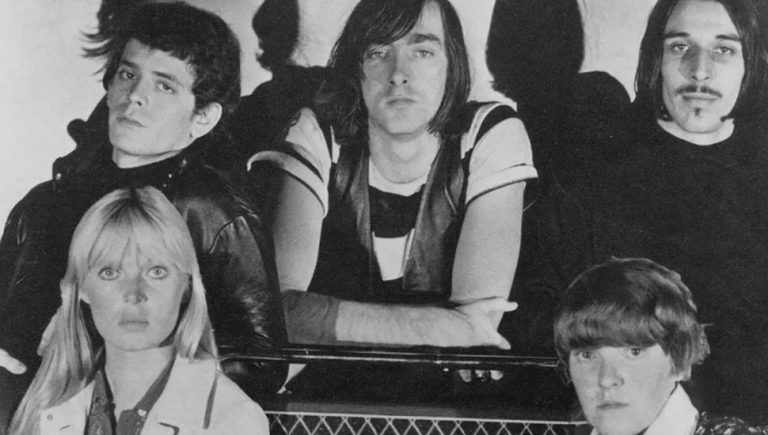

When John Lennon was shot in front of his apartment at New York City’s Dakota building in 1980, Time magazine called it an “assassination.” Noting that the term is usually reserved for the murder of a head of state, the Time editorial board called Lennon “the leader of a state of mind.” Before his murder by a deranged fan, Lennon was a musician — albeit one of the most famous in modern history. Afterwards, he became a martyr.

But martyrdom, it turns out, does not suit Lennon. Sure, they open every Summer Olympics with his secular hymn “Imagine,” but the Beatles Backlash is real, and Lennon’s legacy has gotten the worst of it. Sir Paul McCartney is still playing shows and wowing audiences at age 82. Ringo is still the floppy mascot guy he always has been (and, let’s be clear, one of the greatest drummers of all time). George Harrison’s solo work is now venerated as the best of the post-Beatles output. But spend a few minutes on any social media network these days and you can find people who say the Beatles were massively overrated, and, most cruelly of all, John Lennon would probably be MAGA if he were alive today.

Lennon the iconoclast would have understood. A couple of generations have had the Fab Four’s music shoved down their throats by the Beatles industrial complex. That the band “changed the world” is a Boomer catechism. So when young people hear the music made by a bunch of moldy old white guys, of course they’re predisposed to hate it.

In One to One: John & Yoko, director Kevin Macdonald aims to demystify Lennon and reveal the human being behind the mythical martyr. The meat of the film is performance footage from Lennon’s Madison Square Garden show on August 30, 1972. The concert was a benefit for the victims of the Willowbrook State School in New Jersey, which journalist Geraldo Rivera had exposed as a hellhole where developmentally disabled children were basically imprisoned and left to rot. It was the only full-length concert Lennon played after the Beatles’ Shea Stadium swan song in 1966.

The shocking footage from inside Willowbrook is a part of the hundreds of clips from TV and film that flesh out One to One. Macdonald begins the story in 1971. The Beatles have been broken up for more than a year, and John Lennon has been living with his new wife Yoko Ono in a posh English country estate outside London. As Lennon recounts in a taped interview with a print journalist, Ono was the one who hated living in a mansion and wanted to simplify their lives. On a short vacation to New York City, Lennon and Ono discovered that they loved the hustle and bustle, and the cultural scene. Lennon tells the interviewer that he felt at home because “no one bothered us.” So the couple sold their English estate and moved into a two-room flat in Greenwich Village. There, they mostly smoked weed and watched the TV they had propped up at the foot of their bed, which had been left by the apartment’s previous owner.

A couple’s therapist would have a field day with the picture of John and Yoko’s relationship Macdonald draws. The “Yoko is the villain who broke up the Beatles” narrative was exposed as misogynistic agitprop by Peter Jackson’s epic Get Back documentary series. Jackson found a sound clip where Sir Paul himself calls bullshit on the notion that the group was in trouble because “Yoko sat on an amp.” But Lennon and Ono were clearly codependent, years before the psychological term was coined. By the time they moved to New York, they had both gotten hooked on heroin and kicked the habit. Lennon was tired of being a prisoner of his own fame and fascinated by the avant-garde art world which had embraced Ono, whom he called a “creative genius.” (One of the film’s running gags involves taped conversations between Ono’s staff who are trying desperately to secure a thousand house flies for one of Ono’s art installations.) In a clip from one of the panel-type talk shows that was popular on TV at the time, Lennon opens up about being abandoned by his mother and reconnecting at age 16, only months before she was hit by a truck. For her part, Ono was the daughter of a rich Japanese family who had been made into destitute refugees by the American firebombing of Tokyo. It’s no wonder that two people with abandonment issues would cling so fiercely to each other.

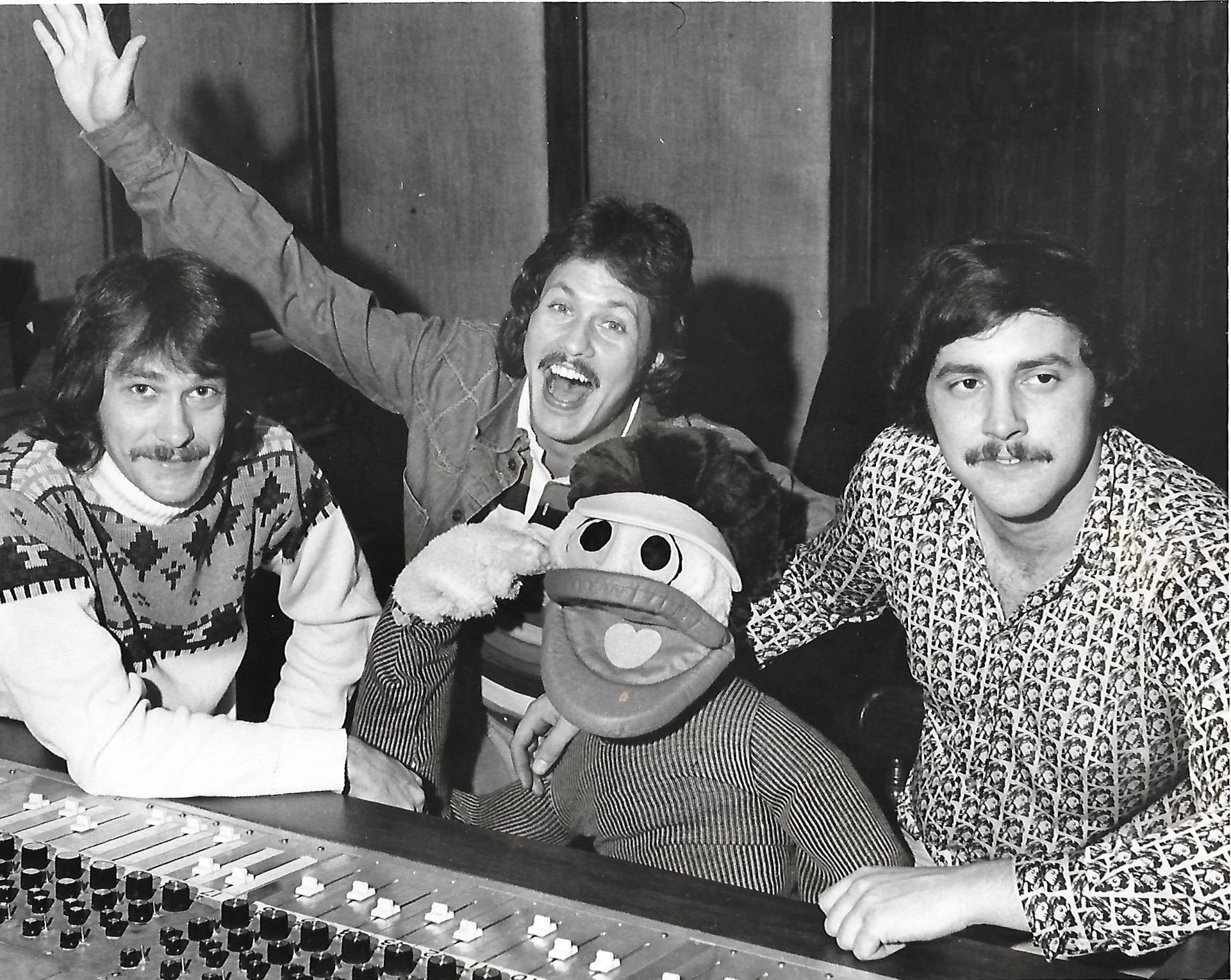

The focus of their lives in 1971 to ’73 was radical leftist politics. Ono’s feminism was a revelation to Lennon, who had been abusive to his first wife Cynthia. Macdonald drives the point home by showing footage of Lennon getting kicked out of the First International Feminist Conference, where Ono was speaking, for being the only man there. Protests against the Vietnam War were raging in America, and the Ono-Lennons were in the thick of it. They were planning an American “peace tour,” where some of the proceeds would have gone to bail funds for imprisoned Black men. Lennon tried to recruit Bob Dylan as a co-headliner but never quite got it done. He wrote a song about the Attica prison revolt that his manager begged him not to perform in public. In the end, the tour plans fell apart. Three months after the Plastic Ono Band’s MSG show, Nixon was reelected in a landslide, and his State Department tried to deport Lennon. The restored concert footage shows what might have been. Lennon and the band (which includes a bass player dressed as Jesus and a Stevie Wonder guest vocal on “Give Peace a Chance”) are loose and playful. Lennon delivers a transcendent version of “Imagine” at a piano while casually chewing gum. One imagines a world where, with a little more practice, they coalesced into a touring powerhouse that freed prisoners across the country. But that is not the world we got.

One to One: John and Yoko

Now playing

Malco Ridgeway

courtesy Andy Black

courtesy Andy Black  courtesy Andy Black

courtesy Andy Black

Courtesy of Last Bite Films.

Courtesy of Last Bite Films.