The most crucial visual moment of Nope comes disguised as a simple establishing shot. It’s easy to miss it in the tornado of arresting images and brutal scares that make up Jordan Peele’s explosive deconstruction of the alien-invasion genre.

Take the opening shot, for example. A girl’s shoe stands upright, toes pointed to the ceiling of what is revealed to be the set of a ‘90s era sitcom. A pair of feet — one of which the shoe apparently belonged to — protrude, unmoving, from behind a blood-splattered couch. A chimpanzee emerges, wearing a pointed birthday party hat. Blood drips from its mouth; its hands are covered in viscera. The enraged primate scans the room until it seems to notice the camera. It looks directly at the audience for a horrible moment. Then, the bloody chimp comes at us with murder in its eyes.

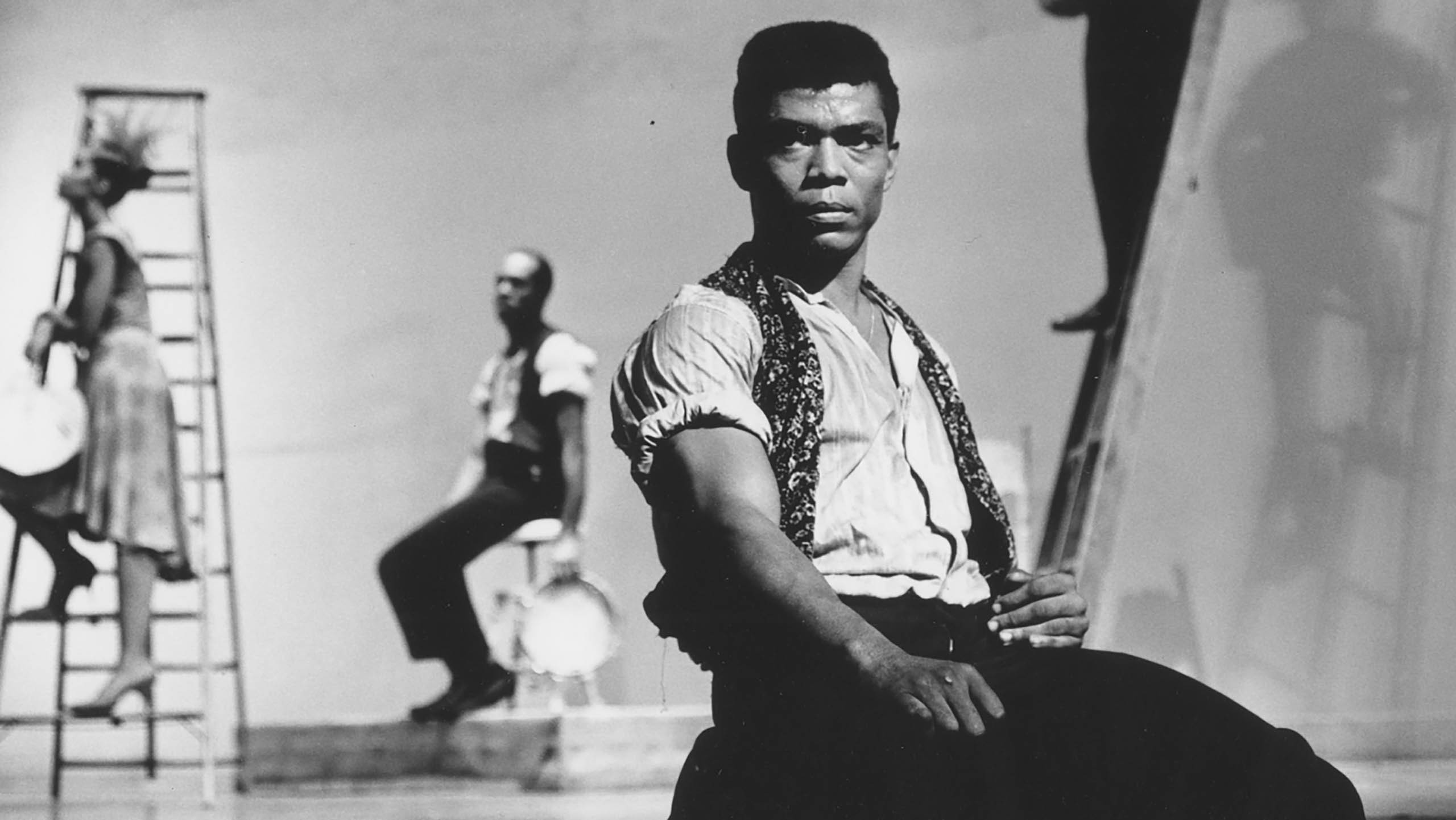

We later learn that the chimp was looking at Ricky “Jupe” Park, played as a child by Jacob Kim and as an adult by Stephen Yeun. Jupe was a child star of a Western TV show called Kid Sheriff. Then he was cast to co-star with a friendly chimp in a Family Ties-type sitcom called Gordy’s Home. One day, Gordy the chimp got fed up with all these humans telling him what to do and murdered the cast while the cameras were rolling. Only Jupe escaped unscathed. Now grown, Jupe runs a dude ranch called Jupiter’s Claim. The rootin’ tootin’ wild west shows he mounts in the dinky amphitheater allude to his Kid Sheriff days, but Jupe knows most of the people paying admission are there to see the kid who was in the room when the angry ape ate people’s faces on live TV.

On the other end of the California valley is Haywood Hollywood Horses, a sprawling ranch where Otis Haywood (Keith David) raises and trains horses for TV and movie stunt work. When Otis is killed by a mysterious rain of objects from the sky, his son OJ (Daniel Kaluuya) tries to keep the family business afloat with the help of his sister Emerald (Keke Palmer). But when his star horse Lucky acts up on set in front of legendary cinematographer Antlers Holst (Michael Wincott), business dries up and he’s forced to start selling his horses to Jupe.

Meanwhile, back at the ranch, something’s lurking in the sky. OJ and Emerald catch fleeting glimpses of a flying saucer which seems to be abducting their horses. Between puffs of “that Hollywood weed,” Emerald hatches a plan: They will take the first photographs of an alien spaceship — not just a bright smudge on a Navy gun camera, but a clear, definitive picture the media will go wild for: The Oprah Shot. They enlist Angel Torres (Brandon Perres), a tech support guy at a big-box electronics retailer, to help them wire the ranch with cameras. But in true flying saucer fashion, their quarry proves elusive. The trio comes up with increasingly elaborate schemes to trick the alien visitors into a photo op, eventually convincing Antlers to help them get the shot, as their close encounters get more dangerous.

The alien arrival is announced by the failure of the ranch’s electronic devices. To track the saucer, Emerald and OJ set up dozens of air dancers — those weird sock-like things roadside businesses use to attract attention — across their sprawling ranch. When one of them stops working, they know the UFO is near. Here’s where the director drops his thesis image: Peele’s cinematographer, Hoyte van Hoytema, slowly pans his IMAX camera across the valley, where legions of writhing bodies plaintively reach for the sky, hoping to attract the attention of a spaceship that will sweep them away to immortality.

Those air dancers are us, obsessed with what used to be called fame, but which social media and the quiet desperation of late-stage capitalism has reduced to simple attention. It doesn’t matter if it’s an irresistible TikTok dance, a selfie you took while storming the Capitol, or definitive proof that we are not alone in the universe. All that matters is that people are paying attention to you.

The film trade, modern fame’s crucible, is not spared from Peele’s stiletto satire, but as in his masterpiece Us, the director’s targets are much broader. Peele’s been compared to Hitchcock and Carpenter, but Nope finds him channeling Jaws and Close Encounters of the Third Kind without mindlessly aping them. When Spielberg menaced Roy Neary’s truck with an alien light show, Neary stuck his head out the window to get a better view. When OJ finds himself in a similar situation, he locks the door. Where Spielberg sees cosmic wonder, Peele sees existential horror.

Nothing in a Peele joint is ever what it seems on the surface, but none of the high-minded stuff matters unless the film works on a visceral level. The director teases and baits his audience with misdirection before unleashing a literal tornado of blood. As he pulled the rug out from under me for the umpteenth time, I sat in the theater muttering “Jordan Peele, you magnificent bastard.”

Nope is now playing in theaters.