How can a child drown in a fountain in a public park, in full view of people who could have rescued him? How could a grown woman tumble out the window of a downtown office building? How does a man in a house get killed by an airplane?

Our city’s cemeteries are filled with the graves of men and women, boys and girls, who have died from all manner of causes — accidents, disease, war, even suicide. But there are a few whose deaths are considerably more unusual, even mysterious — deaths that make us stop and ponder their fates, and wonder, “Gosh, what a way to go.”

As Halloween approaches, we thought we’d share their bizarre farewells from this earthly pale with you.

UNDER HEBE’S GAZE

Of all of our city’s parks, downtown’s Court Square probably seems the unlikeliest place for anybody to die by drowning. After all, it’s blocks away from the Mississippi River, and the square’s historic fountain is too shallow to be a danger. Besides, there’s a cast-iron fence around the entire basin.

But when the massive fountain was unveiled back in 1876, topped with the statue of Hebe, that octagonal basin was actually a concrete moat more than six feet deep, often stocked with catfish, turtles, and — if you can believe some accounts — a couple of alligators. And there was no fence around it. If anybody thought the showpiece of Court Square was a hazard, they never said anything about it until the afternoon of August 26, 1884.

That day, 10-year-old Claude Pugh, described as “a newsboy and small for his age,” was sitting on the stone rim of the fountain, playing with a toy boat in the water. He leaned too far over and tumbled in, and since the bottom of the fountain was sloped, and slippery from algae, he couldn’t regain his footing.

What’s incredible is that the park was filled with visitors that day who could have saved the boy, but didn’t. “There were a number of men, women, and children in the square at the time,” reported the Memphis Daily Appeal, “and not an effort was made to save him. Stalwart men did not move a muscle, but stood silently by with staring eyes and gaping mouths.”

After struggling for several minutes, Pugh slipped beneath the surface. Newspaper editors expressed their outrage at the people who witnessed the tragedy: “Their hearts must have been made of stone, and the milk of human kindness in their breasts sour whey. More consideration should have been given a dumb beast.”

When a fireman was finally called to the scene, it took him more than 15 minutes to recover the boy’s body from the water. By that time it was too late. Little Claude Pugh, “the only son of a widow of good family and her chief pride and comfort,” was buried in Elmwood Cemetery. No gravestone marks the site today.

TRAGEDY AT EADS

For 15 years, Benjamin Priddy had been driving a Shelby County school bus, picking up and dropping off students at the little schools in the Eads, Arlington, and Collierville areas. During that time, his driving record had been impeccable.

But on October 10, 1941, Priddy made a fatal error that would result in the worst school tragedy in Shelby County history.

That afternoon, he picked up a busload of kids from the George R. James Elementary School, a little schoolhouse that once stood on Collierville-Arlington Road, just west of Eads. Driving along the two-lane county roads, he had dropped off all but 17 of his young passengers, when he made a sharp turn to cross the railroad tracks that once cut through the heart of the small farming community. Although he had a clear view of the tracks at the crossing, for reasons we will never know he pulled directly into the path of an N.C. & St.L. passenger train roaring toward Memphis at 50 miles per hour.

The tremendous impact almost ripped the bus in half, tumbling the wreckage into nearby woods. Priddy was killed instantly, along with six of his passengers; many of the other children were horribly injured. In those days, few families in the county had telephones. News of the tragedy spread by word of mouth, and frantic parents rushed to the scene, piled the victims into cars and trucks, and rushed them to the nearest hospital in Memphis, more than 20 miles away. “It was one of those sights you never want to see again,” one father told the Memphis Press-Scimitar. At Baptist Hospital, other parents found themselves “in a madly revolving world suddenly but surely spinning off its axis.”

No one aboard the train was injured, and investigators struggled to make sense of the accident. The engineer claimed the bus never slowed as it approached the crossing. Some of the children said they yelled at Priddy to stop when they saw the train hurtling toward them, but he didn’t seem to hear them.

The sheriff told reporters that Priddy had complained of a headache that morning and surmised that “he might have suffered an attack of illness.” Other townspeople conjectured that after driving this same route for 15 years and never encountering a train at Eads, Priddy had probably felt he didn’t need to stop there. On this fateful day, though, the train was running 20 minutes late, and the timing couldn’t have been worse.

Priddy was laid to rest in Bethel Cemetery near Collierville, and the six children were buried here and there in Shelby County. In Eads, the tracks were pulled up years ago, and the only reminder of the accident is a memorial plaque mounted high on a wall inside the town’s community center.

OUT THE WINDOW

The newspapers said Thelma Lloyd was “well-known in the interior decorating field,” and the 41-year-old woman had just returned to Memphis after working for several years with the Marshall Field Company in Chicago. On the morning of December 8, 1941, she left her house at 2258 Monroe, where she lived with her parents, and took the bus downtown to go to work at Seabrook Paint Company. Everyone who saw her that morning reported she was in “good spirits.”

She never arrived at work. After getting off the bus, she walked straight to the Medical Arts Building at 240 Madison and took the elevator to the eighth floor. The elevator operator, who later testified that Lloyd “seemed neither nervous nor excited,” said the woman walked to the restroom at the end of the hall after leaving his elevator. The time was 11:40 a.m.

A few minutes later, downtown workers saw a body plunge from an eighth-floor window of the Medical Arts Building. Nobody could tell whether she had jumped or fallen. Rushing to the scene, they found the woman in the alley below, terribly injured. She was rushed to St. Joseph Hospital, but died within a half hour.

Police were baffled. The woman’s purse was found on the washstand in the bathroom, but there was no suicide note. Although Lloyd’s brother, a former football star for Southwestern, said his sister had recently been ill, she gave no hint that she would take her own life. In those days, before air-conditioning, many office buildings had windows that opened. Police concluded it was possible that Lloyd had rested against the windowsill and then fallen backward out the window.

The Commercial Appeal decided the death was “apparently a suicide,” but the medical examiner was not convinced. On her death certificate, in the space for the cause of death, he typed, “undetermined.” Thelma Lloyd was buried in Forest Hill Cemetery.

LOST AT SEA

Born in Memphis in 1863, Granville Garth grew up in a prosperous home, the son of the president of the Germania Bank here. In his late 20s, he moved to New York to make his fortune, and within a few years, became president of the Merchant’s National Bank in that city.

But then his life took a strange turn. For reasons that were never revealed, in late December 1903, the bank’s board of directors persuaded their president to take a holiday, “to go far from the scenes and incidents distressing him,” as The New York Times put it. So Garth took the steamer Denver to Key West, where he visited for a few hours, then came back aboard when the boat departed for Galveston. When the ship docked in Texas several days later, Garth could not be found. The ship’s crew revealed he had “received cables and messages that seemed to drive him nearer to despair.” Authorities presumed he had jumped overboard somewhere along the way and determined he had done so on Christmas Day.

But why? Family and friends told reporters that the 40-year-old man had “mental anxiety of an altogether personal nature.” At the same time, they said, “What those troubles were are well-known to his friends, and they are known to many in society. Below stairs, in the servants’ world, they are as well-known as to the directors of the bank.”

Nobody could make sense of that. Garth’s brother-in-law later told reporters, “The public does not yet know what the trouble was. Mr. Garth was a disappointed man. He played a game of chess and lost.”

It was all very mysterious. The Garth family put up a stunning granite obelisk in Elmwood Cemetery, inscribed with the cryptic words, “LOST AT SEA.”

DEATH FROM THE SKY

In 1944, Norman Cobb worked as an air traffic controller for Memphis Municipal Airport. The 23-year-old probably never dreamed that he would be killed by an out-of-control airplane that smashed into his house.

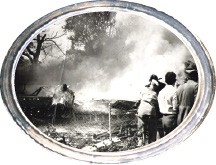

Just before 11 o’clock on April 29, 1944, people in the vicinity of Poplar and Cleveland looked up when they noticed a U.S. Army B-25 bomber in distress. Some witnesses said the twin-engine plane actually flipped over in midair; others said the engines were sputtering or had quit completely. The plane zigzagged for almost a minute, dropped within a hundred feet of Tech High School, then plunged straight down into Cobb’s house at 322 North Claybrook.

The Commercial Appeal conveyed the horror of what happened next: “The brief staccato bark of a dying motor, a plane plummeting earthward, the terrible sound of impact, a dense cloud of black oil-smoke billowing skyward.”

Piloted by a Memphian, Captain Ralph Quale, the B-25 was on a training flight with two other men aboard when the engine failed just minutes after takeoff from the Memphis airport. The scene was utter chaos: “a maelstrom of shouting, running people, of siren-screaming fire apparatus and ambulances, of semi-hysterical women, of grim-faced men who wanted to do something but couldn’t.”

The women had good reason to be “semi-hysterical.” The house on Claybrook was occupied that morning, and everyone in it was killed instantly. Along with Cobb, the victims included his 22-year-old wife, Naomi, their 2-year-old daughter, Garlene, and another resident, 55-year-old Beatrice Withers. Cobb was home that morning because his shift didn’t begin until 4 p.m.

It took the fire department, aided by special chemical units from the airport, hours to quench the flames. No one ever determined the cause of the accident. The pilot never reported a problem with the airplane, and the B-25 had been inspected and overhauled just six days before. An officer with the Army’s Accident Investigation Committee admitted, “I am as much at a loss to explain the cause of the crash as the general public.”

In the days that followed, more than 20,000 people visited the crash site. Although seven lives were lost, everyone breathed a sigh of relief that the doomed airplane had somehow missed Tech High School, the Southern Bowling Lanes, Sears Crosstown, and dozens of other crowded businesses in the area.

Norman Cobb’s death certificate reads: “Accidentally burned to death when Army bomber fell on his home and exploded.” The remains of Cobb and his family were buried in Topeka, Kansas. His home on Claybrook was rebuilt, and there is no trace of the crash site today.

THE MISSING MAN

Just inside the entrance to Elmwood Cemetery is a stunning memorial, almost 20 feet tall, and topped with a lifesize statue of a gentleman named Smith. A stone lion crouches in front of the monument, which is adorned with plaques, columns, and other decorations.

But nobody is actually buried here, because Jasper Smith simply disappeared one evening while walking in downtown Memphis. It’s one of our city’s enduring mysteries.

According to historian Paul Coppock, Smith was a “well-to-do real estate man.” He lived with several sisters and nieces in a nice house on Orleans, near Madison. On the evening of May 29, 1899, Smith left home and told the women he would return before 9 o’clock. He never came back.

Much later that evening, some friends claimed they saw Smith leave a downtown saloon and head down a narrow alley called Whiskey Chute, running between Main and Front, just north of Madison. The next day, police found his horse and buggy several miles away, at Poplar and Belvedere, but no one ever saw Smith alive again.

Coppock writes, “Gradually, the town accepted a theory that thugs, who assumed he carried large amounts of cash, had jumped him in the dark and dumped his body in the river.” But there were other theories, among them a report that he had withdrawn $1,000 from his bank that morning and had planned his disappearance because “the women he was sharing a home with were driving him crazy.” But if you were going to leave town, wouldn’t you take all of your money with you? And rumors persisted that his family had killed him for their inheritance.

The newspapers held out hope for his return, with one story saying that Smith had probably decided to visit some of his real estate holdings in the area, though the reporter didn’t explain why he would do that at night and leave his horse and buggy behind. Even so, the article said that Smith “is expected to reappear in due season and in good shape.”

He didn’t. Years later, he was declared legally dead, and his sisters erected the monument in Elmwood. The rest of his family eventually was buried nearby, their graves marked by almost identical memorials.

A BOLT FROM THE BLUE

On the afternoon of June 6, 1913, several children were playing in the front yard of a home at 1674 Lawrence Place in Midtown. Without warning, a black thunderstorm swept through the city, and the children dashed for cover from the fierce wind and pelting rain. Six-year-old Aileen Embury scampered across the street to her own home at 1677 Lawrence Place.

She didn’t make it.

The Memphis Daily Appeal reported, “As she ran toward her home, a blinding flash of lightning appeared around her and the girl sank to the ground. Persons who rushed to her found her dead. The bolt that caused her death flashed directly to the child’s body. When it had gone, a life was the toll of damage done. No mark was left on shrubbery or houses nearby.”

The funeral service, as was the custom of the times, was held at Aileen’s home the next day. She was buried in Forest Hill Cemetery.