JB

JB

Before Wednesday night’s debate l to r): Mayor A C Wharton, Mike Williams, Harold Collins, Jim Strickland

JB

JB

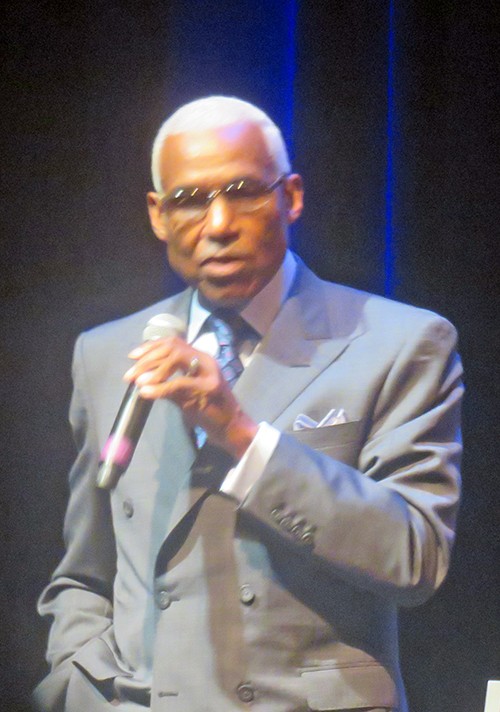

Debate moderator Kyle Veazey

Memphis is not about to rival Nashville in the number of mayoral debates, forums, and other ensemble events — 40-odd and counting — held in the state’s capital city this year, but we’re getting there. Several such events have been held by now in our town’s mayoral race, and they seem to be drawing lose attention.

One more is in the can after Wednesday night, a debate co-sponsored by The Commercial Appeal and the University of Memphis at the University’s Rose theatre, and another one is scheduled on Thursday night at Central High School under the auspices of the Evergreen Historic Association.

And people, even in these dog days of summer, seem to be paying attention.

So who’s winning?

One way of answering that is to fall back on the tried and true all-have-won-and-all-must-have-prizes approach. That’s usually an evasion, but so far this year it seems to describe what’s happening in these mayoral-candidate get-togethers.

By common consent, it would seem, the field has settled on four candidates regarded as “viable” — incumbent Mayor A C Wharton, City Councilman Jim Strickland and Harold Collins, and Memphis Police Association Mike Williams.

Former School Board member Sharon Webb was involved in a couple of the early ones, including a widely watched one televised last week on WMC-TV, Action News 5. But there is general agreement that her performance in those encounters was not up to the standard of the others, and she is unlikely to figure in many more debates as such.

As for the other four? Well, yes, they all have “won,” in the sense of staking a legitimate claim to leadership in the city.

THE CASE FOR MIKE WILLIAMS:

Gotta have one winner? Okay, it’s Mike Williams, who, ironically, is not considered to have much of a chance to actually win the Mayor’s race and was not included in one or two early get-togethers. Williams’ fund-raising is miniscule compared to the other three and his support network, while enthusiastic, is — how to say it? — compact.

Moreover, he was long regarded as being a one-trick pony, in the race solely to dramatize the case for restoring lost benefits to city employees — especially first responders and even more especially the dwindling ranks of the city’s police force.

But Williams proved himself a strong, articulate performer in last week’s debate and on the stage of the Rose Theater Wednesday night. And he did so without forsaking his main cause or artificially broadening it but by relating the case for public employees to the core issues of public safety and the economic health of the community and by relating it, too, to other grass-roots concerns, like the ongoing movement to save the Coliseum.

Regarding this or that intractable crisis or malaise that afflicts the city, Williams points out that Mayor Wharton has been in office for six years, and Strickland and Collins for eight years and have been unable to deal with the problem. He suggests with an air of reasonability that maybe he could.

In two short weeks, Williams has transcended a lot of people’s low expectations for his candidacy and demonstrated that he belongs on the debate stage. That’s a win.

THE CASE FOR HAROLD COLLINS:

Similarly, Councilman Collins has been able to enunciate a vision for the city by extrapolating from his achievements within his own Whitehaven-based district — including a massive ongoing redevelopment project on Elvis Presley Boulevard, which, as he demonstrated Wednesday night, began from the level of repairing sewers on up to some wholesale renovation.

Collins has also looked into the nether parts of some of the bright and shiny projects now on display as civic successes for the current regime and seen and described some overlooked tarnish — like the $9 -and $10-an-hour jobs and the filling of positions with temps at Electrolux instead of the high-paying positions the public had been led to expect.

Decrying conditions that lead the city’s youth to seek post-graduate employment elsewhere, Collins, something of an Horatio Alger up-from-nothing case himself, is an apostle for “engineering, finance, and technology” jobs. He has eloquently called the Wharton administration to account for what he calls breaches of faith with city employees and for other alleged inconsistencies affecting the public at large.

nd, like his Council colleague Strickland, Collins emphasizes public safety, calling for swift and punitive reaction to outbreaks of violence.

All in all, the gentleman from Whitehaven has made a good case that his record on the Council merits a promotion.

THE CASE FOR JIM STRICKLAND:

At times, the District 5 Councilman and budget maven, whose district encompasses Midtown, power sectors of the Poplar Corridor, and relatively humble middle- and working-class residents as well, seems to get snagged on rote repetitions of his bullet-point issues, which can be summed up by the words Safety, Blight, and Accountability.

But Strickland can expand on these basic positions (which, let it be said, are all perfectly sound present-tense concerns) with some interesting improvisations — like his call for a “residential pilot program” of tax abatements for urban residents who would improve their homesteads and his sponsorship of a grant program for those who recover tax-dead properties.

As impediments to crime, Strickland couples his emphasis on stepped-up “Blue Crush” police activity with proposals for reviving community centers and using Boys’ and Girls’ Clubs as outreach to troubled youth. A mite idealistic-sounding, perhaps, but worth a try.

Strickland should be thankful to Mayor Wharton, who, mindful of the general sense that he is the Mayor’s chief rival, has launched head-on attacks on him in the last two debates. These have allowed Strickland to respond in ways that demonstrate he is something other than the “generic white man” that one wag has called him and can Do the Dozens with the best of them.

A rock star might have envied the audience squeals Strickland got from his animated thrust at Wharton during a back-and-forth Wednesday night on civic economy. “He increased the debt to 47 million dollars, He did it! Do not believe the slick maneuvers and the corny stories!”

In sum, a worthy challenger.

THE CASE FOR A C WHARTON:

Perhaps the most admirable thing about the current Mayor, who knows from polls and other sources that he’s got a real race on his hands, is that he is unabashed about putting forth policy rationales that may have questionable payoff value with the electorate at large but seem to him worth stating.

One case in point is his running against the tide on the issue of public safety. Wharton defends his record on the issue, contending that, high-profile incidents to the contrary notwithstanding, the rate of violent crime is down. But, even conceding there is a problem, the Mayor insists that “locking ‘em up” is not the solution. As he said Wednesday night, he’s for “keeping the children out” rather than “taking more and more of them in.”

And, to calls from opponents Collins and Strickland to strengthen the hand of Juvenile Court, Wharton assumes an air of injured patience and suggests they are not aware of Department of Justice mandates that would decree otherwise.

Similarly, the Mayor’s attitude toward the city’s straitened budget is that, as he repeated Wednesday night, “we can’t cut our way out of this, nor tax our way out.” He maintains that “growth, growth, growth” is the only solution and touts his success in bringing in money from outside granting sources and his administration’s zealous recruitment of new industry via PILOTs (payment-in-lieu-of-taxes) and other inducements.

The policy, scoffed at by some of his opponents, of catering to the needs of “millennials” via bike lanes and other innovations is justifiable because it will attract young trained professionals to the city, says Wharton, who insists that statistics show the policy is working.

Wharton can be brazenly realistic in defending his administration’s cuts in employee benefits (“There are substitutes for health care, but there’s no substitute for the pension plan”), and he responds to charges from Collins and Strickland regarding everything from the slow restoration of money owed the school system to the winnowing down of police ranks to the holding back of tax levies already authorized by turning the argument around and blaming the Council.

At bottom, the Mayor’s case for reelection is that he’s succeeding more than people realize on jobs and other issues and certainly more that his critics acknowledge.

Beyond the cases made in public exchanges and elsewhere by the various contenders for the office of Mayor (and expect further details here and in subsequent articles), there are demographic and pre-existing political facts of life that will go toward determining an ultimate winner. But be assured: This race is truly competitive, and all members of the current Front Four are credible candidates. Stay tuned.

Meanwhile, to get a sense of some of the sass and vinegar of the Wednesday night debate, look at these two video examples. In the first, Mayor Wharton takes off rhetorically against opponent Jim Strickland. In the second, Councilman Collins returns the favor to the Mayor: (Mike Williams bides his rime as a spectator in both frames.)

Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker