You may not notice a difference. The 6 p.m. and 10 p.m. news anchors probably won’t change, so faces will remain as familiar to viewers as the tried-and-true news/weather/sports format. Automation may result in lost jobs on the production side, but broadcasts will look slick, with fast editing and eye-catching visual content. But whether you notice differences or not, TV news in Memphis is in the midst of an unprecedented and abrupt shakeup that started in January, when Gray Television completed its $3.6 billion dollar acquisition of Raycom Media Inc. That deal made NBC-affiliated WMC-TV, the first of Memphis’ local TV news stations to change ownership this year. It was a harbinger of things to come: Barring unforeseen delays, each of the city’s five TV news channels will be under new ownership before the start of 2020.

Viewers are more likely to associate local stations with CBS, NBC, or Fox, than their parent companies, but nationally branded network affiliation and ownership aren’t related. There’s no reason to expect viewers checking in to see if it’s going to rain or if they’ve won the lotto to recognize the names of remote corporations controlling their local news. So please bear with me while I fill out a game bracket.

CBS-affiliated WREG, now a Tribune property, will soon belong to the Nexstar Media Group. Nexstar is already the second-largest owner of local TV stations in the country, and before the $4.1-billion Tribune merger can happen, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) wants Nexstar to sell some properties. Two of the 19 stations Nexstar is unloading are WATN and WLMT, an area duopoly collectively branded as Local Memphis. Local Memphis was picked up by Tegna Inc., a media/marketing services group created in 2015, when Gannett, The Commercial Appeal‘s corporate owner, split into two separate publicly traded companies. Meanwhile, Fox 13, now owned by Cox Media Group, a subsidiary of Atlanta’s Cox Enterprises, is being absorbed into Terrier Media, a division of the private equity group Apollo Global Capital. Got all that?

So why all the sudden change, and what does that mean for “the viewers at home”? These are the questions that matter, of course. But before going there, let’s back up and take in a broader media landscape. Newspapers, which were identified in a 2012 FCC report as providing much of the available information required for a healthy democracy, are shrinking. Many papers — weeklies, primarily but metro dailies, too — are shuttering altogether.

The story you’re reading is the second in a series of Memphis Flyer cover packages cumulatively addressing “information justice.” The first installment, “Going to Pieces,” focused on Memphis print media’s struggle in a fractured, increasingly digital market, and how that struggle trickles down to consumers. That story also attempted to change how we talk about “media,” looking behind the usual industry myths and political narratives to see how news content is mostly determined by economics. This is relevant for context, but also because, as reported in The Expanding News Desert — a study published by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC) — the more local and regional newspapers shrink or disappear altogether, the more important local TV news becomes. Between accessibility and sustained profitability, TV is well positioned to “fill the news void.” But will it?

Penelope Muse Abernathy, author of The Expanding News Desert, and former executive with The Wall Street Journal and The New York Times, thinks even more perspective is required. To understand the void TV is being asked to fill, you first have to assess the full scope of what’s been lost.

“In terms of newspapers, there have been two losses,” she explained, in a telephone interview. The first was the shuttering of more than 1,700 newspapers in recent years. The second was the loss of coverage that occured when, to counter plunging revenue and chaotic variable costs, big metro newspapers ended rural home delivery. “These papers bound regions together,” Abernathy says. “They showed us how we might be vitally related to people five or six counties over. You might have the same problem or face the same opportunities, whether you’re dealing with opioid crisis, health care, or the like.”

To understand why the future of television and the current plight of newspapers is linked, Abernathy refers to the 2012 FCC report, which listed eight critical information needs: emergencies and public safety, health, education, transportation, environment, economic development, civic life, and political life. “The key reason the newspaper industry is the subject of so much attention and concern is that research indicates that newspapers continue to provide a substantial portion of the original reporting — the original production of news — that then circulates throughout the rest of the local media ecosystem,” the report noted. TV, by contrast, devotes “inadequate air time to serving the critical information needs of local communities.” To that end, Abernathy fears what’s been lost is too much for TV newsrooms to pick up, even if they were incentivized to try.

“The collapse of the news ecosystem creates an undue burden by assuming television is going to take over that,” Abernathy says. “It’s unrealistic for us to expect they can do that.”

As of 2017, TV newsrooms employed more journalists nationally than newspapers, according to an industry survey. It’s a positive-sounding statistic, but misleading in terms of potential for expanded coverage. For starters, the difference isn’t large: 27,100 to 25,000. For context: Ten years ago newspapers fielded more reporters than current levels of TV and newspaper journalists combined. Also, a community typically has more news stations than daily papers, creating redundancy in beat coverage, since all stations will cover many of the same big stories and regional narratives. So, having more TV journalists on the job doesn’t translate into broader or more in-depth community coverage.

Forget every other explanation you’ve ever heard: There’s one reason why mayhem always seems to lead and dominate nightly news broadcasts. The basic “Jill shot John” crime story is reliably popular content that seldom requires follow up and costs virtually nothing to produce, relative to the time and resources required to do investigative or enterprise reporting. That kind of work may require hours of interviewing, weeks of source cultivation, and months or years of institutional knowledge and beat coverage. It’s not that watchdogging government and industry isn’t important. It just takes more time and resources to produce and move that kind of information, and advertisers may have no interest in supporting it.

“My students are always surprised that a Pulitzer Prize can be bad for business,” Abernathy says. “Advertisers and city fathers are really mad at you for having exposed what they didn’t want exposed.”

A Knight report titled “Local TV News and the New Media Landscape” encouraged TV news crews to “drop the obsession with crime, carnage, and mayhem.” It encouraged stations to focus on “ways to connect with local communities through issues similar to those proposed by the FCC: education, economy, transportation, etc.”

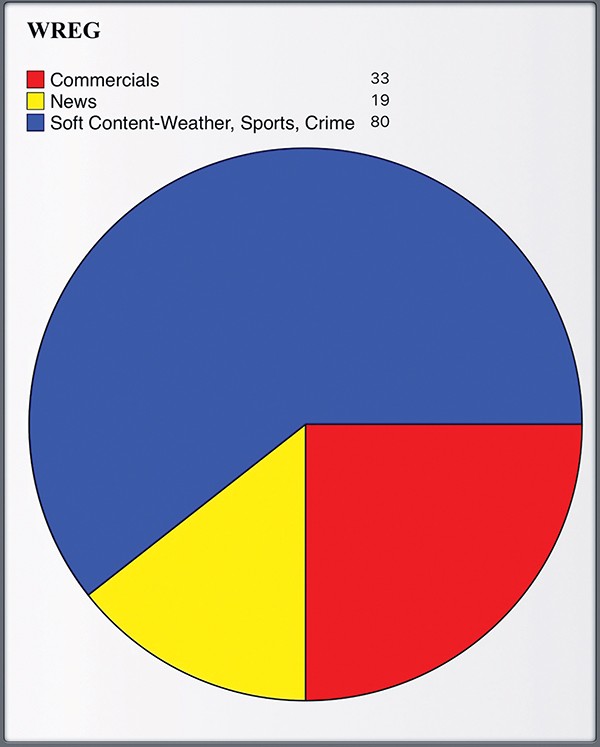

Studies have shown that most local news is comprised of “soft content” — crime, weather, and sports. In some instances, according to the UNC report, such content can comprise 90 percent of a station’s news broadcast. A four-day sample of WREG Channel 3’s 10 p.m. broadcast, taken from Tuesday, May 14th, to Friday, May 17th, found 80 percent of alloted news time devoted to crime, weather, sports, and other soft content, including lotto numbers and station-branded money giveaways. Twenty percent of the station’s reporting was devoted to violent or disruptive crime and punishment, and that number would go up considerably if you folded in more heavily reported crime and police-related features covering topics like sex trafficking and a state execution by lethal injection.

Most of WREG’s news was local, but out-of-market content was always present and included reports about wildfires, a helicopter crash, a kitten found in a trash can covered in spray foam, and a horse stuck in the mud.

As a frequent ratings winner in the Memphis market — “on top morning, noon, evening, night,” according to their own reports — WREG is exemplary of what virtually all local TV news looks like today.

Although television news would seem to be in an enviable position as the dominant source for local information, and consistently posting double-digit profits, changing user habits may be taking a toll on viewership. According to Pew research, the slow erosion of TV news users kicked into overdrive in 2018, particularly among viewers under 50.

Pew’s findings show just 50 percent of U.S. adults obtained news regularly from television in 2017. That marked a 57 percent decline from the previous year. “Local TV has experienced the greatest decline, but still garners the largest audience,” Pew’s associate director of journalism Katerina Eva Matsa wrote. Being the largest combines with regular election year capital injections to keep TV growing in terms of value, even as the audience appears to be falling away.

“It’s very hard, when you’re still successful, to imagine a new way of doing things, or take the risk of destroying your current business model,” Abernathy says. “There’s what’s called a waterfall effect,” she says. “Things go down incrementally at first, and then all of a sudden it just drops, as it did with newspapers.”

At just about the time Gray was sealing the Raycom deal, a trio of Memphis journalists sat down for a sprawling interview on 88.5 FM, Shelby County Schools Listen Live. It was a rare and insightful look at the role of clickbait — what you get when public interest determines the public interest — in local news production.

“You have to sit there and look at a big board to see what’s trending across the company,” Nicole Harris, a digital producer with experience in newspapers and television said. “So, if something’s doing well in another market or trending on Google, we need to get that on our site, too, to get people to click on it, because we’ll get those hits.”

Harris was joined by Memphis media critic Richard Thompson, who tweets under the handle Mediaverse, and Memphis Association of Black Journalists president Montee Lopez, a senior producer for Local Memphis.

“It’s not fun, especially when you’re being asked to post something you know is dumb,” Harris continued. “There are times when I would push back. I would say, ‘We don’t need to do this.’ But, at the same time, you only get so many get-out-of-jail-free cards.”

The SCS interview was organized in response to social media posts made by area stations that don’t make it clear when shocking crime- and disaster-related content isn’t local. “People don’t read past the headline,” Lopez said. “That’s what a lot of our social media producers count on. They know they’re going to see that headline — ‘Man Kills Wife in Bizarre Way.’ It’s hundreds of miles away, or thousands, but they know because of the headlines it’s going to get the clicks.”

Harris, and Lopez aren’t the only area TV journalists who’ve shown some self-awareness. Nightly crime reporting was compared to clickbait in an interview Richard Ransom gave to Memphis magazine, when the news anchor and reporter transitioned from his former gig at WREG to his current home at Local Memphis. “Crime-all-the-time coverage is lazy,” Ransom was quoted as saying. “It’s low-hanging fruit. It also doesn’t reflect in a balanced way the city I know. It glorifies violence and can fuel racial stereotypes.”

Back to the original questions: Why are all of Memphis’ TV news stations about to be under new ownership, and why does it matter? Unlike the newspaper business, where industry titans are frequently bought and sold in the wake of catastrophic revenue declines and sudden value loss, change in the TV industry is motivated by its history of success and potential for future earnings, buoyed by enormous political campaign spending every two years. Memphis’ station-ownership turnover reflects an industry where the biggest companies are all looking to get as big as regulations allow, and to challenge those boundaries to take advantage of scale for profits.

In some ways mass consolidation in media makes sense. Big jobs require big organizations, and producing daily news content across a range of interests is an enormous and expensive job. The problem is, the bigger and farther away the ownership groups get, the smaller local newsrooms and their range of reporting become.

So, you probably won’t notice when everything changes and new owners take over all the local television stations — but maybe you should.

Clarification: Numbers in the WREG chart represent minutes, not percentages. So 132-minutes = 100 percent. Commercial time is subtracted from the whole before determining the percentage of hard/soft news content. Sorry for any confusion this may have created.