Even though they won’t start until August 8th, the Beijing Summer Olympics already have generated controversy around the world. Human rights activists are urging a boycott of the games, turning what is usually an over-hyped athletic competition into over-hyped political football. (Sadly, football isn’t an Olympic sport, because, hey, we’d kick butt.) But I digress.

We here at the Memphis Flyer know that most of you will not be heading to China, no matter your political leanings on the subject. With that in mind, we’ve compiled some local versions of Olympic events for your amusement and edification. Because that’s how we roll. — Bruce VanWyngarden

The Parallel Bars

The competition is stiff along one block of Madison Avenue.

by Michael Finger

Arm muscles rippling, backs straight as arrows, legs braced securely, eyes straight ahead, concentration focused. It’s poetry in motion, and the awed spectators wonder just how long the participants can continue until they slip and tumble to the ground.

Oh sure, the parallel bars competition at the Olympic events is fairly interesting, but what’s that got to do with this? Here, we’re talking about the drinkers perched on the stools, lifting frosty mugs of Budweiser to their lips at a pair of “parallel bars” in Memphis: two Midtown landmarks named Old Zinnie’s and Zinnie’s East.

From the outside, Old Zinnie’s is a curiosity — a turreted building constructed in 1905 at the corner of Madison and Belvedere that over the years has housed a drugstore, a beauty parlor, and even a bicycle shop.

“We opened Zinnie’s in 1973 or 1974, right after Huey’s opened,” says Perry Hall, current owner of Zinnie’s East. “The original owner was a guy named Gerry Wynns. Everyone called him Winnie, but he didn’t like that name for a bar, so they named it Zinnie’s.”

Precisely 109 meters to the east (a distance sanctioned by the Olympics committee), Zinnie’s East is a newer establishment, a two-story brick structure erected on the site of a white cottage that was home to a classical-music bar fondly remembered as Fantasia.

So why build two Zinnie’s practically side by side?

“We thought we were going to lose our lease down at Old Zinnie’s, because the landlord kept raising the rent,” Hall says. “So we tore Fantasia down in 1984, and our plan was to just let the other place go and build a new one right here.”

And?

“We opened Zinnie’s East on February 14, 1985 — Valentine’s Day. And on the 13th we walked away from the old place thinking it would go downhill,” Hall says. “But it wouldn’t die! It just would not die. And now it’s become a haven for all the kids from Rhodes.”

Old Zinnie’s is now owned by Bill Baker. “Not the Bill Baker from Le Chardonnay,” Hall explains, “but the other one.”

Having two bars with essentially the same name, he admits, has confused customers.

“Old Zinnie’s is associated with just a beer and a hamburger, and for a long time people didn’t think we [at Zinnie’s East] did anything but serve beer and hamburgers.” Instead, the new Zinnie’s offers a wide-ranging menu, tasty plate lunches, and for those who care nothing at all about their cholesterol levels, a concoction called the Zinnie-Loney: fried bologna, Swiss cheese, and grilled bacon on a bun. Angioplasty costs extra.

Old Zinnie’s has some nice architectural touches inside, including a magnificent old bar with tile accents and illuminated stained-glass panels spelling out “Zinnie’s.” But “new” Zinnie’s (as it’s often called) features an underappreciated work of art — etched glass panels, designed by Memphis artist (and frequent Flyer contributor) Jeanne Seagle that, says Hall, “has the whole panorama of what Madison Avenue was like when we opened in 1985 — all the characters, from Monk to Dancin’ Jimmy.”

And there’s more. Upstairs at Zinnie’s East is yet another bar, called the Full Moon Club. It originally opened across Belvedere from Old Zinnie’s, then moved to the second floor of Zinnie’s East, taking over space that had been used for catering private parties.

Unfortunately, the Olympic judges refuse to acknowledge that the Full Moon Club and Zinnie’s East would qualify for the uneven parallel bars competition — it’s some silly technicality — but as far as parallel bars go, Old Zinnie’s and New Zinnie’s are both winners.

Synchronized Swimming

At the MJCC, water lovers find a multitude of choices.

By Mary Cashiola

In one corner of the pool area, boisterous pre-teens are giggling and riding clear rafts around a little “river.” Nearby, adults swim laps in roped-off lanes, kids fly down two-story waterslides, and teenagers dive off the springboard into a 12-foot-deep diving well.

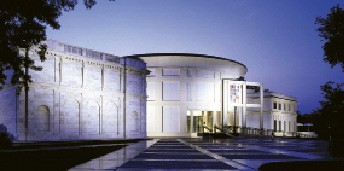

Nestled among trees, condos, and office buildings, just a few hundred yards off Poplar on the Germantown/Memphis border, the Memphis Jewish Community Center pool is what you might call a water wonderland.

Originally built 40 years ago, the pool at the community center reopened last summer after undergoing several million dollars of renovations.

“The Jewish Community Center used to be downtown. When it moved here, the pool was built before anything else,” says aquatics director Danny Fadgen. “It’s on the same footprint, but we’ve added things like beach entries and the lazy river.”

They’ve added so much, in fact, that it seems more like a family water park than your garden-variety pool.

The lazy river is 286 yards around, with a five-mph current and sprinklers that shower users from above.

(Of course, it’s not lazy all the time. Sometimes the swim team practices in it by swimming upstream. Seniors exercise there, too, by walking upstream.)

Fadgen, who has worked at the center for 11 years, now sees three and four generations of families together at the pool.

“We never used to have that. We put in lots of ‘funbrellas’ and canopies that have created a lot of shade,” he says. “In years past, we didn’t have much shade, and it was too hot out there.”

But while shade is a compelling argument, it can also be said that there is a little something for everyone.

For the thrill seekers, 12,000 gallons of water gush through the red and blue waterslides — one completely enclosed — each minute.

For younger kids, there is what Fadgen calls the splashground — with a smaller slide, water cannons, and rope ladders — in about a foot of water. For toddlers, there’s a play area with sprinklers, a cushioned floor, and no standing water.

“When the pool was first built years ago, the place was packed wall to wall. You couldn’t find a chair,” Fadgen says. “A few years ago, with all the pools in town and in people’s backyards, our usage was going down dramatically, no matter what we did program-wise.”

They decided to invest in an upgrade, and the turnaround has been just as dramatic. On opening day last summer, about 2,000 people came through the gates. Even now, Fadgen says people call every day and ask if they have summer-only memberships. (They don’t.)

On weekdays, the aquatic center is used for swim lessons in the mornings and open to members from noon to 9:45 p.m.

Fadgen employs about 60 lifeguards on staff and has nine guards on duty for each shift.

In the past, he says, most of the assists — when lifeguards have to get involved — would happen when inexperienced swimmers first got more confident and left the shallower waters. Now, however, more than half of the pool area is only three feet deep.

“With all the attractions, people thought it was going to be more dangerous,” Fadgen says. “It has required more lifeguards, but it’s actually safer. We don’t have as much deep water as we used to have.

“Everybody’s just smiling from ear to ear,” he says. “Somebody with a backyard pool was telling me yesterday, ‘Everybody used to come to our place, and now we hardly see them.’ They all come here instead.”

The Snatch

and the Clean and Jerk

Even weightlifters need a little grooming.

By Bianca Phillips

Competitors in an Olympic weightlifting match vie for the quickest “snatch” and a flawless “clean and jerk.” But for those uninitiated in the sport, these terms could bring to mind other things, like bikini (“snatch”) and body waxing. (Get it? Clean, jerk.)

If you plan on being seen in a bathing suit this summer, you’ll need a little snatch waxing and clean jerking. (Hey, even weightlifters keep themselves well-groomed.)

According to esthetician Amy Gregory, the most popular waxing service at Midtown’s Hi Gorgeous salon is the Brazilian wax, which removes all the hair from the front and back of the, um, private areas. Ladies can keep a “landing strip” if desired.

If the very thought makes your hoo-ha hurt, Gregory also offers a half-Brazilian, which “leaves hair on the lady bits.” Other waxing services include underarms, legs, arms, back, chest, and various facial areas.

Gregory uses a hard wax that resembles a blob of honey and feels tacky to the touch. The warm wax is applied to the skin, and Gregory waits about one minute for the wax to cool before ripping it off in one quick jerk. Though most body parts can be waxed rather quickly, full-body waxing can take about three-and-a-half hours.

“The 40-Year-Old Virgin has ruined so many people’s perception of waxing. People come in thinking it will be the most painful experience of their lives,” Gregory says. “It’s really not that bad. Please don’t watch that before you come in.”

Gregory says waxing is superior to shaving because it eliminates itchy stubble and razor burn, decreases in-grown hairs, and waxed body parts stay smooth for weeks.

Not an exhibitionist? No problem. Gregory performs her services, which also include facial and spa treatments, in a small private room near the back of the salon.

“I play cool relaxing music to make people feel comfortable,” Gregory says. “I’ve been playing a lot of Bjork lately. Today, it’s mostly been Bob Dylan covers.”

A few things to consider before you make a waxing appointment: 1) Hair must be 1/8 of an inch to 1/4 of an inch long before it can be waxed, 2) it’s a good idea to take ibuprofen first but stay away from aspirin as it thins the blood, 3) if you have long back hair, it should be trimmed before the appointment, and 4) take a shower beforehand.

“Please don’t come straight from the gym and make me wax you,” Gregory says. “Have some decency.”

Individual

Medley

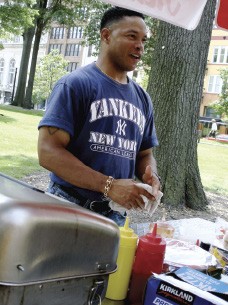

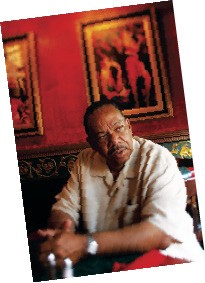

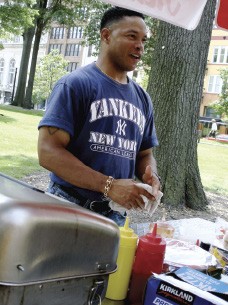

Thomas Nolan fights fires, makes art, and grills great hot dogs.

by Chris Davis

A concerned-sounding customer leans on Thomas Nolan’s Court Square hot-dog cart, mopping the sweat from her melting face with a tissue. “I don’t know how you stand it,” she says, handing Nolan a moist wad of cash and greedily snatching from his hand a perfectly grilled six-inch dog with sauerkraut. “It’s so hot out here,” she adds, fanning herself with her dog-free hand.

“Oh, I don’t think it’s too bad,” Nolan replies affably. “Well, at least as long as the sun stays behind that cloud.”

Soon after the woman walks away Nolan expresses his true feelings on the weather.

“Sometimes I just want to tell people that it’s not really all that hot, and they don’t even want to know what hot is,” he says authoritatively, wiping down the surfaces of his shiny chrome cart until the sun’s reflection is almost blinding. When not hawking his hot dogs downtown or making abstract paintings at his fine-art gallery on South Main, Nolan works as a firefighter, so when he talks about heat, he knows what he’s talking about.

“I was on that one,” he says, nodding in the general direction of the gutted husk of the First United Methodist Church, which burned in October 2006.

“People don’t want to know what hot is,” he says, recalling the terrifying moment when the church’s steeple collapsed.

“I want one of your Memphis dogs,” says a regular customer, rushing by the cart without stopping. “I’ll be back to pick it up in a few minutes,” he calls behind him.

“He’s a believer,” Nolan says of the hurried man. “He bought a dog on the very first day I was out here, and now he comes by to get something at least every other day.”

Nolan didn’t have hot dogs in mind when he graduated from Southside High School in 1982. He had a baseball scholarship to LeMoyne-Owen College and dreamed of playing in the big leagues. Or of at least working as a professional artist. Or maybe both.

“I worked in a lot of restaurants,” Nolan says of his college days. “And I’m going to be cocky about it. I got really good at cooking. And if you’ve got something inside of you, you’ve got to let it out.

Nolan’s downtown hot-dog cart is part of his latest attempt to be all that he can be. He describes the high-intensity training he does for the fire department as filling the void that baseball once occupied in his life, and he calls dressing dogs an extension of his abstract painting.

“It’s all about the color,” he says. He begins building a Chicago-style dog by pulling a grilled all-beef kosher frank out of the fire and laying it gently on a bed of sweet neon-green relish. “There’s the green and the yellow,” he says, adding a squirt of mustard and a handful of whole pickled chilis. “And, of course, the red,” he continues, piling on thin slices of fresh tomato.

“It’s like I’m trying to bring a little bit of New York or Chicago to Memphis,” Nolan says. “I’ve got my cart and my park and my jazz,” he says, patting his radio.

“Man, what is that playing on your radio? Coltrane?” a man asks, walking up to the cart and ordering a Polish sausage.

“I don’t know,” Nolan answers. “It’s on satellite.”

“Well, I don’t know either, but it’s hot,” the man says, picking up a menu. The dog-man grins.

“Yeah, it’s hot,” he agrees, dropping a sausage down on the grill.

Thomas Nolan’s hot-dog cart can be found on Court Square for lunch most weekdays throughout the summer. He parks his stand outside of Raiford’s Hollywood Disco in the evening on weekends.

The

Memphis Marathon

The drive to impress visitors

can be daunting.

by Preston

Lauterbach

When the Persians invaded Greece in the fifth century B.C.E., a Greek soldier ran like hell from Marathon, the port on the Aegean Sea where the Persians landed, to inform Athenians of the victory of the Greeks over the Persians. The distance of the epic jog? Twenty-six miles. A legend and a test of athletic endurance were born.

This summer, a different invader will target the citizens of the Bluff City. They are a little girl cousin from suburban San Diego, a college roommate and her husband on their way from Austin to Atlanta, our friends and loved ones, descending on Memphis from all sorts of locales. Our task, once they land, is no less daunting than what befell that marathon runner: We must make a Memphis marathon.

We love the city’s grand trees and architectural splendor. And we’d prefer that summer visitors from out of town see only the same. This, like any summer Olympic event, requires great preparation and the will to negotiate obstacles, some unforeseeable, some so daunting as to appear impossible to overcome. If you can drive your visitor at the speed limit for 26 minutes without laying eyes on urban blight, you win. But while victory is sweet, participation is what counts.

Don’t worry. We’ll get the benefit of the doubt whether they’re driving or flying in, since airports in plenty of other cities are dumped at the fringe of town, and properties adjacent to freeway off-ramps tend to not be the most desirable wherever you go. The properly selected driving route represents the key to managing their impressions from there. Look, it’s not easy, but do you think that Greek runner sprawled out beneath a fig tree between Marathon and Athens, waiting for his manservant to feed him one of those plump bunches of grapes that seemed to grow throughout the ancient world? Hell no.

I’ve found that a Midtown departure point, while challenging, offers plenty of benefits. A little zig-zagging through Central Gardens can kill a good 10 minutes if properly milked. Then I head east across Cooper, maybe to Cox Street, or perhaps to East Parkway, meandering beneath grand oaks and betwixt charming old homes. Overton Park can be your friend, or it can utterly blow it for you. You’ll have to weigh that risk, taking into consideration the day and time of your roundabout. From there, lovely Evergreen welcomes you and holds hands with your party as you all skip gaily toward Belvedere.

Still, we must be at the ready with explanations for the unpredictable sights that can complicate a tour of city beautiful. (“He’s not a bum, he’s a … performance artist.”) Don’t ever count yourself out, though.

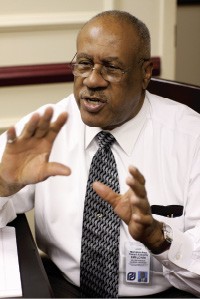

The

Triple Jump

A trip to Beijing takes

preparation and perseverance.

by John Branston

Day-dreaming of a trip to the 2008 Olympics in Beijing in August? You’ll need a solid-gold bank account, the endurance of a marathon runner, and the agility of a gymnast. A coach-class airline ticket on Northwest Airlines starts at around $1,700, and the trip takes 23 to 40 hours. You’ll rack up more than 16,000 miles round-trip.

Memphis’ Loujia Mao Daniel is something of an authority on distance travel. She was born in Beijing in 1972, came to Memphis in 1996, and has made five trips back home to visit her parents, who come to Memphis in alternate years. Plus, she’s a flight attendant for Northwest who’s apt to be called on short notice to pack up for an international flight.

Growing up in a tiny apartment in China when Chairman Mao was still alive, Daniel remembers writing stories in elementary school about what China would be like in the year 2000. She never imagined that Beijing would host the 2008 Olympics or that she would come to the University of Memphis to study economics.

Unless you’re University of Memphis basketball ambassador John Calipari or a pilot for FedEx, traveling to China is still pretty exotic. For starters, you need a visa from the Chinese embassy in Washington, D.C., or Houston, and you must either apply in person or get a travel agent or friend to take your passport to the embassy in person. The visa fee is $130 per person. Daniel says the quickest way is to do it yourself and to get to the office before 10 a.m.

From Memphis, you fly to a gateway city such as Detroit, Minneapolis, or San Francisco, then on to Tokyo, and from there to Beijing or Shanghai. Going over, you’ll arrive on the second day. Coming back, it will be the same day when you get home, or what Daniel calls “the longest day.”

To combat jet lag, she strongly recommends using mileage awards to upgrade to business class, with reclining seats and good food and less chance of being seated near restless small children. But she still allows herself a 24-hour recovery period after exceptionally long trips.

Olympic venues are scattered all around Beijing, which is “very congested, like Tokyo.” Daniel recommends booking a four-star hotel, which can be obtained for about $100 a night.

“It’s a cash society,” she says. “You’ve got to bring cash, because 90 to 95 percent of businesses don’t take credit cards.”

She suggests hiring a Chinese university student who speaks English as a personal tour guide, because Beijing is huge and public transportation is “always packed.” Don’t go to small restaurants or drink tap water, to avoid getting sick.

And make sure you have Olympics tickets lined up. They are hard to get, even for the Chinese, who have to go through a pre-sale process before they even have a chance to bid for limited tickets to prime events. “It might be easier to buy them in the United States,” Daniel says.

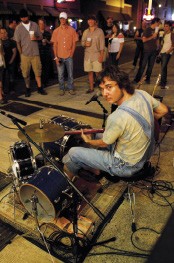

Rings

Deep-fried competition

at its best.

by Greg Akers

Over in Beijing this summer, a bunch of fit folks are going to dazzle an international audience with feats of muscular grace. One such event you’ll be subjected to is the gymnastics “rings” competition, where athletes grasp a pair of circles suspended in the air and commence to swing themselves up, down, and around — with the occasional awe-inspiring mid-flight holding pattern thrown in, where they make their bodies into a cross and stay in position for a few agonizing seconds.

Screw those guys.

In Memphis, “rings” means one thing: onion rings. It’s deep-fried athletics at its best. Nobody, not even Wikipedia, knows who invented onion rings. But it takes a city like Memphis to make the eating of them worthy of Olympics competition.

Unlike with the International Olympic Committee, in Memphis rings, there’s no governing body and no standardized set of rules and regulations. Everybody offers their own twist on the spherical sport, with variations coming from size and type of onion used and batter and seasoning distinctions.

Rings athletes must always exercise judgment when choosing their venue. Among the best rings in the region are those found at Belmont Grill, Bigfoot Lodge, Huey’s, and Velvet Cream — and they’re all different from each other.

The rings at Belmont Grill taste like Zeus handed them down from Mount Olympus. Eating them requires an uncanny mind that can overcome circular logic and a well-developed hand-eye coordination that will help you stick the landing.

Bigfoot Lodge’s rings have a touch of local flavor: They’re served with a side of barbecue sauce. Acrobatic dipping will score you extra artistic points from jealous sidewalk judges.

If you think bigger is better, Huey’s is your game. Theirs are rich brown behemoths that put the “Oh!” in onion rings. And if you order the Grand Daddy Huey Burger, you’re going to get served — two hamburger patties topped with a ring.

The world traveler should hot-foot on down to Hernando, Mississippi, to Velvet Cream — called “The Dip” by seasoned veterans — and flex your muscles with their rings. Make it a biathlon and enjoy one of their famous shakes, freezes, or slushes.

Though the Olympic rings event is for males only, in Memphis, the competition is gender neutral. It doesn’t matter if you’re representing Team XX or XY. Anybody can give rings a sporting chance.

Many rings competitors are actually two-sport athletes. At Corky’s BBQ, you can get the “Onion Loaf” — a tower of onion rings — which merges a pair of Olympic events: rings and the pole vault. It’s strictly for the serious competitors who don’t consider rings a mere game.

Never forget, though, that rings is no spectator sport. It’s all about your teammates: Though there’s an “I” in rings, that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t share!

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks  by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks  by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks  by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks  by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks  by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks  by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks