How To Talk About Books You Haven’t Read

By Pierre Bayard

Bloomsbury, 208 pp., $19.95

Is Pierre Bayard serious?

You may find yourself asking this question frequently as you read his polemic, How To Talk About Books You Haven’t Read. The first line of the opening section, “Ways of Not Reading,” is: “There is more than one way not to read, the most radical of which is not to open a book at all.” Bayard then proceeds to enumerate the various ways you can learn to fake it in literate company. And, he posits, the literate company may be faking it, too.

Before I read this little book I thought it was going to be a smartass, albeit intellectual (Bayard is a professor of French literature in Paris, and the book is translated from the French … well, you understand) humorous caper, à la David Sedaris. It might please Bayard if I reviewed it under that misapprehension, since he doesn’t prize finishing, or even reading, a complete book. Or so he says. The irony is, of course, that you are reading about not reading, which is — we can only assume — part of Bayard’s jape, if jape it is. The thing is, he sounds serious.

He writes, “Between a book we’ve read closely and a book we’ve never even heard of, there is a whole range of gradations that deserve our attention.” He then questions what we mean by the term “reading.” Later he writes, “When we have a book in our hands, it is rare that we read it from cover to cover, assuming such a feat is possible at all.”

What? you ask. Is he serious?

Bayard makes some breezy, some highbrow points about the way our culture relates to books. Some of the arguments are sardonically funny. He recommends skimming. He illustrates using some curmudgeonly writers, who also groused about reading. He quotes from the movie Groundhog Day. (Actually, he misquotes the movie … is it possible he only skimmed watching it?) By taking his exaggerated — possibly tongue-in-cheek — stance perhaps Bayard’s plan is to drive more people to reading. Is this his “Modest Proposal”?

How To Talk About Books You Haven’t Read can be boiled down to a simple premise: We still live in a culture that values the reading of books, or at least the discussion of the reading of books. So, it would be helpful if one could learn to discuss books without the burden of having to actually read them.

That’s it in a nutshell. You decide whether he means it. And, since I’ve just given you a thumbnail, you don’t have to read this book, either. You don’t even have to say forgive me, father, for I have skimmed.

Seriously. — Corey Mesler

The Letters of Noel Coward

Edited by Barry Day

Knopf, 753 pp., $37.50

Noël Coward’s life and work are too complex to be described easily, and yet the following might do the trick: After attending the 1972 opening of the musical revue Cowardy Custard (with Marlene Dietrich on his arm), Coward observed, “One does not laugh at one’s own jokes, but I walked out humming all the tunes.”

The Letters of Noël Coward tells the fabulous story of the man known as “Destiny’s Tot” in his own fabulous words as well as the words of his equally fabulous correspondents. In fact, if this handsome, chronologically arranged collection has a hair out of place, it’s because it carries more “darlings,” “dearests,” and “little lambs” than can be humanly tolerated. Remove the terms of endearment, and this large edition shrinks to a more manageable volume in nearly every sense.

Jovial self-importance aside, there are reasons why Coward, the beloved actor, gifted entertainer, prolific playwright, witty composer, and competent novelist is so often called “The Master.” He was a soldier (albeit a bad one), a spy (of sorts), an unparalleled wit, and an indisputable man of his time. Coward became the prototype for the modern celebrity, an individual famous for being famous. All of this territory is covered in his letters. Coward’s vast and ever-widening circle of letter-writing friends included many of the most interesting and important personalities of the 20th century. His pen pals ranged from radical feminists to the Queen Mother and included Churchills, Roosevelts, George Bernard Shaw, Virginia Woolf, Alexander Woollcott, Greta Garbo, and Laurence Olivier.

As a compulsive world traveler, Coward’s missives from abroad are brilliantly English in their palavering over beautiful vistas and their complaints about the beastliness of regional cuisines. But The Letters of Noël Coward is at its best on the rare occasions when the wit falls away, allowing the reader to see a cruder, less self-assured character than the man Michael Caine once described as a bit like God.

When not swapping well-turned barbs with David Niven and Alec Guinness or imploring Dietrich to eschew l’amour, Coward mulls over the fact that his stylishness and gift for dialogue are more a curse than a blessing and that he wrestles with the difficult task of plot and character development. Contemporary writers, take note.

Tightly edited and with pointed commentary by Coward on Film author Barry Day, the The Letters of Noël Coward is a deliciously light read that painlessly morphs into a history of the 20th century.

— Chris Davis

The Gathering

By Anne Enright

Black Cat/Grove Press, 260 pp., $14 (paperback)

“I would like to write down what happened in my grandmother’s house the summer I was eight or nine, but I am not sure if it really did happen. I need to bear witness to an uncertain event.”

Thus begins Anne Enright’s novel The Gathering, announcing immediately that we are in the hands of an unreliable narrator. Suspicious of her own memories and swayed by family allegiances, Veronica Hegarty, one of an untold number of siblings in a middle-class Irish family, struggles to record the history of her parents and grandparents, as well as her own childhood. The death of her older brother Liam, possibly accidental but most likely a suicide, motivates her narration, but her grief colors her recollections.

Unreliability can breed fascinating narrators, such as Humbert Humbert in Lolita or anyone in Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury, but unfortunately, Veronica is, in addition to being unreliable, also long-winded, dull, detached, and aloof but not in ways that are compelling or even all that interesting. Hers is not pleasant company to share for 260 pages. There is a kernel of a good and potentially satisfying work of fiction here, but writing in Veronica’s voice, Enright buries it under too many tricks as she protracts scenes over several chapters and moves the novel along at a glacial pace. For example, early in the book, she describes two characters sitting in an empty hotel lobby, each trying not to acknowledge the other. It’s a telling scene for two or three pages, but at more than 20, it’s more like a literary parlor trick than a stalled confrontation.

Enright weighs down the story in abstruse prose that favors abrupt cuts between scenes and the bluntest symbolism imaginable, as in: “If you ask me what my brother looked like after he was dead, I can tell you that he looked like Mantegna’s foreshortened Christ, in paisley pajamas.” Beyond that, The Gathering relies for impact on statements that sound enormously profound but are, once you delve below the surface, ultimately meaningless. For instance, reminiscing about her dead brother, Veronica writes, “I do not think we remember our family in any real sense. We live in them, instead.” On first read, these two sentences sound reasonable and perhaps even poignant; they’re evasive, certainly, as if to provoke thought, but such reflection only reveals how empty Enright’s words are.

These ineffective devices, of course, could be the product of Enright’s unreliable narrator, a keyhole through which to peek at her fractured psyche. But that’s too easy, too excusing. Certainly, Enright conveys Veronica’s angst very clearly, but the character takes no action other than to write and to shrug her shoulders. Occasionally, she hangs up on her siblings, who never surpass their function as annoyances to become flesh and blood characters. Veronica simply writes it all down, as best as she remembers, making the reader an audience to her self-therapy. It doesn’t help. Veronica never changes but simply reveals how badly damaged she is and how her family made her that way. Memories become a means of self-justification; they explain Veronica’s detachment, sure, but they also allow Enright too many indulgences. That this overwritten, underthought novel won this year’s prestigious Man Booker Prize only shows what a bad year it’s been for British fiction. — Stephen Deusner

The Holiday Season

By Michael Knight

Grove Press, 193 pp., $18

If it’s good cheer you want in your reading this holiday season, skip The Holiday Season, Michael Knight’s new double set of novellas — the first, called itself The Holiday Season; the second: Love at the End of the Year. But if it’s good writing plain and simple you seek, see here: The season that can bring out the best in individuals can bring out the worst — old wounds, new fault lines — in most any family.

Take the Posey men in The Holiday Season. That’s Jeff Posey, a retired lawyer and former city councilman in Mobile, but the wear and tear on him (and his house) after the death of his wife are beginning to show. He’s a no-show, however, at Thanksgiving at the home in Point Clear of his lawyer son Ted, then he’s a no-show at Ted’s at Christmas. Ted, for his part, won’t budge. It’s time his father visited Ted and his family for the holidays. This leaves it up to 33-year-old Frank to see to his lonely, disgruntled father’s welfare on Thanksgiving and to observe his brother’s signs of success — appealing wife, adorable twin daughters, nice house — on Christmas Day. What Frank should be seeing to, however, is his stalled career as an actor. Nothing earth-shattering here. Just crystal-clear prose of the sort that’s easy to admire, hard to achieve.

Love at the End of the Year? That’s a more complicated, messier matter than Thanksgiving or Christmas, because it’s time to take stock and maybe (or maybe not) make a fresh start. Katie Butter’s ready to leave her husband but doesn’t. Lulu Fountain’s ready to leave home, at age 13, which she does, then doesn’t. And Esmerelda Diaz is ready to call the dating game quits, because she doesn’t have a guy to kiss at a New Year’s Eve party. Even she, though, has second thoughts as the night wears on (and her panties come off). And what of Stella Fountain, Lulu’s divorced mother, who’s been through the ringer already this brand-new New Year? She’s willing to acknowledge that the world’s a perilous, random place — nothing more, nothing less, and true enough. — Leonard Gill

Michael Knight — Alabama native, director of the creative writing department at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, and a former John and Renée Grisham Emerging Southern Writer at the University of Mississippi — will be signing The Holiday Season at Burke’s Book Store on Monday, December 3rd, at 5 p.m. and at Square Books in Oxford on Thursday, December 6th, at 5 p.m.

The Conscience of a Liberal

By Paul Krugman,

Norton, 296 pp., $25.95

If there is a reason why Paul Krugman, an economist, an academician, and a denizen of Princeton, not Washington, is arguably the most influential political theorist of our time, at least on the left, it is an ironic one. In the pathfinding New York Times columns he has written since 2000, Krugman has inverted a shibboleth that has governed both economic and political thinking since the time of Marx, nay, since that of Adam Smith.

The supposed truism Krugman renders false in The Conscience of a Liberal is that economic reality precedes political change. In our time, the theory would attribute a resurgent inequality of incomes to the advent of technological change, which has skewed the distribution of wealth to a new non-manufacturing elite. And even Krugman pays a sort of homage to the idea with a characteristically choice sentence: “If Bill Gates walks into a bar, the average wealth of the bar’s clientele soars, but the men already there when he walked in are no wealthier than before.”

But Krugman sees a different reality — that “movement conservatism,” birthed in Republican Party politics via such disparate forefathers as Barry Goldwater, Ronald Reagan, and William F. Buckley, began to attain political power in the ’70s and thereafter transformed the economic sphere through pure ideology. In the process, he argues, society and politics have drifted further and further from bipartisanship, and the role of an ever-weaker middle class has been correspondingly diminished.

The achievement of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal had been what Krugman calls a Great Compression, equalizing incomes through the tax and social policies of an activist government. But, goes Krugman’s thesis, the elitist politics of the last few decades has capitalized on an existing racial divide and other social fears to reverse such policies and bring about a new Gilded Age in the interests of a small but disproportionately prosperous economic elite. The result is the oft-cited reality that the American safety net has shrunk, especially when compared to the social structures of other industrialized nations.

Krugman’s proposed remedy to this new economic stratification is a politics re-infused with social conscience. Hence the title of his latest book. Embracing the out-of-fashion adjective “liberal,” he notes: “One of the seeming paradoxes of America in the early twenty-first century is that those of us who call ourselves liberal are in an important sense conservative, while those who call themselves conservative are for the most part deeply radical.”

The Conscience of a Liberal is both a call to arms on behalf of this idea and an indispensable primer on the new economics of inequality, which, Krugman argues convincingly, has begun to erode constitutional liberties and adversely affect foreign as well as domestic policy. — Jackson Baker

How the South Joined the Gambling Nation: The Politics of State Policy Innovation

By Michael Nelson and

John Lyman Mason

Louisiana State University Press, 261 pp., $35

The art of state politics is less interesting than insiders think it is and more interesting than outsiders think it is.

This is a problem for the dwindling number of reporters who watch the business of state legislatures unfold day after long day. Their employers long ago recognized that lawmaking no longer equals news. And it’s a problem for scholars who try to tell us what it all means minus the personalities, suspense, gossip, and boozy camaraderie of the Capitol Hill crowd.

Michael Nelson, Fulmer Professor of Political Science at Rhodes College, and his former colleague John Mason have put together a very readable summary of how gambling came to seven Southern states, including Tennessee and Mississippi. But they may have a hard time attracting general readers to a story they already know in broad outline or do not care to know. Many of the events described took place before 2004, and Nelson and Mason previously wrote about them in an academic publication.

There are fresh insights about the Tennessee lottery and the Mississippi casinos, and readers with a political bent will be rewarded even if they read nothing more than those chapters and the summary and introduction. Nelson did several of his own interviews for these chapters, and he writes as well as the best journalists. He pays close attention to former Tennessee senator Steve Cohen in particular, giving him mixed marks and this zinger:

“Indeed, some [antigambling] funds were spent developing a campaign plan that accomplished something previously unknown in Tennessee politics: it made Cohen a sympathetic figure.”

If the whole book were written in that vein, it would have broader appeal, but most of the players are one-dimensional mouthpieces instead of the living, breathing, maddening, wavering, joshing characters they are — or at least were in their 15 minutes of fame.

Timing is another problem. The Tennessee chapter ends before Cohen makes his successful run for national Congress and before Chris Newton, the House co-sponsor of the Tennessee lottery bill, takes a fall in Tennessee Waltz.

The news from Mississippi is even older. Casino legislation passed in that state in 1990. But Nelson puts it in perspective and updates it with the impact of Hurricane Katrina on the Gulf Coast and crooked lobbyist Jack Abramoff on the Choctaw Indian casino. And, as far as I know, he is the only writer to recognize the importance of eliminating the single word “underway” from the original legislation. That meant that riverboats didn’t have to move, and that is why Tunica today looks the way it does. — John Branston

Cleopatra’s Nose: 39 Varieties of Desire

By Judith Thurman

Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 427 pp., $27.50

For those obsessive about their bookshelves, filing Judith Thurman’s Cleopatra’s Nose may pose a problem. This collection of well-crafted essays, profiles, and book and art-exhibit reviews — most of which originally appeared in The New Yorker — covers a broad range of subjects, from fashion designers and fashion plates to tofu makers and performance artists. (There’s even a coda, of sorts, on job titles and their 31,000 varieties in the last essay — the 39th of the 39 “desires” of the subtitle.) My advice? Put Cleopatra’s Nose with the rest of your books about culture and be done with it. More than likely after working through Thurman’s impressively exhaustive writing, you’ll be impressively exhausted.

Thurman’s specialty is taking on the most fascinating creators of style and mood and moment — be it Bill Blass or Anne Frank or Irving Penn or Teresa Heinz Kerry. But that feeling of fatigue begins with an introduction that endeavors to explain the book’s title (confusing) and throws in a bit of awkward autobiography with details of the author’s difficult mother (even more confusing). A reader’s patience is further tested with the first profile — nearly 20 pages on a beautiful, bulimic Italian performance artist whose art openings consist of naked or nearly naked emaciated models mingling among clothed and regularly proportioned guests, scenes that read like the very definition of the culturally tired.

But there’s substance to this work, and lots of it. Thurman’s account of the ancient art of kimono-making in Japan is illuminating, and her musings on Marie Antoinette, written to coincide with Sofia Coppola’s biopic, provide sympathetic weight to a woman doomed by her frivolity.

Thurman has an eye for context and the courage to write critically. While the topic of culture may seem relatively unimportant in the larger scheme of things, Thurman proves otherwise, demonstrating how a frock or a simple turn of phrase can shape history. — Susan Ellis

The Complete Book of Aunts

By Rupert Christiansen with Beth Brophy; illustrated by Stephanie von Reiswitz

Twelve, 242 pp., $19.99

Since before my younger sister was even out of kindergarten, probably around the time my Aunt Patricia got married, we both decided that we wanted to be “the cool aunt.” There was one flaw. If both of us were planning to be the cool aunt — an aunt who is normally childless — neither of us was going to get to be any type of aunt.

Luckily, two solutions presented themselves: my younger brother and then my youngest sister. But such is the power of the auntie.

The Complete Book of Aunts taps into this power and attempts to explain not only the who’s and why’s of aunthood but the history as well. Apparently, some cultures don’t recognize aunts (a shortcoming in the authors’ opinion), while others distinguish between aunts on the mother’s side, aunts on the father’s, and aunts who are your parents’ friends.

The book, modified for American readers from a British edition, classifies aunts into several categories: mothering aunts, eccentric aunts, X-rated aunts, brand-name aunts (think Jemima), and more and gives examples of each.

Victorian literature has perhaps more than its share of aunts — where you have orphans, you have aunts — and that tradition continues to the present day. Harry Potter, for instance, suffers his Aunt Petunia’s house in the summer. The evil aunts in James and the Giant Peach are squashed when the peach rolls over them. Then there is Auntie Mame, Auntie Em, Aunt Bee, and a gaggle of other aunts lurking in popular culture.

I am an aunt myself now, though I’m not sure if I would classify myself as a cool one. (And if I said I was the cool one, I’d hear from my sister.) In fact, I’m not sure what type of aunt I am. At least I haven’t been run over by a giant peach. Not yet anyway. — Mary Cashiola

Borat: Touristic Guidings to Minor Nation of U.S. and A. and Touristic Guidings to Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan

By Borat Sagdiyev

Flying Dolphin Press, 176 pp., $24.95

It’s odd for a Borat book to come out now, over a year since the film it’s based on — Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan — was released, to great critical and commercial success. But it’s just as well. As literature, the movie/book tie-in is not usually at the top of the literary food chain, and since the Borat book is, at times, every bit as funny as the film and infinitely better than most tie-in lit, a break from convention is appropriate.

Though the film was structured as a travelogue, Borat on the page looks more like a textbook. In it, a double-sided tome with U.S. and A. working toward the middle from one end and Kazakhstan from the other, Borat explores the two countries, each written for an audience of outsiders.

In the Kazakhstan section, for instance, you’ll learn that in 2003, “Tulyakev Reforms is announce meaning that women can now travel on inside of bus, homosexuals no long has to wear blue hats and age of consent is raise to 8 years [most definitely sic].”

This is typical of the humor at work here: awash in racism, misogyny, homophobia, anti-Semitism, and just about every other offensive perspective you can name. It’s so extreme it would be very difficult to miss the sarcasm (one hopes). Appropriately, the book’s production values are quite low, and Borat is the Remembrance of Things Past of broken-English jokes.

Interestingly, in missing out on one of the biggest thrills of watching Borat the film — knowing that actor Sacha Baron Cohen did it all, with a straight face, in front of strangers — Borat the book taps into something greater than great comedy. The film wrung from audiences lots of yucks and a good bit of schadenfreude by watching innocent-bystander (and some not so innocent) responses to Borat, but the outrage was at least one remove from the viewer. With the book, it’s just you and Borat there in your comfy chair and nothing between you and the offense you’ll undoubtedly take at what you see and read. And that’s a good thing. — Greg Akers

Nobody Likes a Quitter (And Other Reasons To Avoid Rehab): The Loaded Life of an Outlaw Booze Writer

By Dan Dunn

Thunder’s Mouth Press, 240 pp., $14.95 (paperback)

I’m jealous. While I spend my days as a Flyer staff writer poring over documents or conducting interviews for hard news stories, wine and spirits writer Dan Dunn is boozing it up with publicists from some of the world’s top liquor industries. That’s what Dunn considers research for his weekly column “The Imbiber.”

Dunn pens the column, with content ranging from reviews to cocktail recipes, for Metro International Newspapers. It’s a job that sounds too good to be true. While many alcoholics end up begging for change on street corners, Dunn actually gets paid to drink for free.

Nobody Likes a Quitter is a humorous look at how Dunn went from a life of coke-snorting and couch-surfing in Aspen, Colorado, to living the booze-writer life filled with all-expense paid trips to investigate the latest in European drinking habits.

Dunn’s slice-of-life memoir, un-ironically arranged in 12 steps rather than chapters, is spiked with celebrity run-ins (he was close friends with Hunter S. Thompson), cocktail recipes (try the “Fucked by a Rockstar”), and the history of top-name liquor brands. Just in time for the holidays, Dunn also offers a guide to giving the gift of liquor in “What Would Jesus Drink? A Holiday Hootch Guide” in Step 10.

In the opening author’s note, Dunn calls his book “a mosh pit of fact and fiction” and warns readers that parts of the book are entirely made up. When you stay liquored up, you can’t be expected to remember enough to piece together a whole book. In Dunn’s words, his “memory is foggier than a San Francisco morning after a Grateful Dead show.”

I found the mixing of fact and fiction to be a little annoying, however. I mean, how will I ever know if Dunn shared pomegranate martinis and cocktail weenies with Charo, Chaka Khan, and Cheech Marin?

I also found it hard to resist sampling Dunn’s cocktail recipes while reading Nobody Likes a Quitter, which means I often woke up to find myself in a pile of vomit, book still in hand. I’m not sure I’ll ever get the stains out of the pages.

Okay, I may have made that up. But Dunn’s book does tend to inspire the inner alcoholic. Too bad the rest of us have to pay for our drinks. But ah, if only we could all be so lucky! — Bianca Phillips

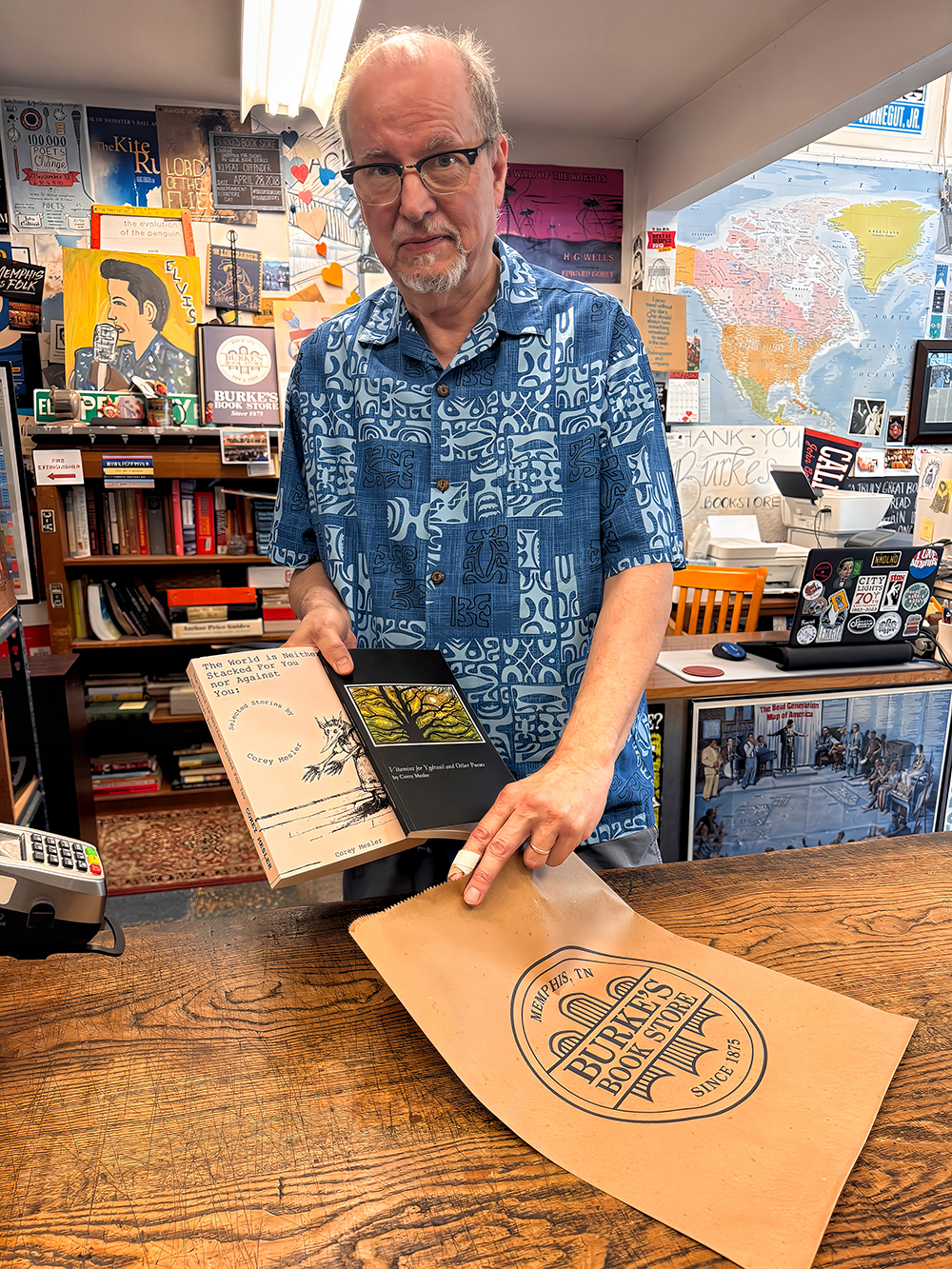

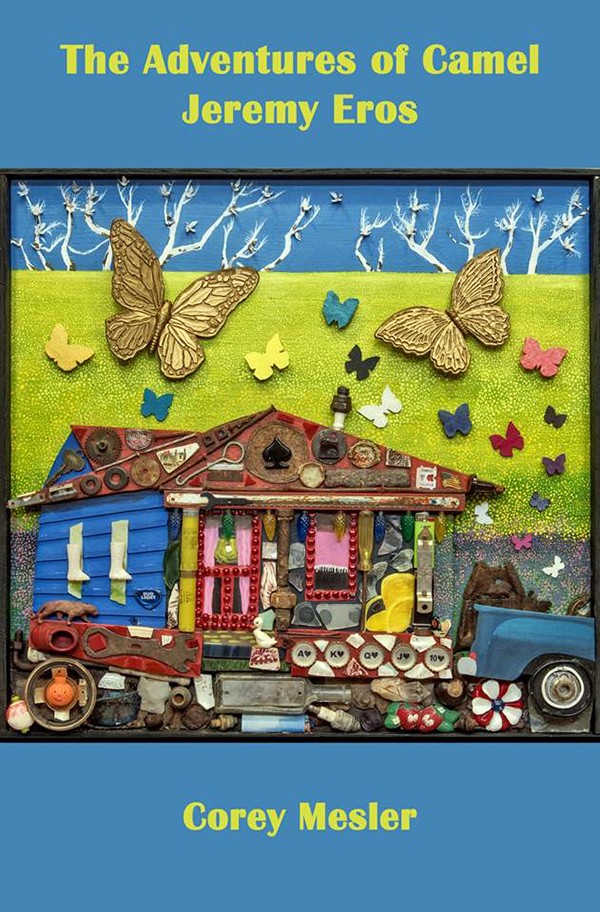

Courtesy Corey Mesler

Courtesy Corey Mesler

Sandra McDougall-Mitchell

Sandra McDougall-Mitchell