For artists, self-portraits have been a way to explore form, movement, and representation with the most accessible model around: the self. As technology has advanced, the length of time required to create a portrait of oneself has significantly been reduced. If you have a camera or smartphone, you can snap your own image in an instant. Access to additional features allows you to also manipulate the image in countless ways.

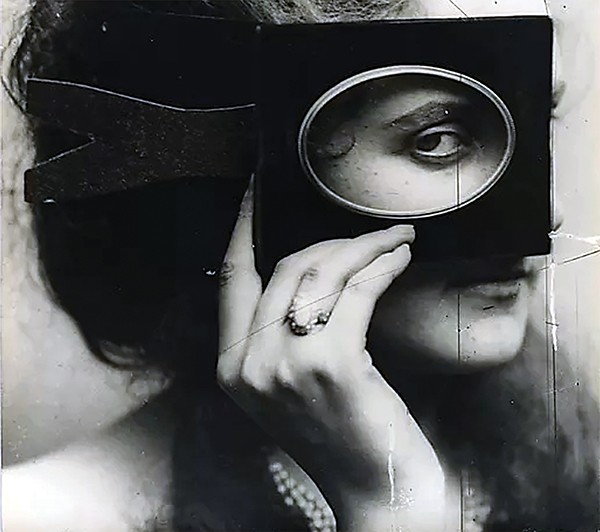

Photography was introduced in 1826, and in the 19th century, it was a luxury. However, for the young aristocrat Countess de Castiglione, time and money were no match for her creative drive. Collaborating with photographer Pierre-Louis Pierson, the countess created over 400 photographs of herself. The exhibit “Countess de Castiglione: The Allure of Creative Self-Absorption” at the Dixon Gallery and Gardens recently had on display more than 30 pieces of her work. Though Pierson managed the camera, I learned that it was the countess who was the director. She made the decisions on the poses, the costumes, and the props in each photograph. These were her selfies.

Countess de Consligliore

Some argue that self-portraits should not be confused with today’s selfies. They insist that self-portraits have a precision behind them that is lost in selfies. While selfies are more immediate in their results, that doesn’t take away from the thought that can be put into things such as framing and lighting. Take anyone who has posted “golden hour” selfies on social media and they’ll tell you, lighting is key. On the other end, contemporary artist Ai Weiwei has multiple selfies he’s shared. When asked to take selfies with others, he insists on holding the camera. He calls himself the “the best selfie artist.”

What remains constant is how art is used to create a representation of someone. What changes is the medium and who controls it. Many agree that the countess was obsessed with her representation and that her photography was motivated by her narcissism and self-absorption. She went into debt financing her photographs. Though she did share some of her work, much of it was for her private collection. Undeniably, however, she pushed not only photography as a form of art in its early years but also women’s role and agency in self-representation. The countess’ authorship in photography was her practice of being able to express and represent herself on her own terms at a time when a woman’s image was mostly controlled for them.

Still today, we are uncomfortable with women’s control over their image. Maybe this is part of what unsettles us about selfie culture — people controlling their image often in a way that is counter to what is prescribed to them. In her experimentation with self-expression, the countess created how she wanted to be captured in the moment and remembered in time.

This is a lesson we can take from her. Be fearless in your self-expressions, whether you keep them private or make them public. Maybe take selfies like Ai Weiwei. Find art and beauty in your daily life and don’t jump to judge others when you see them being their honest self.

Art is always changing. Photography in the early years after its invention was not considered art. Technology has allowed us to photograph and record at any moment. We don’t necessarily consider selfies an art, but artists like Ai Weiwei have incorporated it into their art practice. There have even been exhibits that specifically drew from selfies made with mobile phones. People today use selfies as a form of art and expression in ways that may not have been conceivable when “selfie” was widely introduced as word in 2013.

Selfies, over time, are probably going to change in use and meaning in the same way self-portraiture and photography have. Perhaps opening up what are considered accepted mediums of art can help us find new artists that help us see the world in a new way.

Aylen Mercado is a brown, queer, Latinx chingona and Memphian exploring race and ethnicity in the changing U.S. South.