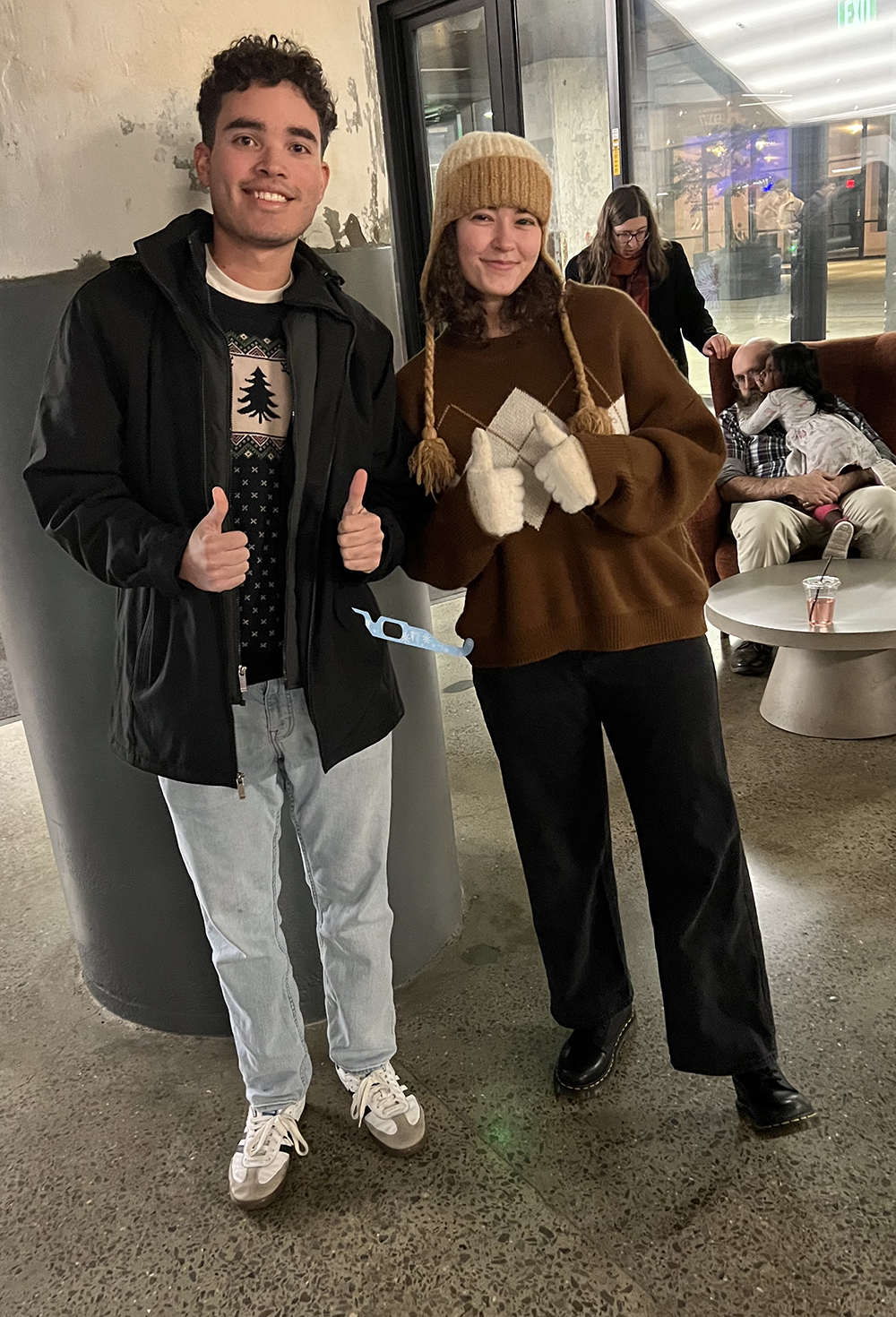

When Steve Hirsh and Friends take the stage at the Green Room at Crosstown Arts, they will have something in common with the audience. You won’t know what songs they’re going to play, and they won’t know either!

Hirsh will make the long drive from his home in Bemidji, Minnesota, to play with a group of Memphis’ finest “free” musicians, all of whom have embraced extemporaneous music-making for years.

Saxophonist Arthur Edmaiston says both he and saxophonist/flutist Chad Fowler were steeped in improv in the 1990s, with regular sessions at Young Avenue Deli that coalesced around saxophonist Frank Lowe. “He came back to Memphis in the ’90s after a 20-plus year career,” Edmaiston says. “It was a weekly gig, and that was a great way for us to all develop our own thing and develop as a band and improve as musicians. And we recorded those shows. See, we all lived in the neighborhood, so we’d go and we’d do the gig and record it, and then we’d come back home and drink on the porch, whoever’s porch, and listen to what we had done earlier and tear it apart and kind of learn from it.”

“Is this free jazz?” I ask Hirsh, referring to a genre tag that was often applied to Lowe.

“I’m going to ask you not use that term,” Hirsh replies.

As bassist Khari Wynn explains, many improvisational musicians consider the term a trap. “As soon as you drop the ‘J’ word, you get two avenues of thought. People are immediately like, ‘Oh, I don’t like that. It doesn’t have words. It’s too out there.’ Or you get the other side of it where people are like, ‘Oh yeah! I’m definitely a jazz fan!’ So then they expect to hear some of these certain figures repeated or played, and then if you don’t do that, then you’re not authentic.”

Hirsh was originally from New York City, the crucible of modern jazz, but left when he was still a teenager. “I wasn’t even aware of all that stuff,” he says. “I grew up on rock-and-roll. I didn’t start learning about jazz until I was in high school. I just kind of stumbled across some records. I went to the ‘University of Liner Notes,’” he says. “I moved out to the Bay Area, and I was playing in rock-and-roll bands and blues bands and really got into the [Grateful] Dead, which is really where I learned about improvising.”

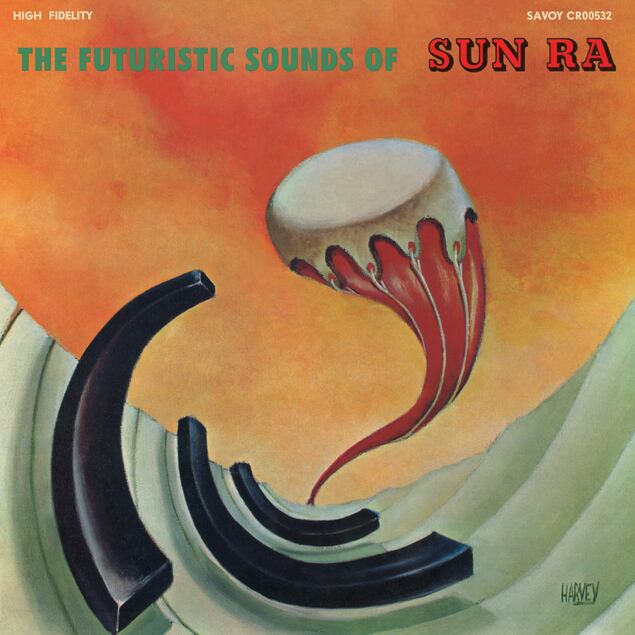

Meanwhile, the group that became Deepstaria Enigmatica originally brought three of these players —Fowler, Wynn, and Alex Greene — together with David Collins and Jon Harrison in 2022, opening for Jack Wright’s improv trio Wrest. Something clicked. “That October, we went into Sam Phillips Recording and improvised for several hours,” says keyboardist Greene, who is the music editor for the Memphis Flyer. “A tiny fraction of that became our first album, but that day was explosive. It was like the big bang for our group.”

The Eternal Now Is the Heart of a New Tomorrow consists of two tracks, both more than 20 minutes in length. Unlike the stereotypical free jazz freak-outs of the ’70s, Deepstaria takes a whirlwind tour through 60 years of instrumental innovation. Soulful grooves dissipate into ambient atmospherics and sheer sonic textures.

That album, released on the celebrated ESP-Disk label, which also released Lowe’s 1973 debut, is getting some attention, as with DownBeat’s recent positive review of the disk.

Edmaiston, for his part, has also been a maverick of improvised music here, either with SpiralPhonics or with trailblazer Ra-Kalam Bob Moses, not to mention ad hoc groups and his early years with Lowe.

These Memphians’ slippery eclecticism is what attracted Hirsh to them. “There’s no genre about it. It’s a process. It’s a way to make music,” he says. “Our brains differentiate between noise and music, but we learn what music is. There are people who intentionally work with that boundary, and I think that’s perfectly valid. But I always want a narrative. I want a story arc in the music I play. Playing with these guys is hip because they all want the same thing, and we’re all kind of reaching for the same thing when we’re playing — at least when we’re playing together.”

“We just go in any direction the music wants to go,” says Greene. “We were just reviewing one of [Deepstaria’s] unreleased tracks from Phillips, and it was like, ‘Oh, wow! I forgot about that whole metal section!’ We embrace that. We know what to do when things start to careen off in that direction. It’s five composers, jointly contributing, and the whole is greater than the sum of the parts.”

That’s what makes the long drive from Minnesota worth it for Hirsh.“What I enjoy so much about playing with these guys, and why I keep coming down to Memphis, is that everybody’s ears are so wide open. It’s like you’re 10 years old, and you’re out in the woods running around playing, and somebody says, ‘Ooh! Look at this cool thing over there!’ And everybody runs off to see this cool thing over there.

“You hear people, particularly jazz musicians, talk about reflexes. But what we are talking about, I think, is a step beyond reflexes. Everybody is hearing something unfold, and it’s not that they’re reacting to something they’ve heard; it’s that they hear where it’s going. … I call it ‘real-time group composition.’ That’s my best description of it.”

Crosstown Arts presents Steve Hirsh and Friends in the Green Room on Thursday, April 24th, 7:30 p.m. Visit crosstownarts.org for details.