Damien Echols, a host of attorneys, and two advocacy groups have appealed to the Arkansas Supreme Court to allow for testing of evidence in the West Memphis Three (WM3) case.

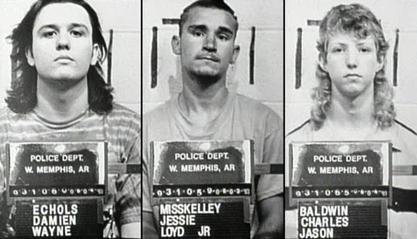

The West Memphis Three includes Echols, Jason Baldwin, and Jessie Misskelley. The three were arrested and convicted in the ’90s as teenagers in West Memphis, Arkansas, for the murders of three young boys — Steve Branch, Christopher Byers, and Michael Moore. The WM3 were released in 2011 with an Alford plea, a guilty plea that allowed them to go free and maintain their innocence.

Since then, Echols and a legal team have been searching for who they say are rightfully responsible for the murders. A year after their release, for example, the group offered a $200,000 reward for any new information that might lead to the real killer or killers.

In 2020, Echols and his attorney secured the release of evidence in the case for testing. They wanted to use a new technology, the M-Vac DNA system, that was not available at the time of the original crime to probe for new evidence.

In December 2021, Echols’ attorney Patrick Benca of Little Rock visited the West Memphis Police Department and found that all of the evidence — once rumored to have been destroyed in a fire — was all there and intact.

This included the target of that new testing, the young boys’ shoelaces that had been used to tie their arms and legs. It also included the victims’ shoes, socks, Boy Scouts cap, shirts, pants, and underwear, and the sticks used to hold the clothing underwater. The team had even chosen a lab to perform the testing, Pure Gold Forensics in California.

However, officials changed their minds on releasing the evidence. Through a series of legal challenges since then, Arkansas officials have continued to block Echols’ access to the evidence.

In January, Echols’ team of lawyers appealed to the Arkansas Supreme Court for the right to the evidence. National advocacy groups, The Innocence Project and The Center on Wrongful Convictions, filed motions friendly to Echols’ cause in the matter.

They are fighting a number of legal arguments made by Arkansas officials that claim Echols did not file previous suits in the right courts, that he does not have the right to see the evidence because he is not in prison, and more.

But Echols’ teams says the testing is, fundamentally, about public safety.

“After all, if innocent persons have been wrongfully convicted, then the guilty persons have obviously not been convicted,” reads the January appeal. “Take this case for example. If, as they have steadfastly maintained for almost three decades now, the WM3 did not commit these murders, then the person(s) who did so remains in the community — murderers at large, putting us all at risk.”

However, Dylan Jacobs, the deputy solicitor general in the Arkansas attorney general’s office, said in a May brief that Echols should not have this right, arguing Echols has already used up plenty of the state’s time and resources.

“Yet over a decade after his release, Echols now seeks to further waste judicial resources to challenge the conviction he negotiated for,” Jacobs wrote. “He should not be allowed to. The [Arkansas] General Assembly made post-conviction DNA testing available to set free innocent prisoners, not recenter the limelight on freed felons.”

For the last part, at least, Echols’ attorney said in a late-May rebuttal that “nothing could be further from the truth.” The timing of the new petition, he said, was based on new technology, not on “the state’s hypothesized interests.”

That brief ends with a pointed conclusion.

“It is evident from the state’s brief how bitterly the Attorney General’s Office feels toward Echols,” it reads. “But how would it feel if new DNA testing identified an individual other than Echols as the perpetrator of these crimes?

“Would it celebrate the criminal justice system’s correction of a horrible error? Or, would it bemoan the loss of its trophy conviction of Echols and the West Memphis Three? The answer unfortunately seems readily apparent, albeit one contrary to the public prosecutor’s role to ensure ‘that justice shall be done … guilt shall not escape or innocence suffer.’”

The Innocence Project has started a global petition for support to help Echols bring his case to the court.