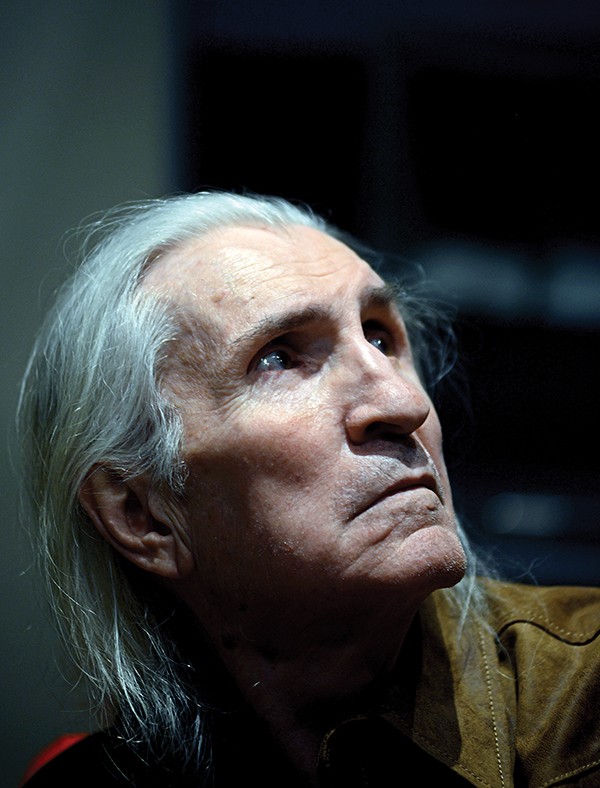

December 2024 note: In light of Stanley Booth’s death this past week, we thought Flyer readers might enjoy Jackson Baker’s profile from a few years back.

“I think it’s only fair that all those people are dead, and we’re not.”

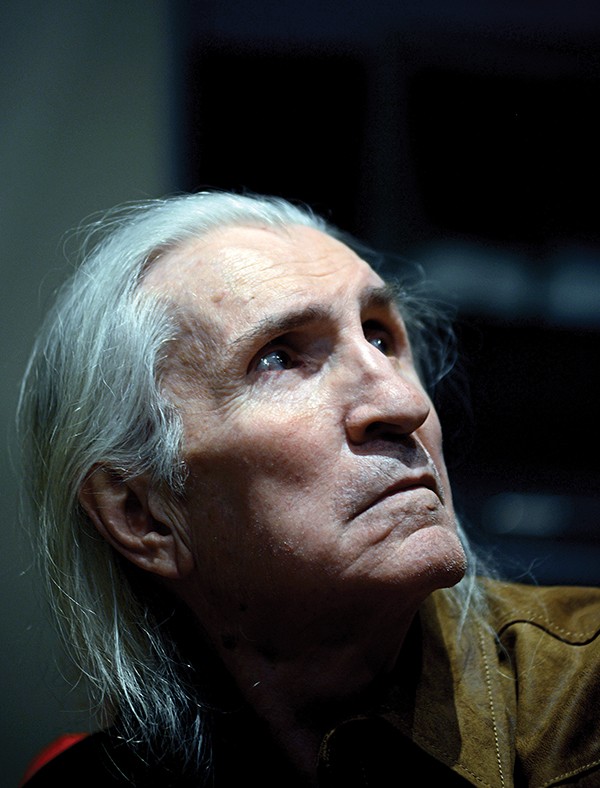

This was said on a recent evening by Stanley Booth, aged 76, and my friend for well more than half a century. Yes, we have outlived our share of contemporaries, but I am not quite sure how to take the remark, especially since Stanley promptly begins listing exceptions to this category of the justly deceased.

Among them are such other longtime Booth friends as Irvin Salky and Charles Elmore (the latter known as “Charlie Brown” for his roundheaded resemblance to the Peanuts comic strip character), both gentle souls, both legendary facilitators in these parts of general folk-art awareness, and both, as it happens, in on the creation of the early Memphis blues festivals. Salky died from complications of a stroke in 2016; Elmore more recently from the ravages of a beating and maiming by street toughs.

Another death to be lamented was that of Jim Dickinson, the one-man music renaissance whose legacy lives on in his two sons, Luther and Cody, both players in the North Mississippi Allstars; in the Dickinson-founded group Mud Boy and the Neutrons; and in other hell-raisers both local and in the musical mainstream at large. It has been all of nine years since Dickinson’s passing, and Booth, then living in his native state of Georgia, recalls his surprise and dismay in learning of it:

“I didn’t know Dickinson was that ill. You just don’t expect your friends to die like that.” Booth remembers having a long-distance phone conversation with Dickinson three days before his death, one that Dickinson closed out by saying, “Look, we could talk like this for hours, and we will.”

Booth is the author of celebrated literary works like The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones, a lengthy, sui generis chronicle of the great rock-and-roll group; and of Keith, an in-depth portrait of Stones guitarist Keith Richards; and the purposely misspelled Rythm Oil, a collection of profiles and other pieces about the music of Memphis and the rest of the American South.

Booth is now readying for publication another collection of 26 pieces, to be entitled Red Hot and Blue, which might be recognized as the name of the late-night radio show presided over in the ’50s by the late redneck DJ Dewey Phillips, who first broadcast music by Elvis Presley and who, as much as anybody else, deserves credit for bringing rhythm and blues into the musical mainstream.

Booth’s recollection of Phillips, the culminating piece in the new collection, will doubtless go far toward reminding the world of Daddy-O Dewey’s contributions, and the new book as a whole may do the same for Booth himself.

To talk with Stanley Booth is, at times, to encounter an unusual sense of fatalism. Or perhaps, rather, a heightened sense of the vulnerability and impermanence of the human flame. He mused recently that he befriended Phillips in the year or so before the death of the iconic DJ — then hanging on to life and credibility at a small radio station in Millington — and that, similarly, he had met Stones co-founder Brian Jones before Jones’ death by drowning in a swimming pool, and that he had been in a room at Stax-Volt studio with Otis Redding when the great Memphis soul artist was composing “Dock of the Bay,” the classic ballad he recorded just before his touring plane went down in 1967. Booth sums it up by saying wryly, “Meet Stanley and die.”

As recently as August 2012, Booth received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Smithsonian Institute, but that and a slew of like honors did not prevent him from tottering on the edge of an existential abyss.

In August of 2012, his third marriage, to the poet Diann Blakely, was in tatters, and her death proved unsettling in numerous ways, including geographical. Booth ended up decamping that October from the couple’s Georgia residence and returning to Memphis, where he had moved with his parents in 1959, studied at Memphis State University (now the University of Memphis), and lived for many years, finding our blues-soaked Delta capital to be the source of many of his early subjects and inspirations.

Memphis was also the scene of numerous frustrations for Booth over the years and would continue to be even after his return. He rented a house on Belvedere and, in short order, became destitute. He befriended a homeless man, who had taken up residence in an outdoor shed. As the weather worsened one winter, Booth invited the man to come in out of the cold and spend time in the house.

The man did, and, as Stanley tells it, “he went on to steal my car and a bunch of other stuff.”

Over the last few years, his lifetime achievements seemed to have come to nought. He recalled: “You can’t eat reputation. If I had a nickel for every good review I’ve had …” he said, letting that sentence fade out rhetorically. He had lived for several years in the Arkansas Ozarks, where he had holed up in a cabin with the aforesaid Charlie Brown and written much of his Stones book, and that experience suggested a strategy.

“I was thinking of getting out, packing a bag, and going to the Ozarks, to a cave. I had worried about becoming homeless when I was on Belvedere. I was out of money, thinking seriously of going to Arkansas and living in a cave. I know where several caves are that maintain a temperature of 65 degrees inside, year-round.”

Instead, Booth ended up using the life insurance money left him by Blakely to buy his current house, a modest brick bungalow in the vintage Vollintine neighborhood, among largely African-American neighbors. He remained carless, as indeed he is today, dependent for transportation on others.

Here is the appropriate spot for a little backstory. Stanley and I, both English majors at Memphis State in the ’60s, with similar tastes and vague aspirations to be famous writers, had gotten to be fairly close friends, it’s fair to say — though there was always an element of rivalry, both as fledgling wordsmiths and in other ways common to greedy and needy undergraduates of our sort. Let me confess: He was much more the classic stud, though he surprised me recently by expressing envy, ex post facto, about a time or two I’d gotten lucky.

After graduation, we stayed friendly. When I had an optional operation to remove a benign bone tumor, discovered during a brief stint in the Air National Guard, my first post-operative visitor outside my immediate family was Stanley Booth, who brought me flowers(!) and stayed for a while, meanwhile charming my mother and grandmother.

We had both thought of fiction as the likely arena of our development — he a Hemingway acolyte, me fixated on Fitzgerald — but I would get a series of post-graduate jobs as a journalist (with, sequentially, the Millington Star, the Blytheville (Ark.) Courier News, and the Arkansas Gazette), and Stanley, too, in those years of the New Journalism, moved into the province of non-fiction, setting out with deliberation to master the art by tackling the subject of the street sweeper and indigenous Memphis blues artist, Furry Lewis, to whom he was introduced by Brown.

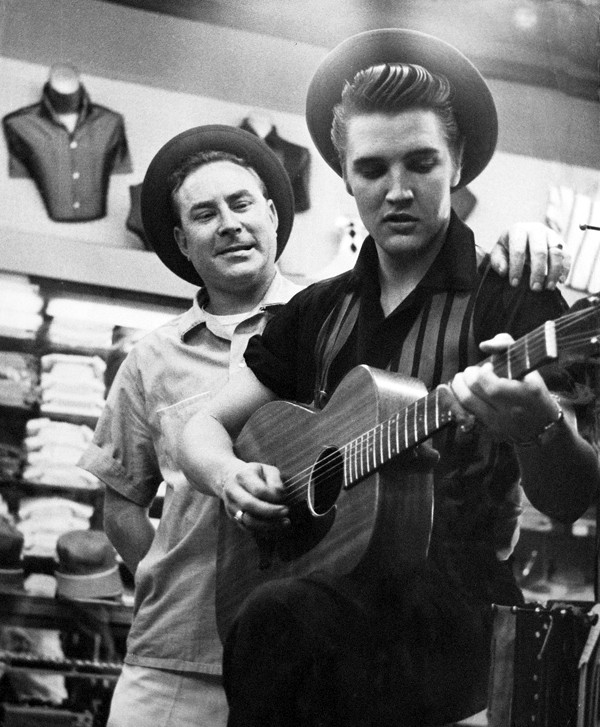

Stanley tried unsuccessfully to sell that article to Esquire, the magazine which then was the epitome of hip to young writers, and was told instead that the magazine was looking for someone to write about Elvis Presley. The Furry Lewis piece, shelved, would later be published by Playboy, which would give it that magazine’s award for non-fiction article of the year. Meanwhile, Booth cast about for some way of getting close to Presley, then still in the premature mummification of B-movie Hollywood.

That’s when Stanley connected with Dewey Phillips, looking for an entree to the reclusive Elvis that the disc jockey could no longer provide. And one night — this was the summer of 1967 — Stanley and I dropped some acid and killed an evening at the East Memphis apartment complex where he was then living. As he knew, my family had, for a period of months, when the young Elvis had begun to score as a Sun Records artist, lived next door to the entertainer and his parents, who were then inhabiting a modest house on Lamar Avenue.

Years later, my brother Don and I had ended up at Graceland for an evening, in the company of a veritable mob of hangers-on, and on this evening in 1967, years later, I told Stanley about that and much else that I remembered about Elvis. I related in some detail a story from that surreal night at Graceland, focused around my brother’s nervously playing Elvis’ piano in the wee hours, under the gaze of a just-awakened Elvis, followed by the whole crowd’s going outside to watch the icon’s largely futile attempts to fly a model airplane.

That story, rendered with artful third-person objectivity, along with my recollections of a key Presley concert at old Russwood Park, would end up as the borrowed centerpieces of an Esquire article that would put Booth on his way. The article, entitled “Hound Dog, to the Manor Born,” was masterful, insightful, and wholly deserving of the classic status it achieved almost immediately and maintains today. Its writing owed much to the example of Gay Talese, an avatar of the New Journalism who had demonstrated in a previous Esquire article entitled “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold,” how one could write a profile without access to its subject, by dint of patient and probing interviews with other people who had enjoyed such access.

Out of necessity, the story lacks a characteristic ingredient of virtually everything else Stanley has written, a focus on his own experience as a major leitmotif in whatever he has to say about his avowed subject. Open any page of The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones at random, for example, and you are as like to find an account of Stanley’s entertaining a passage with a lady friend as you are one of his brilliant evocations of the Stones in concert or on the prowl.

With the exception of that first Esquire article, a virtuoso effort of third-person sculpting, virtually the whole of the Stanley Booth canon is, in one sense or another, autobiographical. Though here and there a reader or critic may have carped at the method, with its component of Booth zingers and quips, picaresque moments, and wholly personal recollections, it generally works to its author’s purposes, though I have always thought its enforced absence from the Presley article is what made for a clean launch of Stanley’s career.

An ironic after-effect was that, when Elvis died in 1977 and it came time for me to do my own tribute to the King, published in Memphis magazine (then called City of Memphis) as “Elvis: End of an Era,” I deemed it advisable to eschew the first person, a fact that redounded to the credit of my piece, too, which I believe has also achieved some stature, though not to the scale and circulation of Stanley’s.

Incidentally, my other direct (and very temporary) involvement with a Booth opus would come in 1982 when Stanley, still struggling to fulfill a contract for a book that was already more than a decade overdue, found himself surrounded by unassembled masses of typescript of Stones material, including complete histories of the band and its members and memorable experiences with it and them, especially on the fateful 1969 tour that ended at an Altamont, California, free concert maimed by murder and mayhem at the hands of the Hell’s Angels.

I volunteered my help on the editing side, and he entrusted me with the seeming thousands of pages, along with an authorizing letter. To my later regret, and probably to his ultimate benefit, I procrastinated on the awesome task of collation, and he retrieved the whole mass of materials and bore down all the harder on the task of making a book out of them. It was a truly sink-or-swim effort, and within a year’s time — aided, he has said, by structural advice from the old Beat writer William Burroughs — the final mammoth manuscript of The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones was finally ready, justly to be called a classic, though it bore the unhelpful title Dance with the Devil when first published by Random House in 1984.

Now available in various editions under its original title, the book compellingly renders not only its stated subject and the ethos of the ’60s but contains unique insights on the nature of humanity and life itself on every page. It’s a hell of a read.

But the true adventures of Stanley Booth himself had, as mentioned, stranded him in a kind of limbo of late. Though he would occasionally be summoned forth as a sort of human artifact, as when he gave a well-received reading from his work at the Stax Museum in October, he was largely home-bound in his residence on North Idlewild, living a kind of hermit life within its walls, overseen by large framed photographs of Lash LaRue by his friend Bill Eggleston.

In his youth, Stanley had been quick and agile, the possessor of a black belt in karate. Now he was not only stranded without wheels, on those occasions when he did get about, he was still dapper but traveled slowly, aided by a cane, a white-maned gentleman severely hobbled by rheumatoid arthritis. The prospect, born of desperation, of his going to live in a cave in Arkansas, was sheer folly, a gallant affectation but just that, an affectation. But his mind still ground on, exceeding fine, anticipating new opportunity and waiting out adversity, like a lion in winter. His pride was fully preserved.

I took him to a restaurant some months ago, and when another diner, a young woman, approached our table, brandishing some cards and asking, “Do y’all know what tarot is?” his prickly side emerged. “Do I look like a child?” he thundered, insulted by the woman’s presumption and forcing her to retreat.

More recently, however, on the day after he was told by his agent that his new collection, Red Hot and Blue, had been accepted for publication, he got further good news when a gentleman in Adelaide called him and asked him if he would consider traveling to Australia and delivering a series of readings in the cities of that continental nation, to the tune of, say, “ten to twenty grand.”

We went out to eat a couple of times this past weekend, and Stanley was courtliness itself to the waitpeople and passers-by. After an evening at The Green Beetle, the South Main bistro once frequented by the late Dewey Phillips, he told a young husky-voiced waitress that she ought to “cut a blues record, right now.”

On the way to his home, he told me something I hadn’t known and would never have expected, that he had converted to Catholicism some 30 years ago and, in so doing, had experienced “the greatest pleasure of my life … a complete redesign.” I dropped him off at his house, where we did a hand-slap of farewell, and he said, “I’m 76 years old, very happy to have survived to this point, and I ain’t mad at nobody.”

An article about Memphis photographer Bill Eggleston from Booth’s forthcoming new collection, Red Hot and Blue, will be soon published in the Flyer‘s sister publication, Memphis magazine.

COURTESY OF LANSKY’S ARCHIVES

COURTESY OF LANSKY’S ARCHIVES