Courtesy Memphis Music Hall of Fame

Courtesy Memphis Music Hall of Fame

Scott Bomar & Don Bryant

This past Friday evening in downtown Memphis, Tennessee, the Memphis Music Hall of Fame honored some of music’s most influential singers and songwriters at its eighth annual Induction Ceremony.

The event honored eight Memphis-area musicians whose lifetime contributions to music embody elements of the “Memphis Sound,” all central figures in the history of chart-topping music of the 20th Century.

The official nexAir Stage at the Cannon Center for the Performing Arts was filled with luminaries, both presenting and receiving the night’s distinctions. This year’s roster of inductees was an impressive and diverse group: Don Bryant, Dee Dee Bridgewater, Charlie Musselwhite, The Memphis Boys, Steve Cropper, Dan Penn, Tina Turner, and perhaps the most surprising, posthumous inductee and “The First Lady of Grand Opera,” Ms. Florence Cole Talbert-McCleave.

McCleave was an American operatic soprano and one of the very first black female opera singers to receive acclaim and critical success in the 20th Century, as well as one of the first to record commercially. Though not originally from Memphis, it was here she eventually settled and during her time was a sought-after performer, trailblazer for African-American women, and active educator for young black musicians throughout Memphis, even co-founding the Memphis Music Association. It is a testament to their scope that the Memphis Music Hall of Fame has opened its arms to classical forms of music like opera: the tribute performance to McCleave, an excerpt from “Aida” by soprano Michelle Bradley, was second-to-none and, quite simply, breathtaking.

Courtesy Memphis Music Hall of Fame

Courtesy Memphis Music Hall of Fame

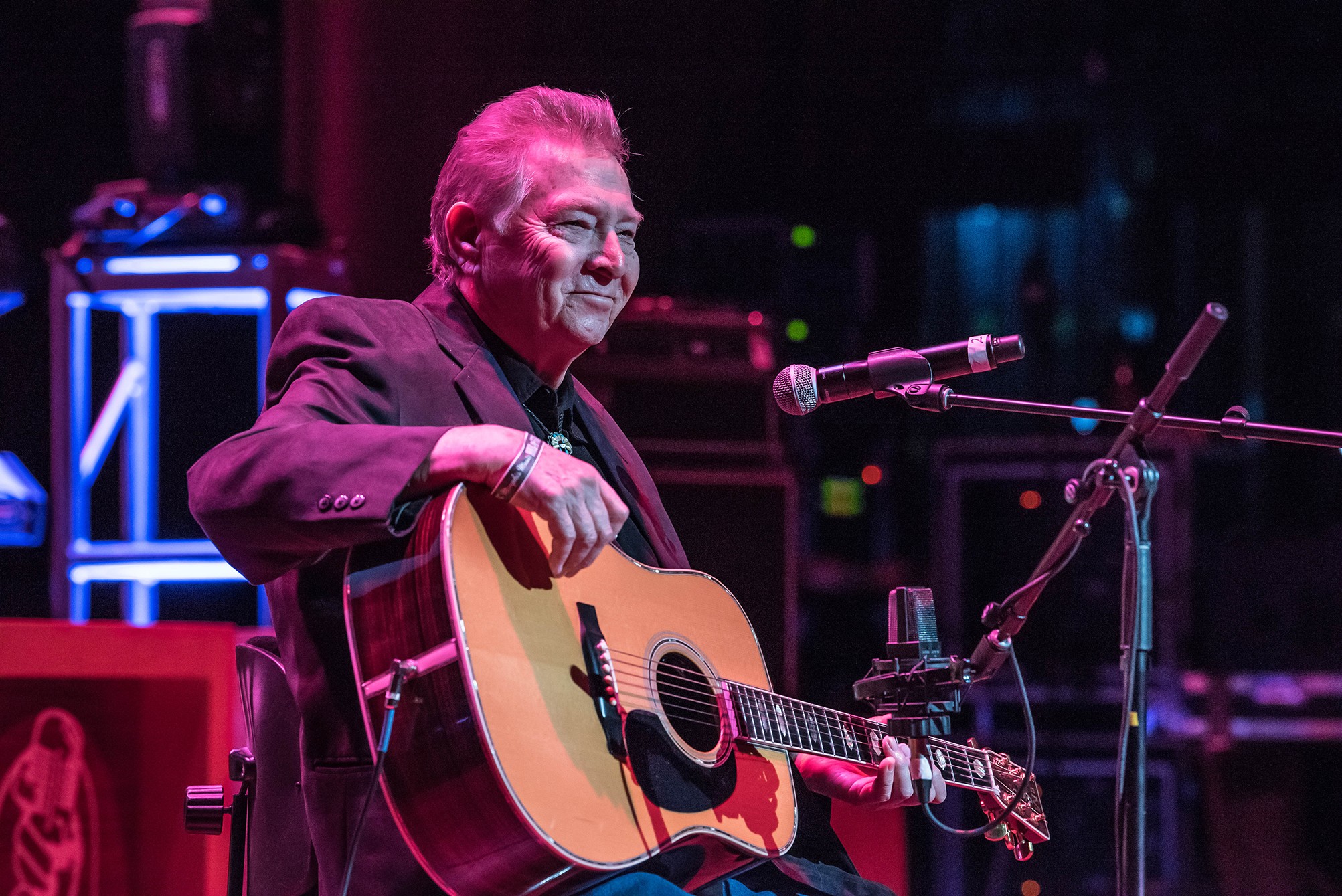

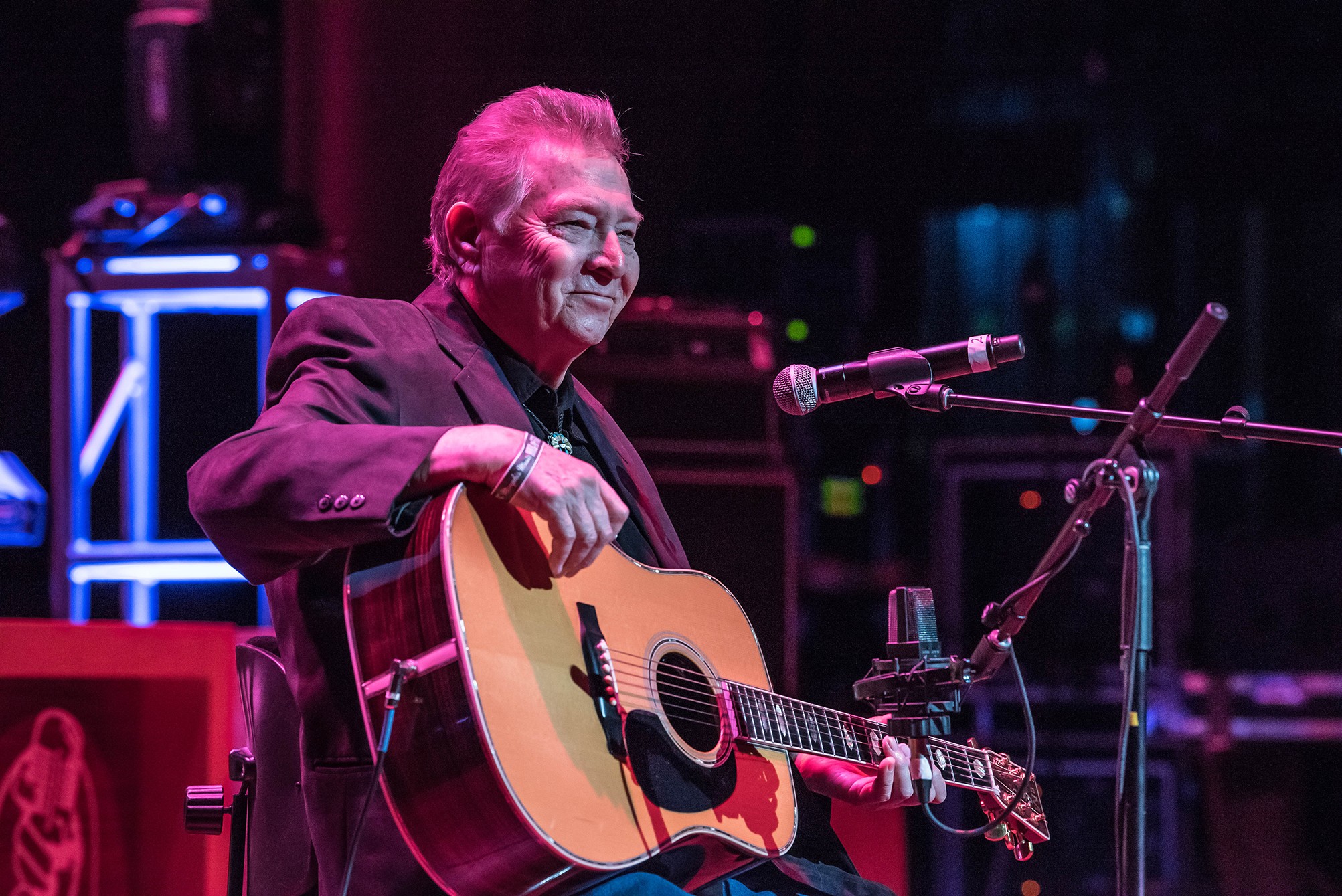

Don Bryant

Next up was Don Bryant, house songwriter for Willie Mitchell’s Hi Records throughout the 60s and 70s, husband to singer Ann Peebles, and gifted singer in his own right. Bryant is the rare combination of sincerely disarming, winsome, and talented. Backed by a bevy of some of the finest working musicians in Memphis, the Bo-Keys, Bryant let shine from that stage his unparalleled smile and inventive, heartfelt vocals. The Bo-Keys, who now tour regularly with Bryant, included: Joe Restivo on guitar, Scott Bomar on bass, Marc Franklin and Kirk Smothers on horns, Archie “Hubbie” Turner on keys, and the Memphis “Bulldog” himself, Howard Grimes on drums. The latter two bandmates, with Bryant himself, served as key members of the house band at Mitchell’s Royal Recording Studios, playing on some of Hi’s most celebrated recordings of the era.

One of the eight inductees was actually a group award. Six session musicians made up The Memphis Boys, the house band at legendary producer Chips Moman’s American Sound Studio, comprised of drummer Gene Chrisman, bassists Tommy Cogbill and Mike Leech, guitarist Reggie Young, pianist Bobby Wood, and organist Bobby Emmons. Together these men laid down the grooves for over 120 hit records between 1967 and 1972 for artists like Aretha Franklin, Wilson Pickett, B.J. Thomas, Dusty Springfield, and notably, on Elvis Presley’s last number one hit “Suspicious Minds.”

Courtesy Memphis Music Hall of Fame

Courtesy Memphis Music Hall of Fame

Extended family of The Memphis Boys

Of the remaining members, keyboardist Bobby Wood gave a sincere thanks to the city of Memphis while drummer Gene Chrisman audibly held back tears of gratitude as he accepted his award, and in an endearing moment of appreciation of those years he reminisced, “I’ll tell you it was such a pleasure…We had more fun than two Christmas monkeys.”

As the room bubbled with cheer and nostalgia, the house band and guest singers led a medley of the Memphis Boys’ greatest hits: “Raindrops Keep Falling on My Head,” “Hooked on a Feeling,” “Son of A Preacher Man,” “Suspicious Minds,” and “Sweet Caroline,” among others.

Courtesy Memphis Music Hall of Fame

Courtesy Memphis Music Hall of Fame

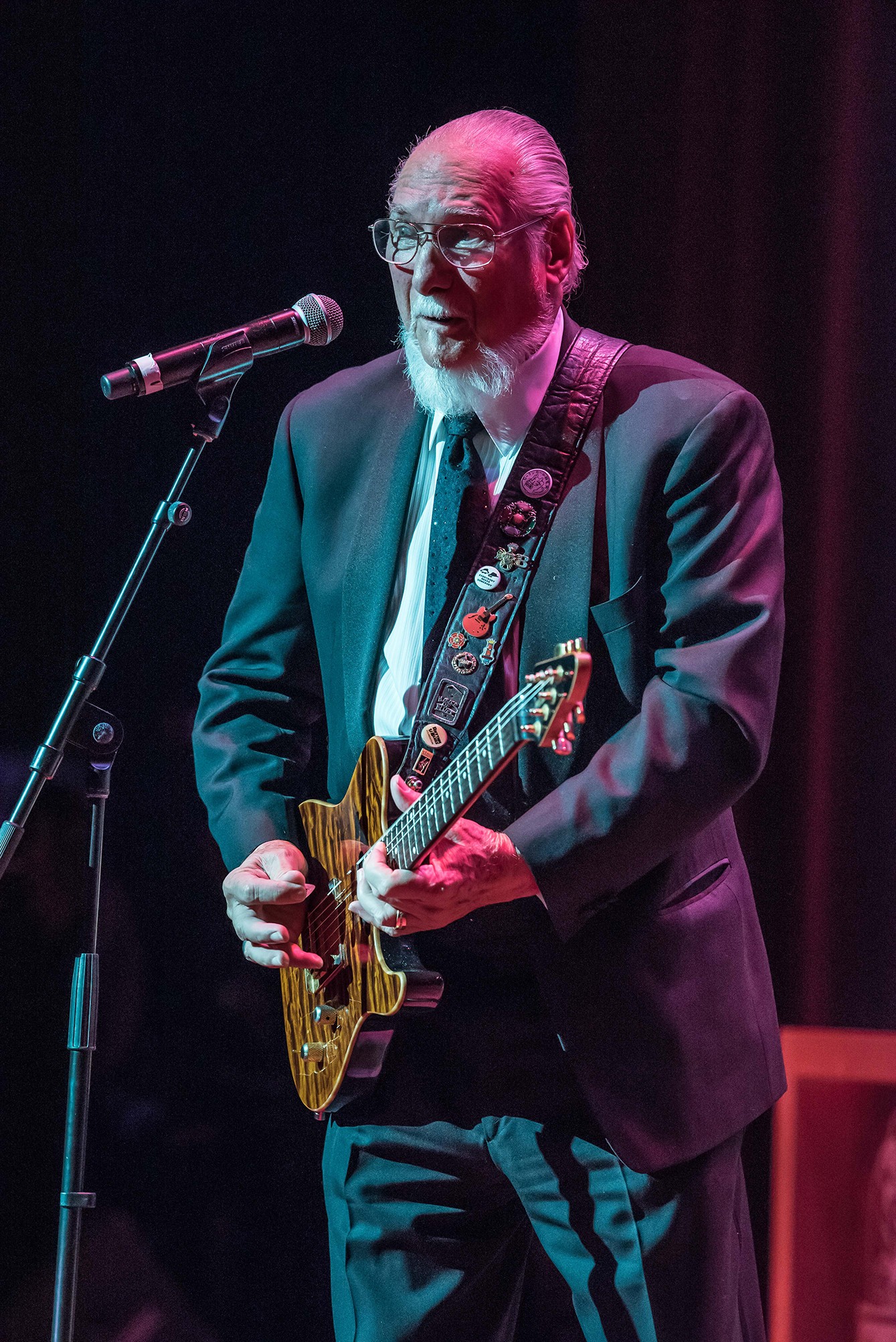

Charlie Musselwhite and Bobby Rush

Boundless blues entertainer Bobby Rush introduced his erstwhile touring partner, friend and Grammy-winning electric blues heavyweight Charlie Musselwhite. Charlie, gracious as always, serenaded us with his famous harmonica stylings on “Blues Overtook Me.”

It was a night of montages, as rapper Al Kapone stepped out to speak with an unexpectedly heartfelt appeal to support live Memphis music. As he stepped aside, dueling DJs live-mixed an audio mosaic of some of the most cherished hits to come from our city: “Hound Dog,” “Great Balls of Fire,” “Gee Whiz,” “Pretty Woman,” “Hold On I’m Coming,” “Soul Man,” “Shaft,” “Love and Happiness,” “Ring My Bell,” and many others, on through more modern Hip-hop hits like “Hard Out Here for a Pimp.” This was followed by a brief but thoughtful “In Memoriam” video paying tribute to those Memphians in music we’ve recently lost.

Courtesy Memphis Music Hall of Fame

Courtesy Memphis Music Hall of Fame

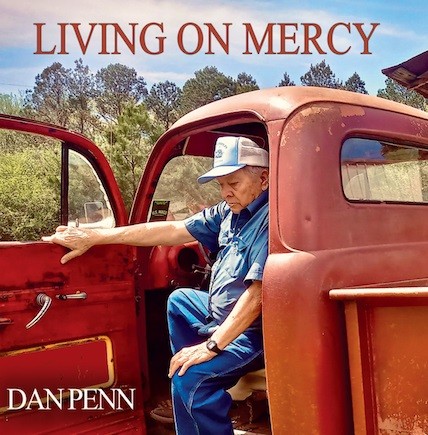

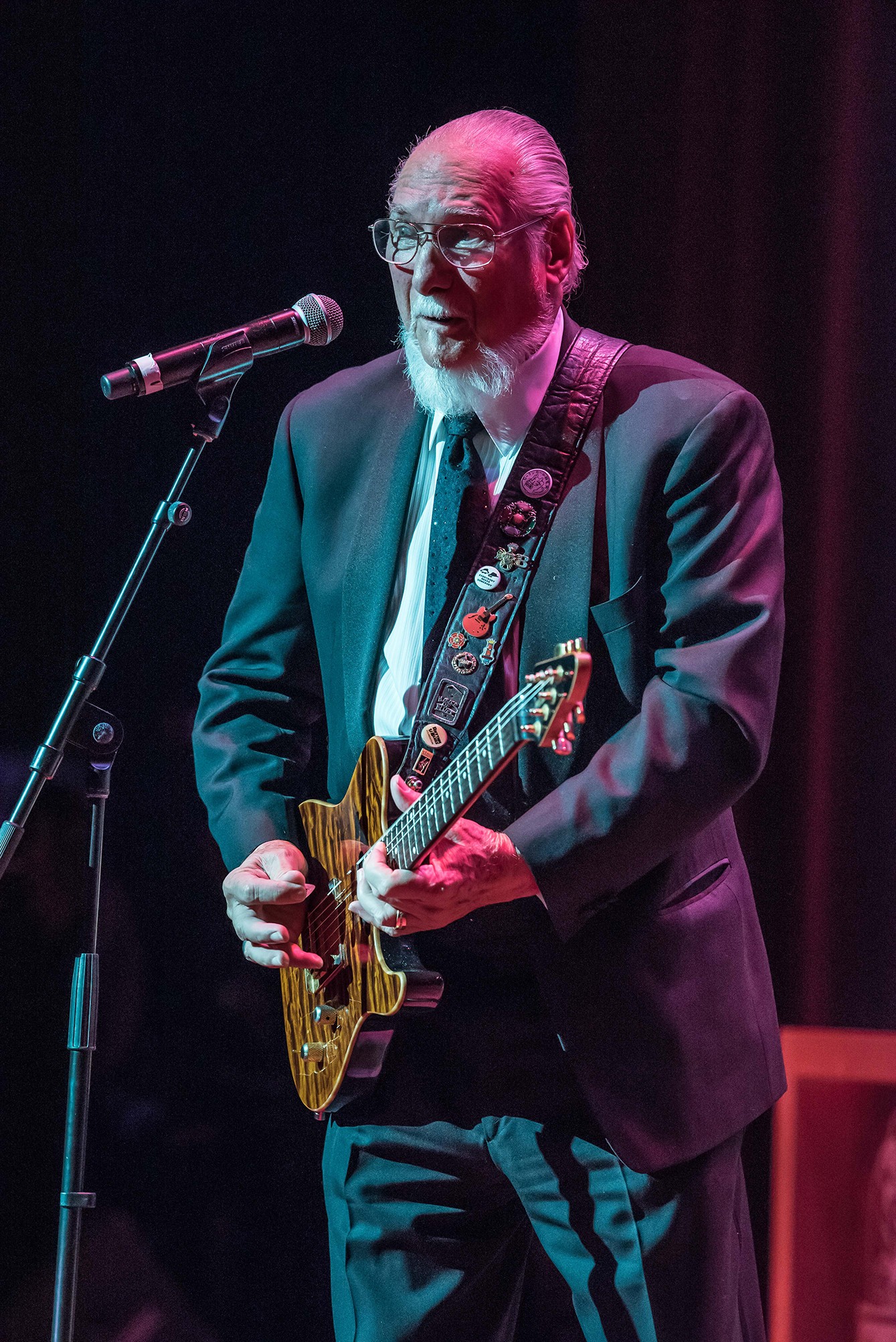

Dan Penn

Grammy-winning producer Matt Ross-Spang presented the next inductee, composer, instrumentalist, and singer Dan Penn. One of the most prodigious songwriters to come out of the Shoals, Penn’s songs possess a permanence that not many can boast – most famed among them, Aretha Franklin’s “Do Right Woman, Do Right Man” and The Box Tops “Cry Like A Baby.” Penn gave a brief and witty acceptance and returned to play another of his seminal hits, “The Dark End of the Street,” a hit for James Carr on Goldwax in 1967. At 77, Penn’s stunning voice still commands a standing ovation.

Native Memphian and dynamic singer Dee Dee Bridgewater got her well-deserved accolades from Royal Studios’ Boo Mitchell, son of legendary producer Willie Mitchell. Mitchell spoke of the recent work he has done with Ms. Bridgewater on her last record Memphis… Yes, I’m Ready, and ready she was: attired in glittering silver from head to toe, Bridgewater dazzled and shone. The jazz singer, Broadway star, and Grammy-winner addressed her Memphis roots and mesmerized the audience with her rousing rendition of “Can’t Get Next to You.”

Courtesy Memphis Music Hall of Fame

Courtesy Memphis Music Hall of Fame

Steve Cropper

Blues guitarist and brother to the late Stevie Ray, Jimmie Vaughan introduced the incomparable Steve Cropper. Guitarist, songwriter, producer, Stax house guitarist, and OG “G” of Booker T. & The M.G.’s, he’s responsible for some of the greatest songs ever recorded, having written for and worked with everyone from Otis Redding to John Lennon. Inducted in 2012 as a member of Booker T. & The M.G.’s, this year saw him inducted as a solo artist for his life-long accomplishments, and, a natural charmer, he treated us to a version of his Redding co-write “(Sittin’ On) the Dock of the Bay,” leading the audience through whistles at the end.

The final inductee of the night was to a lady born Anna Mae Bullock in nearby Nutbush, Tennessee, and known to the world as Miss Tina Turner. Though not present at the ceremony, we enjoyed an agreeable medley of her greatest hits to round out the festivities, performed by a collection of local female artists who did Miss Turner proud: “Rock Me Baby,” “What’s Love Got To Do With It,” “We Don’t Need Another Hero,” and “River Deep, Mountain High” among others.

Memphis is a town chock full of heavy contributions to the music world – and these ceremonies, presenting so many timeless artists and songs in one sitting, are mind-blowing. It was a night of sheer celebration and a night of sober reflection. It was, as Chrisman mused with his distinct Southern drollness, ‘more fun than two Christmas monkeys.’

Courtesy Memphis Music Hall of Fame

Courtesy Memphis Music Hall of Fame  Courtesy Memphis Music Hall of Fame

Courtesy Memphis Music Hall of Fame  Courtesy Memphis Music Hall of Fame

Courtesy Memphis Music Hall of Fame  Courtesy Memphis Music Hall of Fame

Courtesy Memphis Music Hall of Fame  Courtesy Memphis Music Hall of Fame

Courtesy Memphis Music Hall of Fame  Courtesy Memphis Music Hall of Fame

Courtesy Memphis Music Hall of Fame

courtesy Swain Schaefer Memorial Page

courtesy Swain Schaefer Memorial Page