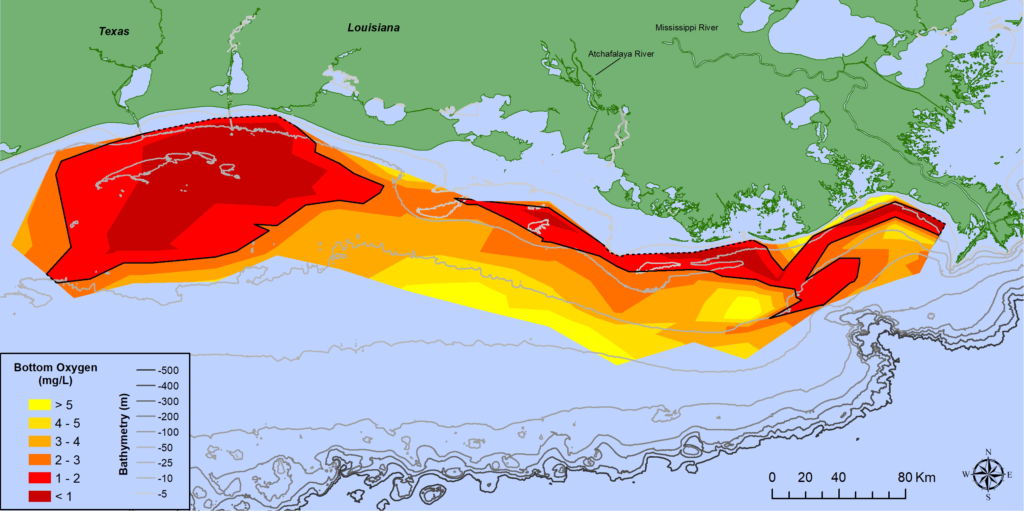

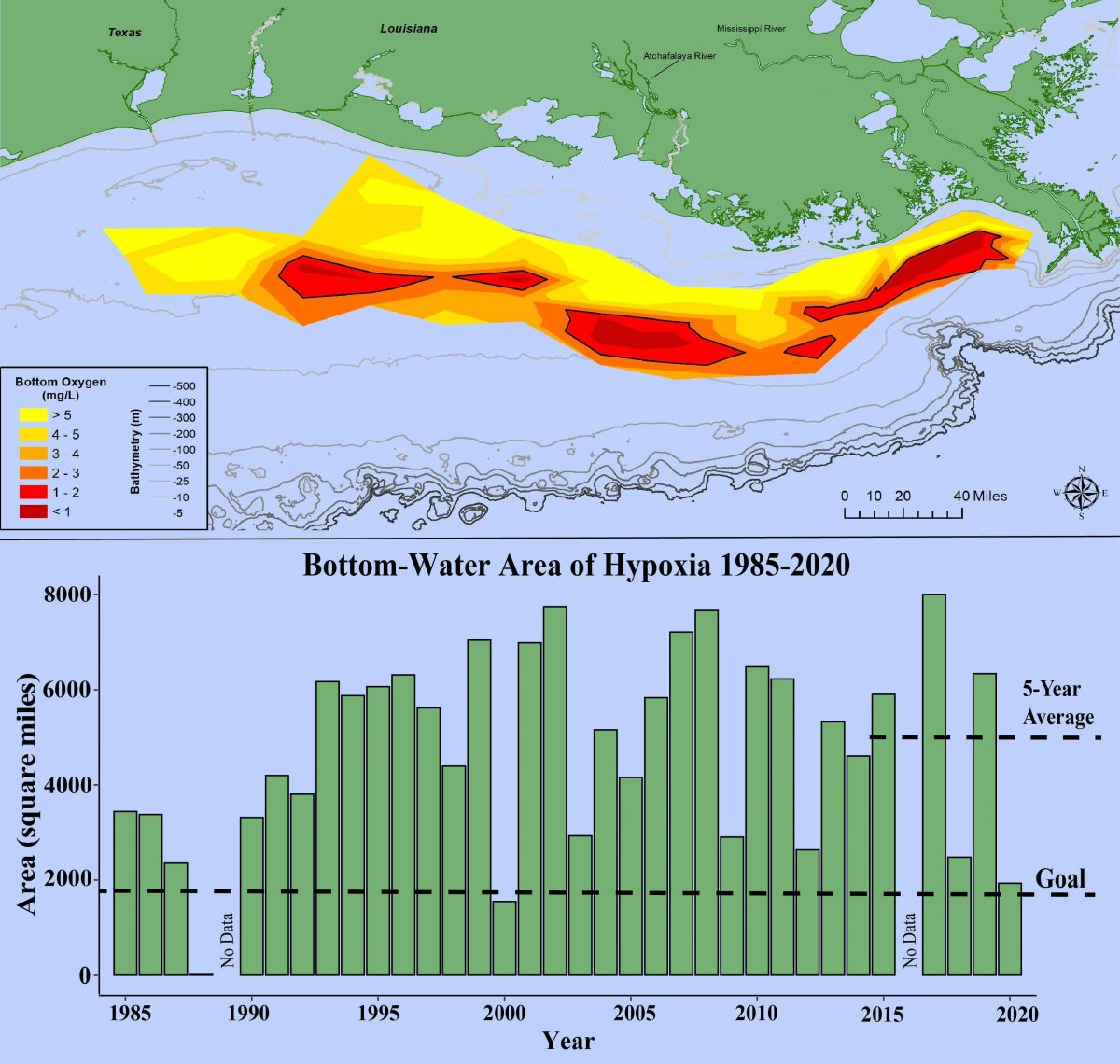

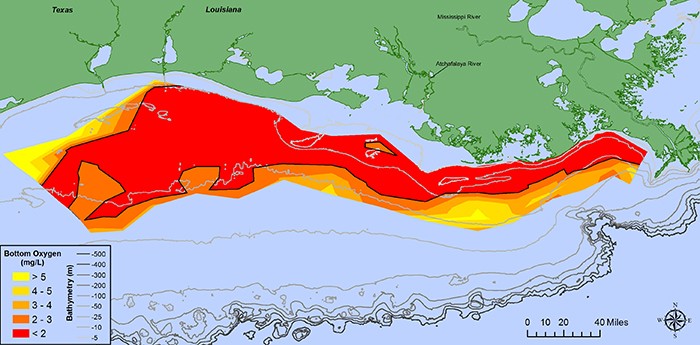

The polluted “dead zone” in the Gulf of Mexico is much larger than scientists predicted earlier this year.

An early prediction put the size of this year’s zone at 4,894 square miles. After an investigation cruise, scientists updated the figure to be much larger, 6,334 square miles.

The four-year average size of this zone is 5,380 square miles. The record size of the zone was 8,776 square miles set in 2017.

The dead zone is primarily caused by excess nutrient pollution from human activities in urban and agricultural areas throughout the Mississippi River watershed. When the excess nutrients reach the Gulf, they stimulate an overgrowth of algae, which eventually die and decompose. This depletes oxygen in the water as they sink to the bottom.

The resulting low oxygen levels near the bottom of the Gulf cannot support most marine life. Fish, shrimp, and crabs often swim out of the area, but animals that are unable to swim or move away are stressed or killed by the low oxygen. This dead zone flows west from the tip of Louisiana and hugs the coast.

Most of the pollution that creates the dead zone arrives there by the Mississippi River watershed, which encompasses 40 percent of the continental U.S. and crosses 22 state boundaries.

That’s how Tennessee contributes to the dead zone, sending mainly agricultural runoff (like fertilizer) and treated human waste down the river. All along Tennessee’s river coast — including Memphis — treated human waste is the biggest source of pollution followed by fertilizer, according to data from the United States Geological Survey.

The federal Mississippi River/Gulf of Mexico Hypoxia Task Force is working to reduce the size of the dead zone to a five-year average size of 1,900 square miles.

“Through state leadership in implementing nutrient reduction strategies, support from [Environmental Protection Agency – EPA] and other federal agencies, and partnerships with basin organizations and research partners, we will continue to tackle the challenge of Gulf hypoxia,” said John Goodin, director of the EPA’s Office of Wetlands, Oceans and Watersheds.

NOAA

NOAA