Science fiction claims to be about tomorrow, but it’s really about today. Predicting the future requires seeing the present clearly; if the artist gets it right, their vision will last. That’s the secret of the success of Frank Herbert’s 1965 novel Dune. It’s set about 8,000 years in the future, but underneath all the sandworms and psychic messiahs, the human dynamics still feel spot on. Competing interest groups recognize a chokepoint in society, and battle to control it. The decidedly Arabic intonations of the Fremen, the indigenous population of the desert planet of Arrakis, is no accident. Eight years after Dune’s publication, the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries, instituted an oil embargo, which severely disrupted the economies of the West, destabilized the colonial world order the great powers had been building for 400 years, and set the stage for the conflicts that have dominated the 21st century.

In Dune, the equivalent of oil is spice, a psychedelic drug that enhances the psychic abilities of its users (it was the ’60s, after all), allowing specially trained addicts to navigate faster-than-light spaceships, thus enabling the development of a sprawling interstellar empire. Spice can be found on only one planet in the Imperium, so Arrakis (aka Dune) becomes the focus of great-power politics, war, betrayal, and rebellion.

The political complexity of the text is only one reason why it has long been considered unfilmable. Long passages take place entirely within the minds of the characters. The galaxy lacks intelligent computers or cute robots, because of an ancient jihad. There’s a thousand-year eugenic breeding program by the Bene Gesserit, a cabal of space witches, to produce the Kwisatz Haderach, a psychic super-being who will access the genetic memories of the entire human race and impose “benevolent” rule on the galaxy. That’s a lot to explain to a 10-year-old squirming in a theater seat.

Not that filmmakers haven’t tried. Watch the documentary Jodorowsky’s Dune for the story of the first attempt. In 1984, David Lynch got a crack at it, and failed spectacularly — the best way to fail. In 2000, the SyFy Network produced the most successful Dune screen adaptation by spreading out the sprawling story into a miniseries. Now, it’s Denis Villeneuve’s turn in the barrel.

Going in, Villeneuve looked like the best person for the job. Arrival is one of the best science fiction films of the 21st century, and Blade Runner 2049 is a mesmerizing, minor classic. To do Dune right requires a big bet and patient hands. At $165 million, this pandemic-delayed epic is much cheaper than the average Pirates of the Caribbean installment.

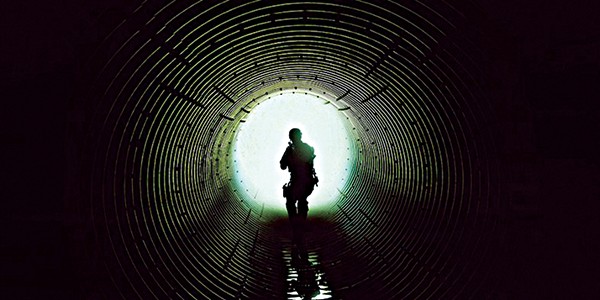

Unlike Disney’s Depp-driven wank-fests, every cent is on the screen. This Dune is one of the most beautiful sci-fi films ever made. Villeneuve looks to Lawrence of Arabia for inspiration (David Lean turned down Dune in 1971), and riffs on other cinematic fence-swings like Apocalypse Now and Eisenstein’s Odessa Steps. The production design, from mountain-sized spaceships to the dragonfly-like ornithopters, is immaculate.

None of the actors are just collecting paychecks. Timothée Chalamet plays Paul Atreides, the deeply conflicted revolutionary leader, as the callow youth of Herbert’s novel. He’s mostly along for the ride as galactic events unfold around him, until he embraces the bloody destiny he knows he can’t escape. Rebecca Ferguson gets the juiciest role as Lady Jessica, the concubine who forces the hand of the Bene Gesserit out of love for Duke Leto (a pitch-perfect Oscar Isaacson.) Josh Brolin and Jason Momoa play Paul’s military mentors, while Javier Bardem comes in late as Stilgar, the Fremen leader who will join Muad’Dib’s jihad. Zendaya is Chani, Paul’s future Fremen consort. She features prominently in Dune’s advertising, and will play a vital part in the story’s future, but for now she’s mostly relegated to swishing around like a Ridley Scott perfume ad.

Dune is an epic 156 minutes long, but only covers about the first half of the first book. That’s a lot of table-setting, but the story’s complexity needs room to breathe — especially since Villeneuve tells it without the dozen layers of voiceover Lynch required. It’s engrossing enough to sustain attention, except for one thing: Hans Zimmer’s score is awful. I like ambient music as well as the next guy, but Zimmer’s whoopee cushion subwoofer schtick gets old quick. The story would have been better served by a traditional symphonic score — or even the prog rock Toto made for Lynch — to shape the emotional peaks and valleys.

Music aside, the spectacle is unparalleled, and Herbert’s story still resonates. Two of Villeneuve’s images swirl in my mind: Duke Leto striding down a spaceship ramp to the tune of space bagpipes, confidently leading his family — and the empire — to ruin in the desert; and Paul’s recurring vision of his future, where piles of burning bodies stretch to the horizon. Dune is a different kind of blockbuster, a rare feat of cinematic virtuosity.