There are four horsemen of the gentrification apocalypse.

According to Maurice Henderson II (the founder of CxffeeBlack better known by his pen name, Bartholomew Jones), craft breweries, ladies walking their poodles, Whole Foods, and coffee shops are markers to the “gentrification population” that a community is ripe for harvesting.

For Henderson and his wife, Renata Henderson (Memphis’ first Black female coffee roaster), there’s irony in this. Coffee’s origins can be traced back to Africa, and according to Henderson, it’s the “traditional African medicine” for Southern Ethiopia, Sudan, Eritrea, and Djibouti.

“Coffee is such an amazing ritual in the motherland, but that’s not the perspective we generally see in shops that come into our neighborhoods,” says Henderson. “In fact, somehow there are spaces that are almost anti-Black. Even though coffee is literally black, and historically Black.”

Henderson dives into the history of how coffee was made into a million-dollar industry through the slave trade in Brazil, Haiti, Latin and Central America, and the Caribbean, and that West African slaves were used to grow coffee into the industry that it is today.

The irony intensifies for the couple, as they ponder how something that is historically Black, discovered by Black people, grown by Black people across the world, becomes uncommon or even “unexpected” to see Black people work with, or even be in ownership roles. Especially when these coffee shops are in Black and brown neighborhoods.

“You have these shops that are in these neighborhoods, but you don’t see anyone from the neighborhood in the shop,” says Henderson.

The Hendersons noticed that their neighborhood would be gentrified soon — the city planned on putting money into the intersection at Summer Avenue and National Street — and wanted to see what it would be like for their neighborhood to have their own coffee shop before the “gentrifiers come in.”

“It’s weird,” says Henderson. “Our neighborhood has the best Latin American food in the city — like, I will fight people about that — and yet a Chipotle just got built on Summer in our neighborhood.

“What if we created a place for us, by us? What would that look like? Could we return coffee to a tool that is actually empowering for Black and brown people, and something that supports our neighborhood? That was the experiment we started,” says Henderson.

The experiment in question manifested itself into the Anti Gentrification Coffee Club, located at 761 National Street. According to Henderson, the experiment turned into a hub for local creatives, those living in boarding houses, and local activists.

The Hendersons hired people from their community, and people who come in and fall in love with the shop. They aspired to make a safe space for their neighbors to enjoy “culturally congruent” coffee experiences.

With community playing such a large role in the Henderson’s reason for creating their coffee shop, it would seem inevitable that they valued input from the community. However, in listening to input, they recently did something that they had tried to avoid.

On the morning of October 5th, 2022, The Anti Gentrification Coffee Club opened its doors much earlier than usual at 7:30 a.m. This new opening time allowed for those on their early-morning commute to stop by and grab coffee.

Henderson’s perspective is shaped from his experiences as an educator, an indie-rapper, and a part-time barista. He says that his least favorite interactions were during early-morning shifts, where he experienced frequent micro-aggressions.

“It’s almost like ‘man, you’re not even a human being,’ when you have your stereotypical experience with someone at a coffee shop,” says Henderson.” They’re behind the bar, and people assume you don’t know what you do because you’re Black. They think people want what they want. It’s a very individualistic experience, which is so different from coffee in Africa.”

The Hendersons have been to Ethiopia twice, and even talked about their experiences in a documentary, CxffeeBlack to Africa, that will be shown at the Indie Memphis Film Festival. The defining difference between coffee in Ethiopia and what they have experienced in the states is that coffee in Ethiopia is “communal.”

“Things are slow,” explains Henderson. “They do these three processes called Abole, Tona, and Bereka, where you have these really small cups called ‘Sinis,’ and you get three cups. There’s no going into traditional African spaces and getting a big cup of coffee to go.”

Henderson explains that in Ethiopia, this process is led by Black women, where the coffee is roasted fresh, prepared, and then served.

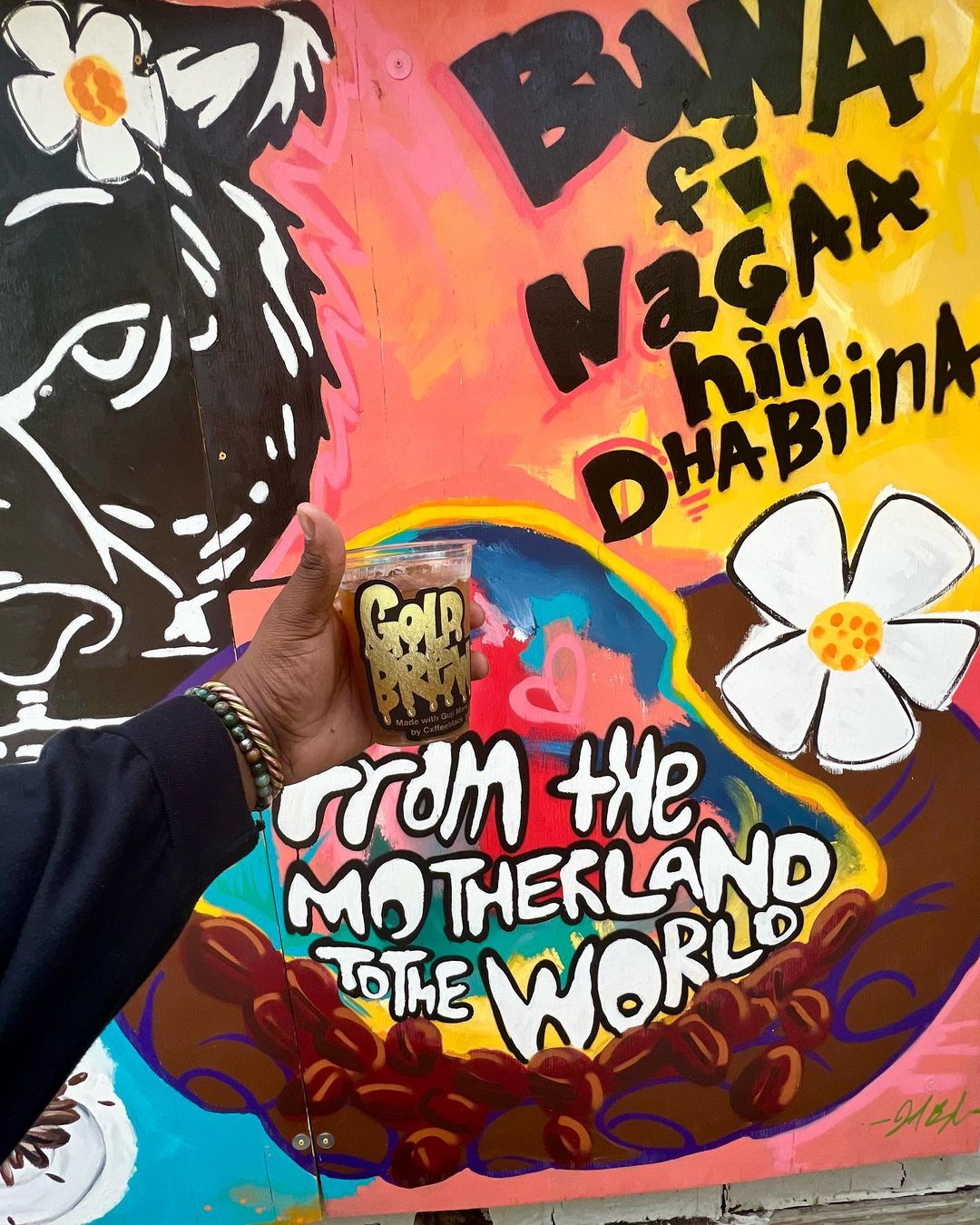

“There’s a traditional Ethiopian blessing that is said when you receive it,” says Henderson. “Buna fi Nagaa hin Dhabiinaa, which means ‘May your house lack no coffee nor peace.’ They wish peace upon you and your family. You sip the coffee, say ‘amen’ in response. You’re doing that with a group of other people who are sitting there, and waiting on coffee to be prepared for you by these Black women.”

Centering Black women as the planet’s first baristas, and coffee roasters, is something that Henderson and his team try to do, and is something that he says is “uncommon in a space.” Creating space for community and creating space for people to “slow down” is antithetical to an early rush experience at Starbucks, he says.

It’s a very transactional experience, Henderson adds. In fact, this is why they chose to not open early in the beginning, so that they could avoid contributing to these types of interactions with coffee in their neighborhood. Henderson says they would rather create a space where people expect a different type of coffee experience. They sought to have a more Black, a more African, a more indigenous perspective, and for these reasons, they opted to not open early.

Henderson says that they don’t hire traditional baristas. Instead, they hire people from their community. In hiring people from their community, they would bring the problems of the community with them.

“Transportation is an infrastructure issue in our city,” Henderson says. “Opening later allowed us to still hire the people we wanted to hire. If we say ‘you have to have a car,’ then there’s a lot of people in our neighborhood who would be left out of that.”

The Hendersons had periodically experimented with early openings, but they concluded that it was more “human forward, and human friendly,” for them to be open late.

According to Henderson, your traditional coffee shop is going to make money by getting as many people through their doors as possible. He says that through this, the people that are prioritized are wealthy patrons, or patrons that are “upper-middle class.” Coffee at his shop is pay-what-you-can with suggested prices, but “it’s free for neighbors who need it.”

“Most people have coffee as a morning routine, so your general coffee shop will have a business model where you’re really expecting to get a bulk of your revenue in that morning rush, from people who are driving to your space because of some type of brand you’ve been able to generate,” says Henderson.

“You think about these shops that open up in Black and brown neighborhoods. How are they able to get people from Germantown and Cordova to drive there early in the morning for their coffee?”

The answer, according to Henderson, is by creating some type of “chic” or “urban-chic mystique” that makes their coffee seem different from what they can get at the gas station or Starbucks. A lot of this is by using the aesthetic of poverty to market a shop as something that is “urban,” which in turn makes your coffee and shop “desirable to people who are looking for a cool ‘coffee experience.’”

“We know that Blackness is generally the arbiter of cool,” says Henderson. “So by being in proximity to Blackness, your shop obviously becomes cool.”

Henderson says that the issue with this is that there is no actual care for the Black people in these neighborhoods. He says that the aesthetic and sexiness that comes from the sense of “Oh, this is dangerous. I’m driving through an urban community. Oh, this is cool, this is artistic,” is being used to drive sales, but the people in these communities are not being considered as possible customers.

“There’s a myth that Black people don’t drink coffee,” says Henderson. “Through our e-commerce store, we’ve been able to build a multiple, six-figure business just from selling coffee to Black folks online. You know, the roasted coffee that my wife roasts. So obviously, this isn’t true.”

Henderson says that a lot of times, there’s a certain type of coffee, one that differs from Folgers, but is rather a more “craft coffee experience,” that many Black people have not been introduced to.

“We wanted to see what it would look like for us to make a coffee experience that would allow for people to taste these really exotic coffees from all over the world, coffees that come from our motherlands, but in a way that is conducive for Black culture to thrive, and not have assimilate,” he says.

Michael Donahue

Michael Donahue