It’s July 2018, and the Orpheum Theatre in Downtown Los Angeles is teeming with activity. The old movie palace’s basement is packed with background actors getting dressed and made up in ’70s finery — bell bottoms, afros, and clashing patterns — to appear in Dolemite Is My Name.

On one side of the cavernous lobby is “video village,” where technicians, producers, and crew huddle around monitors, adjust controls, and clutch headphones to their ears, watching the action onscreen. On the other side of the lobby, director Craig Brewer and cinematographer Eric Steelberg are setting up a tracking shot with a pair of stand-ins. Once they’re satisfied that the complex choreography of camera, lighting, and extras is right, a call goes out from the assistant director. “Clear the set.”

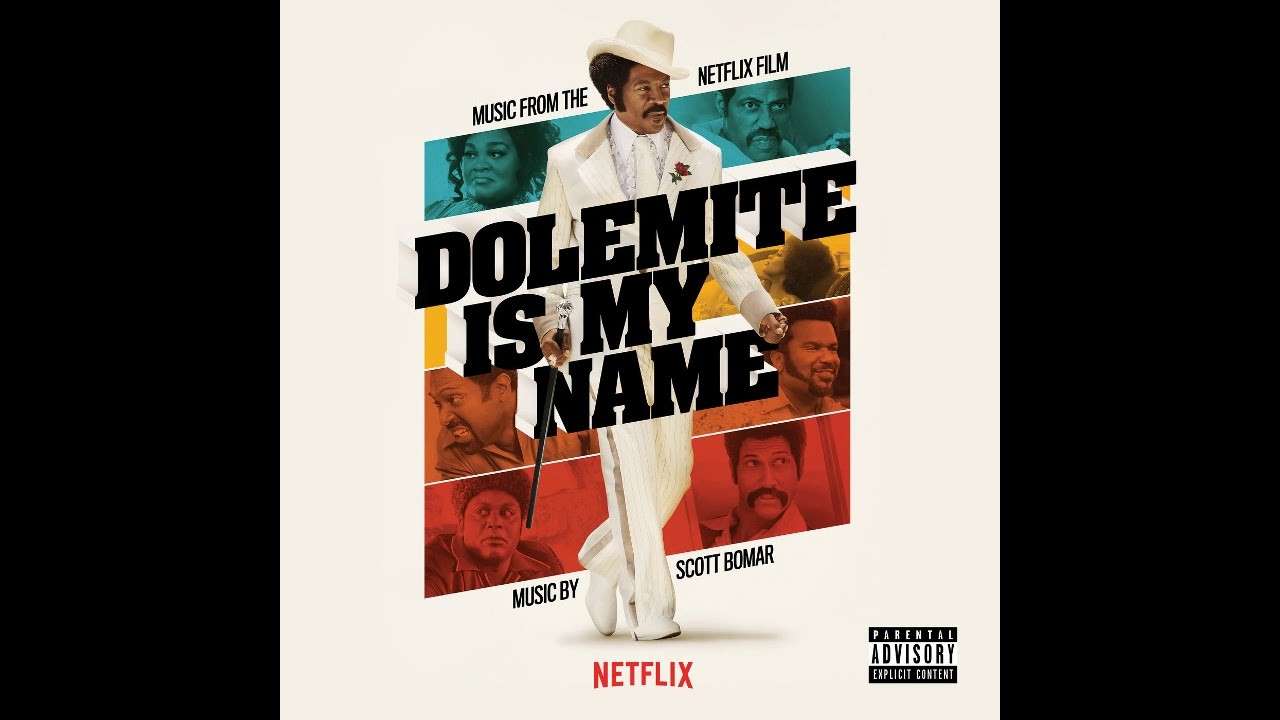

Eddie Murphy as Rudy Ray Moore

Eddie Murphy is ready for his close-up.

You Can’t Remake Dolemite

A year later, Brewer is on the phone in Brooklyn, where, the day before, he shot scenes for Coming 2 America with James Earl Jones. Dolemite Is My Name has just had a triumphant premiere at the prestigious Toronto International Film Festival, with the first audiences raving about Murphy’s performance. I ask Brewer how he came to helm the film for Netflix.

“I had heard that there were rumblings that they were trying to remake Dolemite. As much as my mind always tries to go to a place of, ‘How can Dolemite be remade?’ There’s the basic story of a man who’s in prison, who, for whatever reason, is let out, now into a different world, where everything he had is now under the control of somebody else … then I thought, ‘Craig. Stop. Footloose, maybe. Some other movies, maybe. But Dolemite is special because it’s funny.’ You can’t just do an action drama out of Dolemite. It’s beautiful because of its production flaws, and that’s why — especially among independent filmmakers — we love it so much. Of all the blaxploitation movies, it’s perhaps the most incredulous and head-scratching. I can’t even think about doing a Dolemite remake.

“Then my agent called me a year later and said, ‘We have the script called Dolemite Is My Name, and I think you should read it.’ I don’t think I’m the guy for it because I just don’t think that it can be redone. He said, ‘Wait a minute. This is a script from Larry Karaszewski and Scott Alexander. It’s about Rudy Ray Moore making Dolemite, and Eddie Murphy’s going to play him.’ And I said YES! He said, ‘Well I think you should read the script first, and I think you should talk to the producers …’ And I was like, ‘Of course, but if you’re looking for my response, I’m in.'”

Craig Brewer, Scott Alexander, and Larry Karaszewski at the Los Angeles premiere of Dolemite Is My Name

Everything

Falls Apart

Rudy Ray Moore grew up the son of a sharecropper in Fort Smith, Arkansas. As soon as he was old enough, he moved to Los Angeles to try to make it in show business. He tried first as a singer, then as a comedian, then a combination of both, before he created the character of Dolemite, a big-talking street pimp whose rhyming braggadocio translated into a series of hit “party records” — comedy routines often backed by slinky soul music, packed with dirty words, street wisdom, and transgressive situations. After a series of unlikely, underground hits (which included a Dolemite Christmas album), he leveraged his fame in the African-American community into making an independent movie based on the character. At the time, the term for films aimed at the inner city markets was “blaxploitation.”

“What makes Dolemite so special is that it’s one of a kind,” says Karaszewski. “A lot of the blaxploitation movies are trying to be sort of generic action pictures with African-American leads. That made them special and cool because you hadn’t seen African Americans in those roles before, where they were tough cops. But Rudy’s movie goes to another level on top of that. He’s making fun of the genre, while also trying to be the genre at the same time. He’s a comedian. They were meant to be laughed at. But they were also meant to be, ‘Look at that! It’s a cool car chase!'”

Karaszewski and his writing partner Alexander met in film school and have been working together for more than two decades. They often finish each other’s thoughts. “Shaft, Superfly, Black Caesar are kind of urban action films,” Alexander says. “They’re taking their leading men seriously. They’re cool, they’re good-looking, they’ve got good-looking chicks, the gun, and the suit. Rudy is a doughy comic who is not an actor, and he cannot do kung fu. But he was making the movie he wanted to see. He wanted to have kung fu and ladies and car chases. …”

“… and he made it through sheer force of personality,” says Karaszewski. “It comes out on the screen.”

Alexander and Karaszewski wrote the 1994 classic, Ed Wood. Directed by Tim Burton and starring Johnny Depp as the real-life “worst director ever,” the film earned an Academy Award for Martin Landau’s portrayal of the original Dracula, Bela Lugosi. “When we meet big-time, successful directors, a lot of times they’ll pull us aside and say, ‘I feel just like Ed Wood.’ That’s the whole point of the Orson Welles scene toward the end of the movie. It doesn’t matter if you’re the best filmmaker of all time or the worst filmmaker of all time, you still have the same problems,” says Karaszewski.

Among the fans of Ed Wood was one Eddie Murphy. When the man who saved Saturday Night Live, the star of Beverly Hills Cop, Trading Places, and Coming to America, saw the film in the mid-1990s, he called up Alexander and Karaszewski with a proposition. A week later, the three of them were in a room with Rudy Ray Moore. “He told us what he would like to see in a movie about his life and that Eddie would be perfect for the part,” says Alexander. “We thought, ‘Oh my god, this is going to be the greatest movie of all time!’ And then it just fell to pieces. That’s what happens in Hollywood — you get excited, and nine times out of 10, nothing happens.”

(l-r) Craig Robinson, Keegan-Michael Key, Eddie Murphy, Tituss Burgess, and Mike Epps

Stuck in Turnaround

Craig Brewer knows that feeling. He’s been riding the Hollywood roller coaster since 2005, when Hustle & Flow became a breakout hit at the Sundance Film Festival. The film, which Brewer fought for years to get financed before producer John Singleton rode to the rescue, set a record when it was bought by Paramount for $9 million in a late-night, Park City, Utah, bidding war. It went on to win an Academy Award for Three 6 Mafia’s “It’s Hard Out Here for a Pimp” and earn a Best Actor nomination for its star, Terrence Howard.

For a movie made on a shoestring budget in Memphis, Hustle has had an extraordinary cultural impact, becoming a staple on cable television and inspiring Memphis Grizzlies fans to adopt “Whoop That Trick” as an unofficial fight song. The scenes of Howard, Taraji P. Henson, DJ Qualls, and Anthony Anderson creating music in a North Memphis shotgun house have been copied endlessly by filmmakers looking to create inspirational moments.

Brewer’s controversial next film, Black Snake Moan, gave Samuel L. Jackson one of the best roles of his long career and introduced the phrase “chained to the radiator” into the lexicon. Brewer gained a reputation as an excellent script doctor, and, in 2011, he was tapped by Paramount Pictures to remake their seminal 1984 dance movie Footloose. The next year, he stepped in as executive producer to save the troubled Katie Perry movie Part of Me, and it became the seventh-highest grossing documentary of all time. He was clearly Memphis’ most successful filmmaker and had an enviable career by any Hollywood standards.

After Footloose, Brewer was attached to write and direct The Legend of Tarzan for Warner Brothers. It was to be his introduction into the exclusive club of directors trusted with $100-million budgets. He wrote a screenplay that turned heads in Hollywood, but studio politics tore the production apart, and, amid spiraling budget estimates and executive turmoil, the project was shelved. When The Legend of Tarzan was eventually completed in 2016, Brewer’s script formed the backbone of the picture, but he still had to fight for his screenwriting credit.

What the public didn’t see were the dozens of projects that never got off the ground. There was Maggie Lynn, a music epic Brewer wrote about a country singer rocketing to fame; there was Mother Trucker, a script about the infamous Tennessee inmate who broke out of jail and stole Crystal Gayle’s tour bus in an effort to visit his dying mother. He pitched a Star Wars movie to Lucasfilm honcho Kathleen Kennedy and a reboot of The Creature From the Black Lagoon to Universal. Nothing gained any traction.

At the same time, his long marriage to wife Jodi Brewer was on the rocks. The pair eventually separated but did not divorce. Brewer felt like his life was falling apart. “I bought a big house,” he says. “I bought into a lot of the trappings of being a successful filmmaker. And then suddenly, some of those things began to dry up, and I got very scared. … Movies have been going through such a change, and I was beginning to get really bitter about it. Tarzan and that whole developments situation was not ideal, and I had been trying to get these other movies going with the studio system, any way I could, and it just wasn’t happening.”

It was friends from his past who brought him back. In 2015, Terrence Howard and Taraji P. Henson, whom Brewer made stars in Hustle & Flow, became the lead actors on Empire, a wildly successful Fox show created by Lee Daniels. “I would say it’s quite true that if John Singleton helped start my career,” says Brewer, “Lee Daniels helped bring me back.”

Daniels hired Brewer for the second season of Empire. “I wanted to be in a room working with a bunch of other writers. I wanted to be on set filming somebody else’s vision. I’d like to just be a director and just be a writer for a while and help the product be the best it can be and hopefully bring my best to it. It was just so fortunate that I got to do Empire. I loved the show so much, and I loved what Lee had created: his beautifully subversive, outlandish antics that I think break down walls, not just with race, with culture, with class, but just what people would think is appropriate.”

Brewer worked in the Empire writer’s room for three seasons, directing 10 episodes. Brewer says he found his joy “just writing scripts, being in a room with a bunch of creative people, and learning to listen, trying to not perform all the time.”

Dolemite has a star-studded cast — Snoop Dogg (top) plays a radio DJ; Craig Robinson (below) plays Ben Taylor in Dolemite Is My Name.

“Does Eddie Really Want to Do This?”

In 1996, Alexander and Karaszewski wrote The People vs. Larry Flynt. “We had such a good time shooting that movie in Memphis,” says Alexander. “We got to know D’Army Bailey. He was a blast. As soon as [director] Milos Forman met him, he said, ‘Let’s turn him into an actor.'”

Later, Karaszewski would become a regular at the Indie Memphis Film Festival, serving on juries and just coming back to have fun and watch movies. In 2016, Alexander and Karaszewski wrote and produced the 10-episode miniseries The People vs. O.J. Simpson for the FX anthology show American Crime Story. It became a ratings sensation and was nominated for 22 Emmy Awards, ultimately winning nine, including Outstanding Limited Series and awards for actors Sterling K. Brown, Sarah Paulson, and Courtney B. Vance.

“After we did the O.J. thing, a lot of people wanted to do projects with us,” says Karaszewski. The writing partners decided to use the opportunity to revisit some dream projects that had failed to launch, like the Rudy Ray Moore story. “We had producers John Davis and John Fox contact Eddie to see if he was still into this idea. Not only was he ready, he was eager. That’s how we got to Netflix.”

Murphy, who was semi-retired, wowed the Netflix executives at the pitch meeting. “Eddie is very open about this,” says Alexander. “He says, ‘I was just enjoying sitting on my couch, playing with my kids, and hanging out.’ He has a whole brood. Coming in to Netflix, they said, ‘Does Eddie really want to do this?’ So Eddie showed up at the Netflix meeting and summoned his superpowers. He turned into Rudy and started doing ‘Signifying Monkey.’ The Netflix people were like, ‘Holy shit! This is for real!’ Larry and I barely opened our mouths in that pitch meeting. You got Eddie in the room doing it. What more do you want?”

Karaszewski suggested they talk to Brewer for the director slot. “It was my first time meeting Craig, and I was blown away,” says Alexander. “He said, ‘It’s a movie about duality’, and no one else had actually said that out loud.”

The Man Who Was Fearless

Once word of Murphy’s commitment to the project got out, Keegan-Michael Key signed on as Jerry Jones, the playwright Moore enlists to script his dream project. Chris Rock and Snoop Dogg got cameos as DJs who helped Moore in his career. Mike Epps and Craig Robinson became members of Moore’s entourage. But the biggest get was Wesley Snipes as D’Urville Martin, the blaxploitation star who appeared in Black Caesar and whom Moore cajoled into directing Dolemite.

Brewer says he came to identify deeply with his subject. “Rudy Ray Moore made his own records. He forged his own path. I couldn’t help but feel a connection to it. There were many times that I thought, I know that because of the material that I’m drawn to and even the mentors in my life, like John Singleton and Stephanie Allain, and more recently Lee Daniels, I know that there’s a lot of material that I have that has predominantly African-American stories, and I did begin to second-guess whether or not I’m a person to tell this story. But I couldn’t help but see all of my connections to it. I couldn’t help but see a guy in Los Angeles from the South with doors slamming in his face, basically turning to a rag-tag group of friends and saying, ‘Well, what if we just did it anyway?'”

Brewer came to see the duality of the character was central to the story’s appeal. “I think it’s important for all the artists that I’ve had in my life. I get excited thinking about Rudy Ray Moore through the lens of Al Kapone and Harlan T. Bobo. I think I have a side of me that wants things to be larger than life — big music that hits right on an edit. But there is another side of me that’s at times insecure and wanting reassurance from friends and family around me.”

Without his Dolemite costume, Moore “just looks like a normal, nice guy. Then you put on that wig, that hat, that jacket, and that cane, and the idea that he could escape into this man who was fearless ultimately helps that man who has fear,” Brewer says. “There are times that the whole ‘fake it till you make it’ is a healthy program when you’re trying to begin something.

“It’s also something I see in Eddie’s work. I wouldn’t say there are two personalities, but there are definitely two sides of the same coin. It’s there in The Nutty Professor, in Coming to America, definitely in Trading Places. It’s also in Eddie’s personal manner. He’s a very real, intellectual, soft-spoken man who doesn’t feel a need to perform for everybody in the room until it’s time for him to perform. Then this iconic entertainer suddenly emerges, and you’re like, ‘Wow! Where did this come from?'”

Karaszewski says Brewer’s direction was integral to the final product. “I remember one of the first days on the set, we were filming one of the scenes from the chitlin’ circuit montage. I was standing there with Scott and said, ‘Thank god we actually got someone who knows what it looks like.’ Craig has been to these places. He knows that the signs with the booze specials have half the letters missing. He knows that there’s a smoker out in the back parking lot smoking some ribs and brisket. It has that lived-in feel. That was always our fear, that someone would take the script and make the superficial version of the story. It is very easy to make fun of the fact that Rudy is making a bad movie. What Craig did was add that realness that gave the movie a humanity.”

Alexander says the production had a joy to it that is rare in the high-pressure Hollywood world. “Being on his set was a blast. Craig created such a positive environment, it was a total joy to be on the set each day. Sometimes, actors who weren’t even working were just kind of hanging around. When we were shooting the closing shot of the movie, which is a big, elaborate crane shot, Craig had a little boom box where he would play music and sync it up. Eddie would do the take, then everyone would huddle around the monitor and Craig would say, ‘Let’s do playback!’ And he would do it with the music. It was like we were getting to watch the movie in real time! It was just so fun.”

For Brewer, who had set so many of his films in Memphis, getting to shoot in L.A. was a dream come true. “We’re in Griffith Park, up in the mountains, and doing a ’70s car chase scene, where a police car is chasing Dolemite’s car, sirens blaring, everything. I call action, and we’ve got two cameras going, and the car’s tires are squealing around the corner. I yelled ‘cut’ and just started going ‘Whoo hoo! Yes!’ I turned to the crew and said, ‘I’m sure y’all have probably filmed thousands of car chases. That was my first, and it couldn’t have been better!'”

A Dream Picture

Coming 13 years after being nominated for Best Supporting Actor in Dreamgirls, Eddie Murphy’s performance in Dolemite Is My Name is a revelation. He’s funny, of course — Murphy and his late brother Charlie were doing Dolemite routines while they were pre-teens — but he is also vulnerable, as in the opening scene when he’s trying to get a DJ, played by Snoop Dogg, to spin his lame R&B records.

The script is the spiritual successor to Ed Wood, telling the story of Moore’s transformation from a record store clerk and flailing nightclub comic to a comedy legend. Not only is Murphy good, but the deep cast of Moore’s collaborators all have fleshed-out characters to play. Snipes is perfection as the drunk director who bolts at the first hint that something better is coming along. Da’Vine Joy Randolph is a big discovery as Lady Reed, Dolemite’s partner in crime. Keegan-Michael Key gets laughs as the intellectual straight man to Moore’s outlandish street performer. Memphian Claude Phillips, who has been in every Brewer movie since Hustle & Flow, cameos as a hobo who teaches Moore the rhyming cadence that would eventually make him known as one of the godfathers of rap. Scott Bomar, Memphis musician and producer, composed the soulful score, which was recorded in Memphis.

“We were trying to make a fun, entertaining movie,” says Karaszewski. “We didn’t realize how audiences would take it as inspirational. They look at the can-do spirit of Rudy Ray Moore. If someone closes a door in his face, he will open up another door. There’s so much comedy in the movie, but the inspiration is played sincere and played honest, so audiences come away with that.”

Brewer says Murphy’s performance was the key to getting the film’s tone exactly right. “I am sure it’s possible to make a Martin Scorsese-style, darker examination of Rudy Ray Moore. I just don’t know if that’s really the spirit of Rudy Ray Moore. He was really happy. He was about entertainment and fun, but I think we have the appropriate amount of vulnerability in the movie. Eddie is not just in it for the yucks. He’s portraying a very real character and somebody who means a lot to him because he was a huge fan. It’s been a dream of his to make this movie for more than a decade.”

For Karaszewski, Craig’s background as a scrappy indie filmmaker who broke into the Hollywood system made him the perfect person to helm Dolemite Is My Name. “No one was going to hand Craig Brewer or Rudy Ray Moore a bunch of money to go make their dreams come true, so they had to do it themselves.”

Courtesy Memphis Music Hall of Fame

Courtesy Memphis Music Hall of Fame

Amazing Grace LLC

Amazing Grace LLC