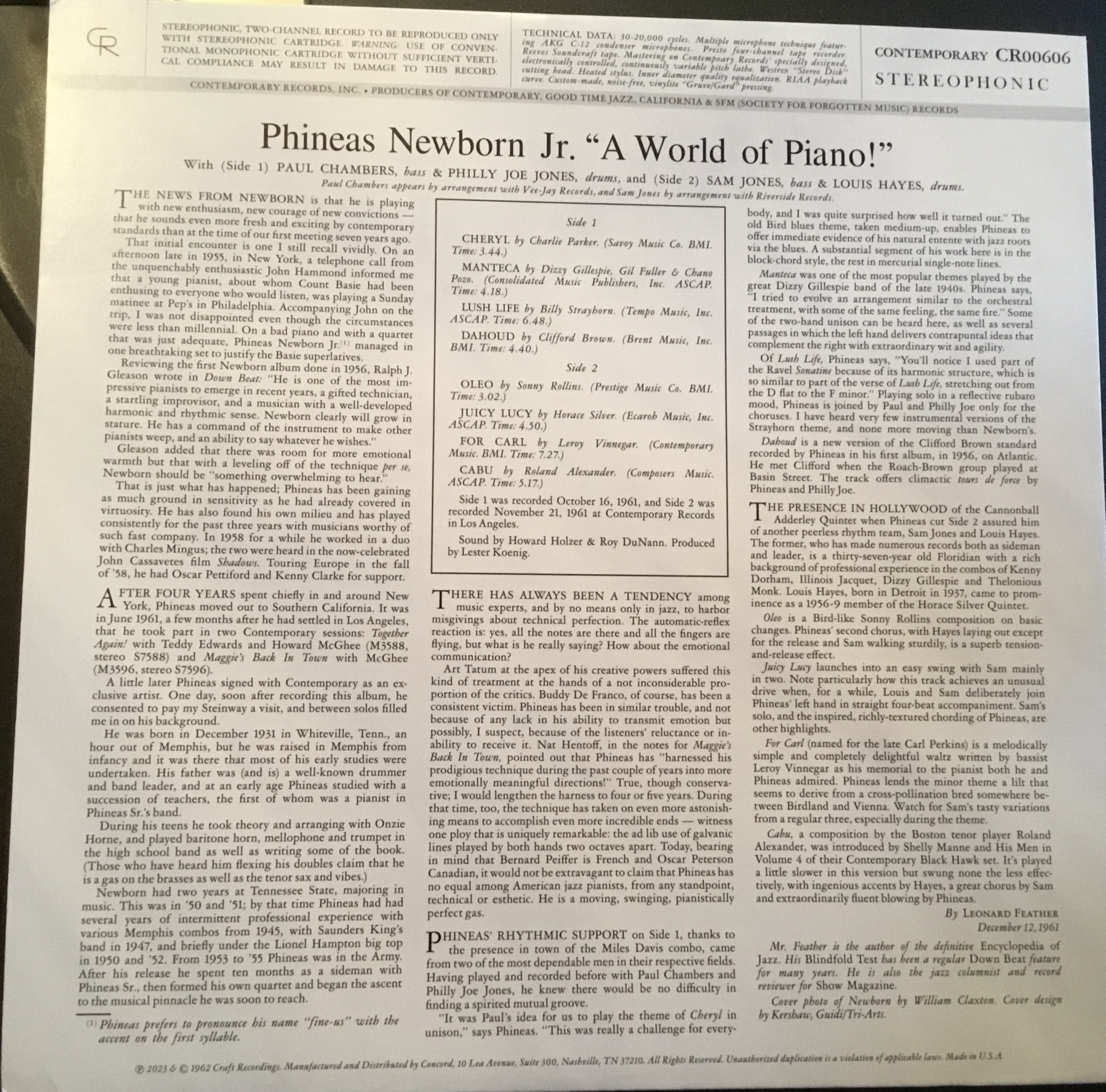

It’s also a visual marvel. Unlike many reissues which tweak the album art of classic platters, or, worse, try to update the art altogether, this and the other releases in Craft’s Contemporary Records Acoustic Sounds Series pay complete fealty to the aesthetics of the original records. This means that the full experience of the album is in your grasp, right down to the brilliant liner notes by one of the legendary practitioners of that art (and another personal hero), Leonard Feather.

An accomplished musician and composer in his own right, Feather digs deep in these notes and offers the reader some powerful insights. The notes are a tome unto themselves; when was the last time you saw liner notes with footnotes? Better yet, in the first, Feather notes a telling detail that’s usually only acknowledged by Memphians: “1. Phineas prefers to pronounce his name ‘fine-us’ with the accent on the first syllable.”

Feather’s learned approach is in dialogue with Newborn himself. The notes read: “Of ‘Lush Life,’ Phineas says, ‘You’ll notice I used part of the Ravel Sonatine because of its harmonic structure, which is similar to part of the verse of ‘Lush Life,’ stretching out from the D flat to the F minor.'” Who else but a pianist and musicologist would elicit this quote from the virtuoso?

Indeed, the version of Billy Strayhorn’s classic tune here is a dazzler, and, given Newborn’s sheer dexterity and rapid-fire playing elsewhere, beautifully restrained. All Ravel interpolations aside, this is exquisitely sparse, letting Strayhorn’s melody shine in the first iteration, the drums and bass not entering until the chorus begins. This “Lush Life” is a revelation in its simplicity.

Other tunes, like opener “Cheryl,” display Newborn’s fireworks to the utmost, played with a ferocity that caused me to sit up at attention when I dropped the needle. Yet other tracks display the sheer groove of Newborn’s playing, as with the pounding Latin rhythms of “Manteca,” one of Dizzy Gillespie’s signature tunes, here somehow evoking a full horn section with only Newborn’s chordal blocks, hammered as if on a timpani.

“Juicy Lucy” offers a master class in swing, simultaneously lilting, playful, and sultry, while “For Carl” is the epitome of that lost art, the swing waltz. The swaying, 3/4-time number was, as Feather notes, “written by bassist Leroy Vinnegar as his memorial to the pianist both he and Phineas admired” — the one and only Carl Perkins. Actually, strike that…this guy had nothing to do with “Blue Suede Shoes,” so he should be dubbed the also and other Carl Perkins. Yet fully worthy of this beautiful homage, nonetheless.

The grooving is mutual all around, as Newborn finds himself complemented with some of the greatest rhythmists of his time. As Feather’s notes make clear, this was due to the happenstance of Newborn being in Los Angeles for these recording sessions as other bands passed through. Side One swings like it does “thanks to the presence in town of the Miles Davis combo … Paul Chambers and Philly Joe Jones,” Feather writes, later noting “the presence in Hollywood of the Cannonball Adderley Quintet when Phineas cut Side 2 … Sam Jones and Louis Hayes.”

Such details, along with the masterful reproduction of this album in its original form, put you in that time. Yet it’s not nostalgia that’s summoned up, but the immediacy, the vibrancy, and the modernity of that era. Thanks to Craft Recordings, you can now hold some of that bottled magic in your hands.