Early in the 2015 documentary Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, Cobain’s aunt Mary says offhandedly, “I’m glad I wasn’t born with the genius brain.”

Artists, scientists, inventors, and creatives of all sorts have a long history of struggling to fit in. Maybe because their creative drive, rooted in a need for novelty, renders them allergic to the ordinary world. To do your best work, sometimes you have to put the world at arm’s length and follow your muse where it leads you. But for those stuck in the ordinary world, this can be very irritating.

Reynolds Woodcock (Daniel Day-Lewis) definitely has the genius brain. His House of Woodcock is the best and most prestigious haute couture establishment in postwar London. His clients include the rich, famous, and royal. His fangirls tell him they want to be buried in one of his dresses. Reynolds was taught his trade by his mother, whom he and his spinster sister Cyrill (Lesley Manville) idolize long after her death. Cyrill acts as a kind of gatekeeper and manager to Reynolds. The attention to detail that has brought him fame and fortune comes with a side order of obsessive compulsive disorder. Reynolds is the human incarnation of the word “persnickety.”

Woodcock has had a string of girlfriends who he keeps around until he tires of them and Cyrill runs them off. One day, he’s having breakfast at a quaint restaurant near his country home when he sees a beautiful waitress named Alma (Vicky Krieps). He asks her out in a most unusual way, and soon she is living with him and Cyrill. Their relationship eventually evolves into a three-way battle of wills, with Alma striving to get closer to Woodcock, while Cyrill tries to maintain her grip on her brother.

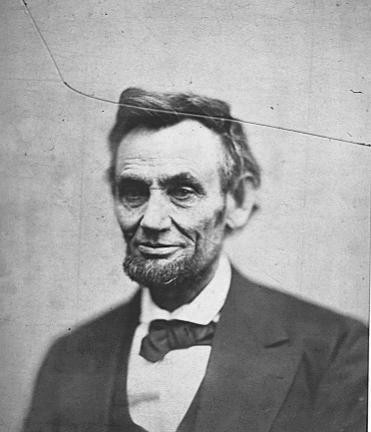

Daniel Day-Lewis (left) and Vicky Krieps tangle their lives in Paul Thomas Anderson’s new film about fashion and passion, Phantom Thread.

Phantom Thread is writer/director Paul Thomas Anderson’s eighth film, and if there’s one thing you can say about Anderson’s career, it is that he never does the same thing twice. Another thing you can say about Anderson is that his work can be divisive. Boogie Nights, Punch Drunk Love, and There Will Be Blood enjoyed near universal acclaim, but as for Magnolia, The Master, and his last film, Inherent Vice, well, you either love them or you hate them. Personally, I loved Inherent Vice, which puts me in the minority, and I can’t stand Punch Drunk Love, which alienates me further. So, for me, Anderson is hit or miss.

Day-Lewis, who earned a Best Actor Academy Award in There Will Be Blood, is pretty brilliant as Reynolds, the kind of guy who wears a blazer and vest over his pajamas. He cannot be satisfied, even by success. The day before a beautifully sewn royal wedding dress is to be shipped off he declares it “ugly.” His relationship with Alma plumbs new depths of passive aggression. But Alma gives as good as she gets, and maybe since she is the first person to ever stand up to him, he can’t let her go, even when their affair becomes life threatening.

As usual with Anderson’s work, the cinematography is meticulous and excellent. Alma and Reynolds’ love story is exceedingly chaste, which is remarkable given that the director is most famous for his ode to the pornography industry. The porn urge is redirected toward the clothes, with loving closeups of lace and sewing fingers. The most erotic it gets is a measuring session that borders on the sadomasochistic. The film’s deep obsession with accoutrement reminded me strongly of the work of Memphis director Brian Pera, while the claustrophobic atmosphere of social obligation and niceties lends a strong Barry Lyndon vibe.

Perhaps Phantom Thread is best understood as the director coming to grips with his own genius brain. It’s probably too simplistic to say Reynolds is a stand in for Anderson’s perfectionism, but the director clearly sympathizes with him. What makes this film stand out is that he also sympathizes strongly with Alma. In this “Me Too” moment, it seems that the myth of the Byronic, bad boy artist is crumbling, and that’s probably for the best. Lewis, who says he’s retiring from acting after this film, will grab all of the attention, but it’s Alma’s fight to bring Reynolds back into the real world that will resonate.