You’re pumping up Memphis at an out-of-town cookout. Sun Studios and Stax? Check. Barbecue? Check. Humble-brag on Memphis water? Check. Now it’s time to turn up the heat and break out that bit sure to set the HGTV crowd salivating — affordable housing.

“You can get a lot of house for a lot less in Memphis,” you say. “It’s well-built stuff, too. Old craftsmans, bungalows, and cottages from the early 1900s. And I can walk to bars and bike to work.”

They ooh and aah appropriately (but you know deep down they’re thinking, “Well, at least I don’t have to worry about crime in my neighborhood.” And you’re all, like, oh my god, dudes, give it a rest).

Memphis ends up on lots of lists. Still, our rankings don’t make the news like they used to. Remember how we were always among the dumbest, fattest, and sweatiest people in America, according to clownfart.com (or whatever)?

But there was one list we’ve always liked. For as many years as I can recall, Memphis has always ranked high in Kiplinger’s list of “most affordable cities.” We may not have downtown Nashville’s rolling hot tubs (not yet, lord help us), but you sure can get some major housing bang for your buck here.

Here’s what Kiplinger’s had to say about the Memphis housing market this year, in which we ranked 4th for affordability across the country (up from 7th in 2018): “To say that real estate is cheap in Memphis is an understatement,” reads the story. “You can buy a home for less than $100,000, an amount that barely qualifies as a down payment in many of the most expensive U.S. cities you could live in.”

But there’s a rub. The needle moved up on the median home price between 2018 and 2019. If you stacked all the houses in Memphis from highest cost to lowest cost and picked one from the middle, that house has become $10,500 more expensive in the past year, according to Kiplinger’s.

Is it a dark omen of things to come? Are we about to “It City” our way into some Nashville-style, crazy-expensive dystopia? Not likely, say the experts I talked to.

But business is booming here, if you haven’t noticed. No, construction cranes don’t litter our skyline like they do in Nashville. Our boom is different, more conservative, more Memphis, really. For one, we have plenty of empty houses and vacant land on which to boom, say those experts. Though, one Midtown real estate veteran I spoke with said supply is tight and it’s pushing up home values.

But Memphis does follow one national trend. More people (especially younger people) are choosing to live in the inner city. They want to walk to restaurants, bike to work, and live among the old buildings that give a city its identity.

And, of course, developers are eager to give these young customers a place to go. Consider South End — once a spooky, deserted warehouse district below South Main. The area now pulses with the thousands of residents who live, maybe work, but definitely play right around Tennessee, Georgia, or Carolina streets. They reside mostly in brand-new, fresh-looking apartment complexes like the ones at South Junction. Built by Henry Turley Co., the project is described as “part historic Downtown Memphis, part modern community.”

But some see the South Junction apartments and those around them as bland, cookie-cutter designs that belong in the suburbs, not historic Downtown Memphis. Aesthetics and historical alignment have been a source of controversy as developers continue to build modern-looking developments among the city’s more historic neighborhoods, such as Central Gardens and Cooper-Young.

Call these all growing pains, if you like. The “Urban Renaissance” has been happening in cities all over the country for years, and most of them are experiencing similar pains.

Photographs by Justin Fox Burks

Photographs by Justin Fox Burks

More people are choosing to live in the inner city, sending development back Downtown.

LIKE IT’S HOT?

Okay, the housing market in Memphis is hot. We’ve all probably heard that by now. So, like, how hot are we talking here?

Since 2014, investors have poured about $14.7 billion into 290 Memphis projects, according to data from Cushman & Wakefield Commercial Advisors, a local commercial real estate firm. These projects are industrial or commercial facilities, hotels, schools, parks, multifamily homes, and more — the engines of an economy.

Here’s the hotness: 29 of those projects are complete ($520 million), 107 are under construction ($6 billion), and 158 are proposed ($8 billion). So, most of these projects aren’t even started yet. Big-money investors, it seems, believe in the future of Memphis. Which is undeniably hot.

That $14.7 billion figure does not include individual home builds (though it does include big, multi-unit projects such as The Citizen at McLean and Union). According to Chandler Reports, 639 single-home building permits were pulled in Shelby County last year.

The number of homes sold was flat from 2017 to 2018, rising slightly from 18,871 to 18,957 sold, a .5 percent increase, year over year. But the average home price rose 4.4 percent across Shelby County — from $165,755 to $173,078. The price of that median home — the one plucked straight from the middle of the most- and least-expensive homes here — rose slightly (2.7 percent) from $130,000 to $133,540, according to Chandler.

Tony Pellicciotti, a principal at local architecture firm Looney Ricks Kiss, puts it a bit more simply: “Memphis has turned the corner from being a market that was critical [of itself] and down on itself for so long to being one that actually has optimism and is thriving.”

Though Memphis rents may be on the rise, they’re still a bargain compared to other cities of comparable size.

Where Are the People?

On Memphis Facebook, there is often a common thread: “We’re building all this stuff — these apartment buildings and high-rises. Who is going to live in them?” It’s a fair question.

About 100 people moved into Austin, Texas, every day in 2018. About 83 were moving to Nashville each day that same year, according to the most recent count. Both figures were down slightly from 2016 and 2017.

From 2010 to 2018, the U.S. Census Bureau says about 3,729 people moved to Memphis (from 646,889 to 650,618). That’s about 466 people per year — around two-thirds of a person per day.

“Slow and steady” is how one consultant put the city’s household growth in 2017. Back then, the city hired Robert Charles Lesser & Co. for a snapshot of our market and some suggestions on how to build on our strengths. That study said we could expect about 1,300 new households here each year (assuming no major economic events) from now until 2040.

Josh Whitehead, planning director of the Memphis and Shelby County Office of Planning and Development (OPD), says that while our growth rate “may look pretty good” to a Rust Belt city, Memphis is one of the slower-growing Southern cities. There are reasons for that, he says, and he didn’t mention crime even once. Chief among his reasons — isolation.

“For being on the east side of the Mississippi River, we’re probably further from another big city than any other [similar] metropolis,” Whitehead says. “You look at Atlanta and its synergy with Chattanooga now. Cities all up and down the Eastern Seaboard [have this synergy], and like in North Carolina with the Research Triangle.”

Asked who will fill all these new Memphis residences being built, Whitehead says it could be those who would have chosen to live in a subdivision in unincorporated Shelby County. Since those are drying up (thanks to city officials cutting new sewer taps to them), those people have to choose between living in a municipality (with amenities like sewer and trash pickup) or going it alone in rural Eads or elsewhere. Once they weigh city taxes against conveniences and transportation costs, many may choose to live in town, he says. Especially younger people.

Downtown’s narrative very much tracks that ongoing national story of young people seeking “authenticity.” Jennifer Oswalt, president and CEO of the Downtown Memphis Commission (DMC), says the area also gets a fair number of retirees or empty-nesters looking to downsize. But she’s seen an interesting trend among those just beginning their careers.

“A lot of people are making choices independent of their jobs,” Oswalt says. “It used to be the case that you wanted to be near where you worked. But now people are choosing where they want to live — even if it’s choosing a city — before they find a job. They may say, ‘I want to live in Memphis,’ come here, and then find a job.”

Those moving Downtown are, largely, coming there from other parts of Memphis. Oswalt said that’s the case for about 70 percent of those moving there. About 20 percent are moving from outside the Memphis region, and the other 10 percent are from outside Shelby County.

But Whitehead notes that the city does have a wider draw. Fortune 500 companies like FedEx, AutoZone, and International Paper call Memphis home. There are also huge medical device companies like Medtronic, Smith & Nephew, and Wright Medical here. And St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital draws employees from all over the world.

Debbie Sowell, a veteran Midtown real estate agent with InCity Realty, says the draw for many of the new apartment complexes like The Citizen and Madison@McLean could be from the Downtown area’s medical education institutions — the Southern College of Optometry (SCO) and the University of Tennessee Health Science Center (UTHSC).

“We have a lot of med students with SCO and UTHSC, and they tend to have money,” Sowell says. “They’re going to rent these nice places with low maintenance. They’re going to be here for two to four years, and they’re going to sleep and study and not have much of a social life. The people who are living and enjoying Midtown, they want something a bit more roomy.”

Are We Still Affordable?

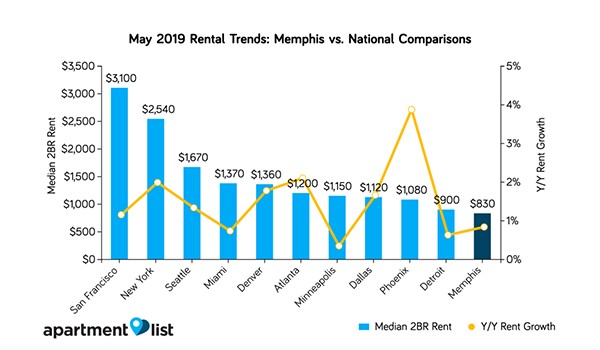

An email hit my inbox recently with a warning, bolded in capital letters: “RENTS ON THE RISE.” After two months of rent declines in Memphis, the email warned that the rental rate went up from April to May. Oh, no! Well, not so much. It turns out that rent rose by 0.3 percent, month-over-month, and it rose 0.8 percent from 2018 to 2019. That yearly growth rate in Memphis “lags the state average of 1.6 percent, as well as the national average of 1.5 percent,” according to Apartment List, which concluded: “Currently, median rents in Memphis stand at $700 for a one-bedroom apartment and $830 for a two-bedroom.”

In Tennessee, Franklin, at $1,310 per month, has the highest rent rate for a two-bedroom apartment. Around the country, Memphis rental rates are still a bargain. San Francisco ($3,100 per month) is the highest.

At The Citizen, rental rates for a two-bedroom apartment are listed between $2,100 and $2,300 per month, according to its website. Two-bedroom apartments at The Chisca Downtown run from $1,350 to $1,800. At South Line (the new apartments at Central Station), two-bedroom units start at $1,640 per month.

Sowell says she worried about her Midtown rental units when new apartment buildings began to spring up all over Memphis.

“Then I thought of it on the flip side — there are some junky rental apartment buildings in Midtown that, for the owners, have just been cash cows,” Sowell says. “They’ve been making money, but they haven’t really made any improvements.”

She said she hopes the influx of shiny, new rental options will make landlords up their games as they realize they might have to improve their properties to compete.

Oswalt says affordability has been maintained in Downtown, at least with any project the DMC incentivizes. That program requires that 20 percent of the units in a building that gets DMC tax breaks be set aside for those making 80 percent of the area median income, a figure set by the federal government.

Oswalt adds that more affordable housing is on the way for Downtown, pointing to projects such as 2nd Street Flats, being built by Elmington Capital, which specializes in more-affordable housing. Oswalt says new, affordable housing will also open soon in South City.

“We really do feel good about the number of affordable units coming along,” Oswalt says. “We continue to encourage that in any large development, we make sure they are growing both ends of spectrum. Our market study really does show that there’s an almost unlimited demand for affordable housing Downtown.”

Whitehead says Memphis has so many opportunities for infill development (building on vacant land or renovating existing buildings) in so many neighborhoods, “that I don’t foresee, in the future … our ranking as the most affordable city in America ever significantly changing.”

“Is Midtown as affordable as it used to be?” Whitehead asks. “Part of me says you can still find apartments like I used to live in for less than $1 per foot. Are there as many? Maybe not.”

But, he says, many people are choosing the newer Midtown units, since they have more modern conveniences.

Hey, where’s the porch in this place?

Fighting the Past and the Future

Take a drive around East Nashville. Tall, modern houses — seemingly hundreds of them — nestle among Cape Cods, craftsman bungalows, and mid-century ranches. It’s like an alien invasion, or Dwell magazine gone country.

It’s not yet the same in Memphis, but the new houses are here, popping up all around Midtown — not on the same scale as Nashville, but when you see them, the difference is jarring, like finding a Kenny G record at Goner.

“We want a seamless transition, where you don’t turn the corner and go, ‘How in the hell did that get there?'” says Gordon Alexander, a longtime Midtown activist and president of the Midtown Action Coalition. “We just want something that looks pretty much like the neighborhood and blends in with everything else. Some of these things are hideous; that’s the only way to describe them.”

Memphis prides itself on its authenticity. Consider the Earnestine & Hazel’s slogan “ragged but right.” Some, like Alexander, fear that the new designs are an erosion of that authenticity, the slippery slope to Memphis becoming some bland, McDonald’s-land or (even worse) Nashville.

Those new designs are a sign of Memphis’ growing pains — pains that have brought new money and new residents to town, but have also brought hours of angry comments at land-use and design boards meetings at Memphis City Hall.

Many of the new designs come from developers looking to attract customers who want modern amenities, and who, just maybe, aren’t looking for that old-school, Midtown charm — or don’t care about it.

Whitehead says much of the ire drawn by these new buildings comes from a single point — the garage faces the street. This type of new home construction was allowed because of the way Whitehead interpreted city code. As he read the code, garages could face city streets if they were set eight to 10 feet further from the street than the front door. Examples of this are numerous tall, new houses on Bruce, Blythe, and Carr in Midtown, each with a tiny covered porch leading to a front door next to a large garage door.

Why is this a problem? Aesthetics, yes, but also porches. Memphis’ front porches are places to sit and be seen by your neighbors, places to say hi, to chat, to get to know your neighbors, and thus build a stronger community bond. Whitehead says he’s heard the complaints and is making a change.

Whitehead says his new deputy administrator Brett Ragsdale has dug into city code and the Unified Development Code (UDC), which was written by out-of-state consultants. Ragsdale found a section of code — totally separated from the UDC, Whitehead says — that prohibits garages facing streets unless that is the predominant style on the block.

Whitehead says it’s taken nine years for his office to put together all the disparate sections of the Memphis zoning laws and code enforcement, and it is addressing that issue right now. His office is also tearing down a wall between the divisions that make zoning rules and those that review and enforce those rules, Whitehead says. All of this will refine the boundaries of future construction and align messages about it coming from city hall.

The Citizen at McLean and Union

Can It Last?

That’s hard to say. Pellicciotti says the Memphis development community is “extremely conservative.” They’ve been watching as an influx of capital is pouring into town from around the country and world. The outside investors bring new ideas about the Memphis market — and the potential for a lot of fast growth, he says. “It’s something that everyone in the development community is monitoring and hoping to enjoy the growth curve, but also being cautious about how mature it is.”

Sowell says she’s watched the strong housing market soften a bit. “There’s a lot [of housing] that started at $330,000 or $315,000, but it needed a bit of work,” she says. “The agent probably thought they could get it, with the market just skyrocketing, but it wasn’t until it came down to under $300,000 that it sold. So, I think the expectation that I can get top dollar for my house even though it needs work is not as strong as it was about a year ago.”

CNBC rang an alarm last month as it tweeted, “Thinking of buying a house? Read this first: These 40 cities may be on the brink of a housing crash.” CNBC said a firm called GOBankingRates “evaluated cities based on multiple criteria: percentage of homes with mortgages in negative equity, foreclosure rates, delinquency rates on mortgage payments, homeowner vacancy rates, and rental vacancy rates” and ranked them. Yep, Memphis was one of those cities (ranked 35th).

There’s some comfort in the knowledge that cities across the country are growing, just like Memphis. And just like Memphis, they have the same growing pains and the same worries about the future.

“It is some respite to know that we are no better or worse off than anybody else,” Whitehead says. “Although, because of our relatively slow growth, I bet we don’t have as many pains as some other cities. I mean, just look at Nashville.”