In First Man, Neil Armstrong (Ryan Gosling) is talking to his kids the night before heading to Cape Canaveral, where he will launch for the moon. His son Rick (Luke Winters) asks him if he’s sure he will make it to the moon and back. “A lot of things have to go right for that to happen,” he replies.

Armstrong was an Ohio farm boy and Eagle Scout who took his first solo flight before he learned to drive a car. He enrolled in college with the help of a Navy reserve scholarship just in time to be called up to fly close air support in Korea. After the war, he became a test pilot, putting the latest and fastest experimental aircraft through their paces, and waiting for something to fail.

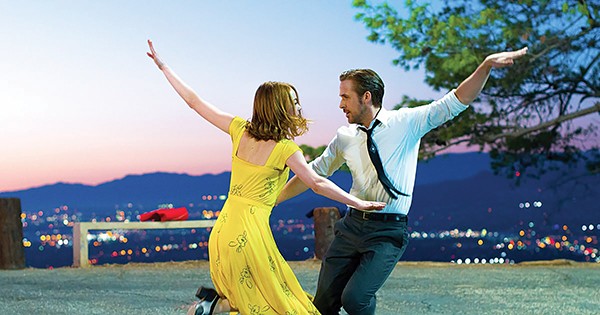

Ryan Gosling as Neil Armstrong in First Man

That’s where First Man picks up Armstrong’s story. In a riveting opening sequence, fraught with foreshadowing, he flies the X-15 rocket plane to the edge of space, then bounces off the atmosphere when he tries to return home. It’s only his quick thinking and superhuman calm that save him.

But once on the ground, the mastery he feels in the cockpit is rudely dispelled by reality. His two-year-old daughter Karen is dying of a brain tumor, and even though he brings the same scientific discipline and rigor to her treatment, there’s nothing he can do to save her. Neil and his wife Janet’s (Claire Foy) formerly strong relationship is strained to the breaking point by their daughter’s death, so he pours everything into his work — which soon means beating the Russians to the moon.

Armstrong is that greatest rarity in our fake age: an authentic hero. He was by all accounts exactly what he appeared to be, a sincere science geek who took his position as a role model seriously, even though he didn’t seek it out. After retiring from NASA, Armstrong chose to teach at the University of Cincinnati, the American city named for the early Roman general who refused the allure of dictatorial power and returned to tend his farm once the wars were through. After the moon landing, Armstrong was the most famous and respected person in the world. He could have, like fellow Ohioan John Glenn, parlayed his fame into a political career. Instead, he taught undergrads science at an underfunded public university. That alone sets him apart from the borderline sociopaths today’s big budget Hollywood productions portray as heroes.

Armstrong probably wasn’t cut out for politics outside NASA, though. A running gag in First Man has him ignored at Washington parties and bombing at press conferences, where he has to be bailed out by the bombastic Buzz Aldrin (Corey Stoll). In his element, Armstrong was eloquent and concise. Gosling’s greatest moment is when the NASA selection committee asks him why we should travel into space, and his stoic exterior slips as he talks about the need to change our earthbound perspective.

Gosling, who does “Midwest reserve” better than anyone, was born to play Armstrong, His performance is matched by Foy as a woman who has been to way too many funerals. Other standouts in the cast include Kyle Chandler as Chief Astronaut Deke Slayton and Christopher Abbott as Dave Scott, who almost dies in orbit with Armstrong when the Gemini 8 mission goes spectacularly wrong.

Directed by Damien Chazelle, First Man boasts some incredible set design and art direction. The NASA offices are bleak, utilitarian government buildings, while the space capsules are incredibly complex, handmade deathtraps. For the spaceflights which form the film’s backbone of set pieces, Chazelle keeps things mostly restricted to Armstrong’s point of view, where the rockets roar, the metal groans and creaks, and wonders lurk just outside the tiny window. And it works, for the most part.

Like the moon shot, a lot of things have to go exactly right for a giant

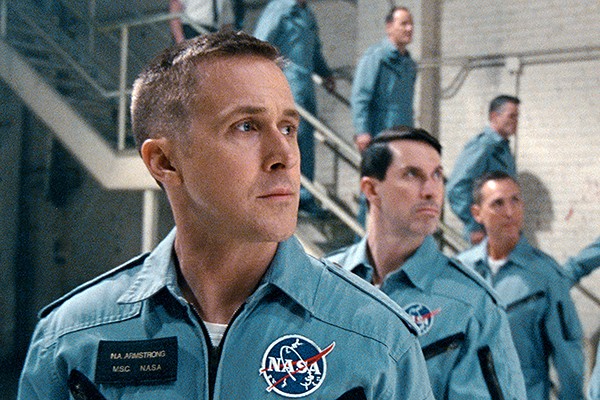

biopic like this to take off. Unfortunately, First Man suffers from a major systems failure. The cinematography, credited to Linus Sandgren, undermines the solid script, good performances, and exquisite art design. First Man is shot in multiple formats (16 mm, 35 mm, and IMAX) which are combined haphazardly at best. Long stretches of the film are done in intentionally shaky handheld camera that is just plain bad. You can hold your iPhone steadier than these professional camera operators manage while just shooting two characters walking down the street, having a conversation. It’s especially baffling coming from Chazelle, whose last film, La La Land, was one of the most visually rigorous of the decade. That means rendering intimate domestic scenes like they were battles in The Hunger Games was a deliberate, nauseating choice. There are flashes of brilliance in First Man, but like the stuck thruster that almost killed Neil Armstrong before he ever got to the moon, the shoddy photography sends the whole thing spinning out of control.