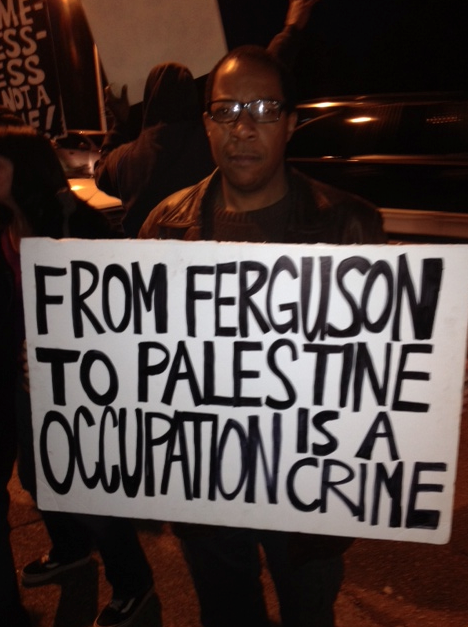

Protests were organized across the country last week, following a Ferguson, Missouri, grand jury’s decision to not indict police officer Darren Wilson in the August killing of unarmed 18-year-old Michael Brown.

Some in Ferguson held peaceful protests. But others looted and vandalized local shops and burned buildings and cop cars. In other areas of the country, including Memphis, demonstrations in opposition to the decision remained peaceful.

Louis Goggans

Louis Goggans

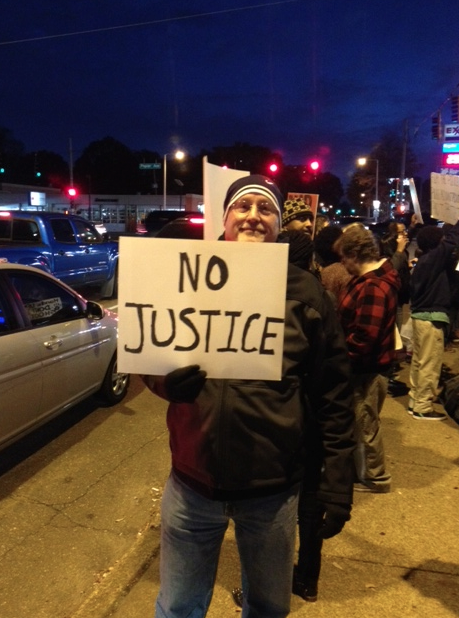

A protester at the Ferguson solidarity demonstration in Memphis last week

On Tuesday, November 25th, more than 100 people gathered at the intersection of Poplar and Highland, holding signs and chanting. Jordan Brock, a 24-year-old University of Memphis student, was among the peaceful group of protesters. However, he said he didn’t feel like the local protest would bring change.

“I was under the impression that we were going to march somewhere to try to talk to some kind of public official [and] get some answers to prevent a Mike Brown [incident] happening in Memphis,” Brock said. “But no, it was just us with signs on the intersection making good chants every five minutes. I understand that everybody wanted to be a part of a movement, but there’s no point of doing that if you don’t know what you’re protesting about.”

On August 9th, Wilson, 28, reportedly stopped Brown and his friend Dorian Johnson as they walked down the middle of a two-lane street in Ferguson. While in his Chevrolet Tahoe police vehicle, Wilson requested the two get on the sidewalk. After an exchange of words, a tussle ensued in the SUV between Wilson and Brown.

During the struggle, Wilson’s weapon was unholstered and discharged inside his SUV, according to reports. After being grazed in the hand by one of the bullets, Brown reportedly ran away from Wilson, who pursued him.

But at some point, Brown allegedly stopped running, turned around, and charged toward Wilson, according to Wilson’s account of the story. Subsequently, Wilson fired 10 shots, several of which struck Brown in his head, chest, and right arm, killing him.

Despite avoiding indictment in the shooting, Wilson resigned from the Ferguson police department on Saturday. He attributed his resignation to being concerned about his continued employment jeopardizing the safety of colleagues.

Although locals have focused attention on Ferguson, numerous controversial police-involved shootings have taken place over recent years in Memphis.

Following the December 2012 death of Martoiya Lang, a police officer who was fatally shot while serving a search warrant at an East Memphis home, several people were shot by Memphis police officers.

Memphis attorney Howard Manis is the defense attorney for the families of two of those victims: 24-year-old Steven Askew and 67-year-old Donald Moore. Both families have filed lawsuits against the MPD and city of Memphis, alleging civil rights violations.

On January 11, 2013, Memphis police officer Phillip Penny fatally shot Moore with an assault rifle at his Cordova home. Penny alleged that Moore pointed a gun at him and several Memphis Animal Services employees who were there to serve an animal cruelty warrant.

A week later, on January 17th, Memphis police officers Ned Aufdenkamp and Matthew Dyess shot and killed Askew as he sat in his car in the parking lot of the Windsor Place Apartments. The officers shot Askew nine times after he allegedly pointed his handgun at them.

Manis said with police-involved shootings occurring locally as well as across the nation, it’s imperative for officers to receive additional training on how to handle people of all races during intense situations.

“We shouldn’t be afraid of the police, and the police shouldn’t be afraid of us,” Manis said. “No matter what the color of our skin, what neighborhood we live in, the way we dress [or] act, no one should make generalized assumptions about people and then act solely based on those assumptions.”

According to Memphis Police Department policy, “Officers shall use only the necessary amount of force that is consistent with the accomplishment of their duties, and must exhaust every other reasonable means of prevention, apprehension, or defense before resorting to the use of deadly force.

“Officers are authorized to use deadly force in self-defense if they have been attacked with deadly force, are being threatened with the use of deadly force, or has probable cause and reasonably perceives an immediate threat of deadly force. An officer can also use defense if a third party has been attacked with deadly force, is being threatened with the use of deadly force, is in danger of serious bodily injury or death; or where the officer has probable cause and reasonably perceives an immediate threat of deadly force to a third party.”

St. Louis Public Radio

St. Louis Public Radio  Louis Goggans

Louis Goggans