United Way

United Way

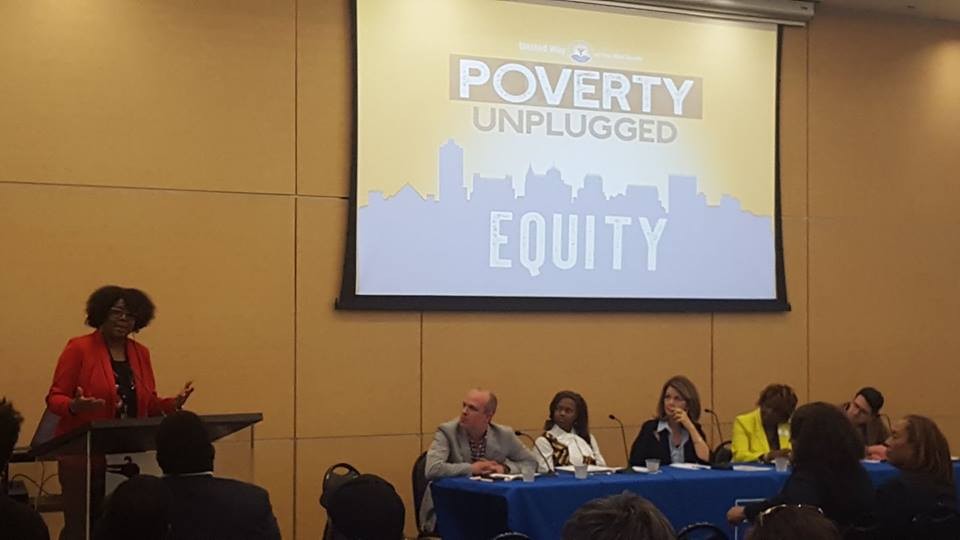

Panelists featured in the series’ first installment on equity

A community conversation about poverty and education is scheduled for Tuesday, July 17th at the National Civil Rights Museum (NCRM).

It will be the second of three installments in Poverty Unplugged, a series of solution-oriented, community conversations. Hosted by United Way of the Mid-South, the series looks at the intersection of poverty in three different areas.

Tuesday’s installment will focus on access to education and how it can aid personal development. It will also consider the amount of funding in communities that goes to education, if it is enough, and if the funds should be split into other areas.

The panel will consist of Mark Sturgis, executive director of Seeding Success; Danny Song, founder of Believe Memphis Academy; Shante Avant, deputy director of the Women’s Foundation for a Greater Memphis; and Tami Sawyer, local activist and director of diversity and community partnerships for Teach for America.

“Access to an equitable education is still one of the challenges facing our city and

country today,” Sawyer said. “We’re hoping we can bring light to what’s keeping Memphis children from quality education and what practices and solutions we’re delivering in our individual and collective work.”

Kirstin Cheers, with United Way, said the overall goal of the three installments is to increase understanding and awareness in the community around the complexity of poverty and “how the multi-faceted layers connect to determine whether a person advances or dormant in this community.”

[pullquote-1]

“Additionally, it is a formal nod to the incredible work of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and his final manuscript that included all these topics,” Cheers said. “It started as a partnership with NCRM to ensure the dialogue and steadfast work of fighting poverty continues on in this community beyond April 4th. It took far longer than a day to get here and will take even longer to overcome.”

The first conversation, which was held in April, centered around equity and understanding the difference between equity and equality. The topic for the last installment, which is scheduled for October 2nd, will be fair wages and quality jobs.

In this final installment, there will also be discussion about how the topics of the previous two conversations — equity and education — determine the outlook for individuals and communities seeking self-sufficiency and economic empowerment.

The discussion on Tuesday begins at 7 p.m. and is free and open to the public.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Facebook

Facebook

Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker  Bruce VanWyngarden

Bruce VanWyngarden