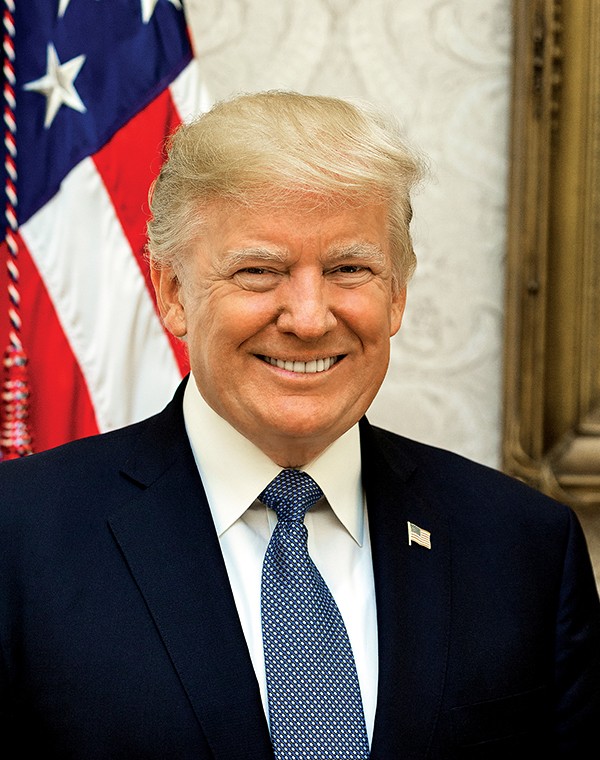

From the very beginning, it was obvious that calling the 2020 presidential election would take a while. Joe Biden was doing well enough in the nation’s suburbs to raise Democratic hopes, but Donald Trump’s re-election campaign was performing tenaciously enough to suggest that his 2016 victory was more than a fluke. Both parties were gaining in areas where they trailed four years ago, and leads were being swapped back and forth in several key states.

Democrats seemed likely to prevail in some key Senate races, though it was uncertain whether they could close the gap with the GOP in the upper chamber.

The outlook was complicated by the fact that the president is certain to follow through on his frequently voiced threats to litigate in areas where the outcome of the vote did not turn out to his satisfaction. All in all, the main thing demonstrated by the unprecedented outpouring of votes from both halves of the American electorate was that the United States of America remains profoundly disunited.

REUTERS | Mike Segar

REUTERS | Mike Segar

(left) Donald J. Trump and (right) Joe Biden

Never before in an American national election had questions of turnout loomed so large. Both sides strained to get every one of their identifiable supporters to the polls, and not a day had gone by without President Donald Trump or his surrogates expressing over-hyped concerns about the prospect of unprecedented numbers of voters — especially via the medium of mail-in ballots, a mode of voting that was liberalized in virtually every state as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

There had been big-time anxiety on both sides of the mail-in issue, as on the election results themselves. On the one hand were Trump’s daily accusations, totally without evidence, of inevitable ballot fraud and his stated refusal — as in 2016 — to accept the possibility of an unfavorable verdict by the voters; on the other hand were the fears of the Democratic opposition that Trump would stop at nothing to obstruct such a verdict. The new director of the U.S. Postal Service, a billionaire Trump donor with the Dickensian name of DeJoy, seemed determined to do his bit by decimating pre-election postal services, reducing employee overtime, uprooting mailboxes, and destroying mail-sorting machines.

Closer to home, Tennessee state government, overwhelmingly dominated by the president’s GOP party, hunkered down in an attempted last-ditch defiance of judicial mandates that had relaxed the state’s restrictions on absentee voting. Tre Hargett, Tennessee’s secretary of state, insisted to a congressional investigating committee that state law did not countenance fear of COVID-19 as a reason to vote absentee. “Pitiful,” responded Senator Angus King of Maine, an Independent. And reflecting both concern about the intractable virus and, as polls would indicate, a zeal for change, the applicants for mail-in ballots multiplied everywhere, as, for that matter, did the number of early voters.

WhiteHouse.gov

WhiteHouse.gov

Donald J. Trump

So, for better or for worse, did the crowds that continued to flock to the site of mass rallies conducted by the barnstorming Donald Trump: For better, in that the president continued to be the source of legitimate mass enthusiasm on the part of his sizable hard-core base and thereby reinforced the importance of populist energies; for worse, in the sense that each one of Trump’s showy and largely maskless assemblies threatened to be a super-spreader event to the detriment of the general health and welfare.

Among the other rolls of escalating numbers was the one that could only be called a national casualty list: On election eve, the number of COVID-19 cases in the United States had risen past 9 million, the number of deaths was more than 230,000 at a national rate of nearly 1,000 new fatalities a day, and there was as yet no light at the end of this tunnel. The president himself, of course, had come down with the ailment; so had First Lady Melania Trump and numerous other denizens of the White House, including several members of the staff of the president and of Vice President Mike Pence.

With first-rate state-of-the-art medical facilities at their immediate disposal to facilitate recovery, they were still the lucky ones. For the rank and file of Americans, the outlook was more ominous. The Trump administration largely eschewed a national anti-virus policy, leaving it to the individual states to devise strategies of their own insofar as they had means or inclination to do so. Bizarrely and tragically, attitudes toward the coronavirus pandemic began to bifurcate according to the nation’s political divisions, with “red” or Republican states largely following the president’s exhortations to open things up — business, schools, whatever — and “blue” Democratic states attempting in various measures to keep the clamps on overtly public activity.

For all practical purposes, the nation resembled (and still does) an isolation ward. No plays, movies, or other dramatic entertainments save those that were streamed online; meetings, too, conducted via computer; workforces operating from home; athletic events taking place without their audiences and in locations other than the cities that teams supposedly represented. Everything was down the rabbit hole or through the looking glass.

Suddenly that non-word inadvertently coined by Warren G. Harding in the presidential campaign of 1920 has come into its own: “normalcy.” Harding was speaking in the context of a just-concluded world war of then-unprecedented savagery and, not incidentally, of a marauding virus, the Spanish influenza bug of 1917-18 that killed an estimated 100 million people worldwide.

REUTERS | Brian Snyder

REUTERS | Brian Snyder

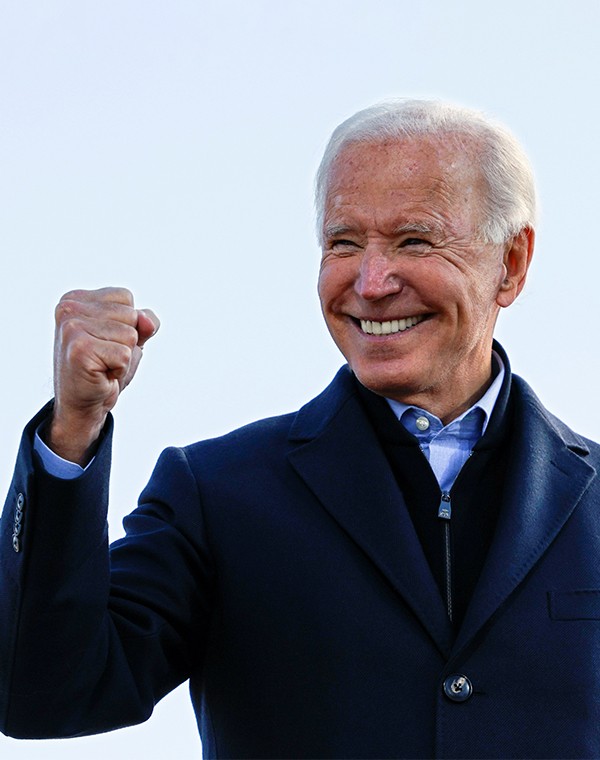

Joe Biden

If there is any quality that Democratic nominee Joe Biden demonstrated during his run for the presidency, it was that of being normal — not dull-normal, as Trump’s preternaturally stolid vice president, Mike Pence, often seemed to be, but normal in the sense of having recognizable neighborly qualities. Biden lacks Trump’s capacity for theater, as he also lacks the charismatic personality of his former governmental partner, Barack Obama. But his ability to be convincing with a vernacular (or normal) phrase like “C’mon, man!” is unparalleled.

During the Democratic presidential primaries of the winter and spring, most of the score or so of Democratic presidential aspirants declared themselves on the cutting-edge side of public issues. Biden was singular in his hewing to the center. It held him back in every primary contest but the deciding one, South Carolina, when the race had narrowed down from the field at large to one of Biden versus the party progressives’ main man, Bernie Sanders.

In that context, it was both ironic and appropriate that Biden’s eventual choice of a running mate came down to Kamala Harris, the liberal California senator who had chided him in an early debate for being too willing to work across the aisle with the other side.

There was a time, back in the summer, when domestic disturbances arising from the killing of George Floyd by police in Minneapolis and the ever-simmering fact of racial inequities seemed to give an electoral opportunity to Trump and the advocates of the social status quo. And there was arguable hypocrisy on the part of those participating in the demonstrations or defending them while turning a blind eye to the violence and potential super-spreader aspects of them. But if polls are correct, the specter of looters has proved as irrelevant to the case of Joe Biden as has the imputation to him of socialism.

Still, there was no denying that an air of crisis accrued to the presidential election of 2020. Conservatives did sense the onset of long-pending social and demographic changes that frighten them. Liberals did abhor the continued power and influence of a monolithic monied economic class and its attendant rampant income inequality. And Americans at large could not fail but take alarm at such existential threats as the nonstop environmental disasters — fires, hurricanes, floods — that have afflicted the country’s coasts and its heartland alike. Trump may be the most important skeptic in public life regarding the reality of climate reform.

And so it went, up until Election Day. Pulses racing in anticipation, hearts pounding in dread. This was not like the World Series or the Super Bowl. There is no “life goes on” sense in case of a loss. It was not even like the nomination (and subsequent rushed Senate confirmation) of the conservative Amy Coney Barrett, a Rhodes College graduate, to the Supreme Court. For all the fear and trembling Democrats endured over that, some pundits were divining in it — the possibility of post-election judicial interventions notwithstanding — a silver lining: The more-than-likely nullification of the Affordable Care Act (Obamacare) would create both the opportunity and the incentive for a Biden administration to consider Medicare for All, and what the Court might take away from Roe v. Wade, either the states or Washington itself would presumably have a chance to restore — or improve. A Democratic Congress and Senate would surely attempt to legislate a return to the status ante quo. Meanwhile, looking forward, there might be more Democratic votes in the heartland for voters estranged from the party for a generation on social grounds.

But Trump has been Trump for four years. Millions of Americans, and not only progressives, counted it as a miracle that the country’s social fabric had held together at all during this era of persistent turmoil and raging divisiveness, amid a tweet-driven cult-of-personality presidency that seemed more like a TV reality show gone amok than a process of government. None of this is to gainsay what many, and not only Republicans, will acknowledge to have been the country’s pre-pandemic economic successes — though the long tough slough back from the fiscal crash of 2007-08 was begun during the presidency of Barack Obama, Trump’s Democratic predecessor.

And Trump’s stock-market numbers, boosted by his huge corporate tax cut in late 2017, arguably signified a widening wealth gap between haves and have-nots at least as much as it did a sense of general prosperity. Whatever the case, Trump could, and did, trumpet a win in the declining numbers of Black and Hispanic unemployment, as he also did (through draconian means) a measurable decrease in both legal and illegal immigration into the country. He could not, however, keep out another more powerful immigrant, a strain of highly contagious coronavirus that came to be known as COVID-19.

History may ultimately judge the Trump administration to have been snake-bit, though the bad luck (or karma) implied by that term may have been the natural consequence of the president’s penchant for snake-handling — i.e., his eccentric or risky or downright dangerous deviations from the hitherto accepted (here’s that concept again) norms of American government. All things considered, his four years to date seem in retrospect to have been favored by the indulgence of the gods.

As significant as the presidential race has been, the consequences of the 2020 election transcend what will have happened in it. The reality is that, even as you read this and possibly for weeks afterward, we may not know for sure what direction American government will be taking henceforth. There were 11 or so Senate races that, going into the election, were regarded as being competitive. Given the near certainty that litigation of the election results will occur, it will be difficult for a time to assay the prospects for legislation or to tell who actually is in charge, or to what extent.

And, no matter who commands the technical majority, there is likely to remain some vestige of the impasse between parties that has in recent years turned self-government into something like a Cold War of the civil variety. Though it caused him some grief, initially, as he began his primary run, Biden’s belief in reconciliation as an aim in itself would become a major selling point to the nation at large and especially to independents and Never-Trumper crossovers from the Republicans. And, though Trump had offered little but scorn to the leaders of the political opposition, his very demagogic success in appealing to working-class remnants of a onetime Democratic consensus had suggested something of a pathway across the divide.

In a true sense, factionalism — or as it is now being called, tribalism — may have run its course. As had been the case at other turning points in the nation’s history, the twain would have to meet — or else.