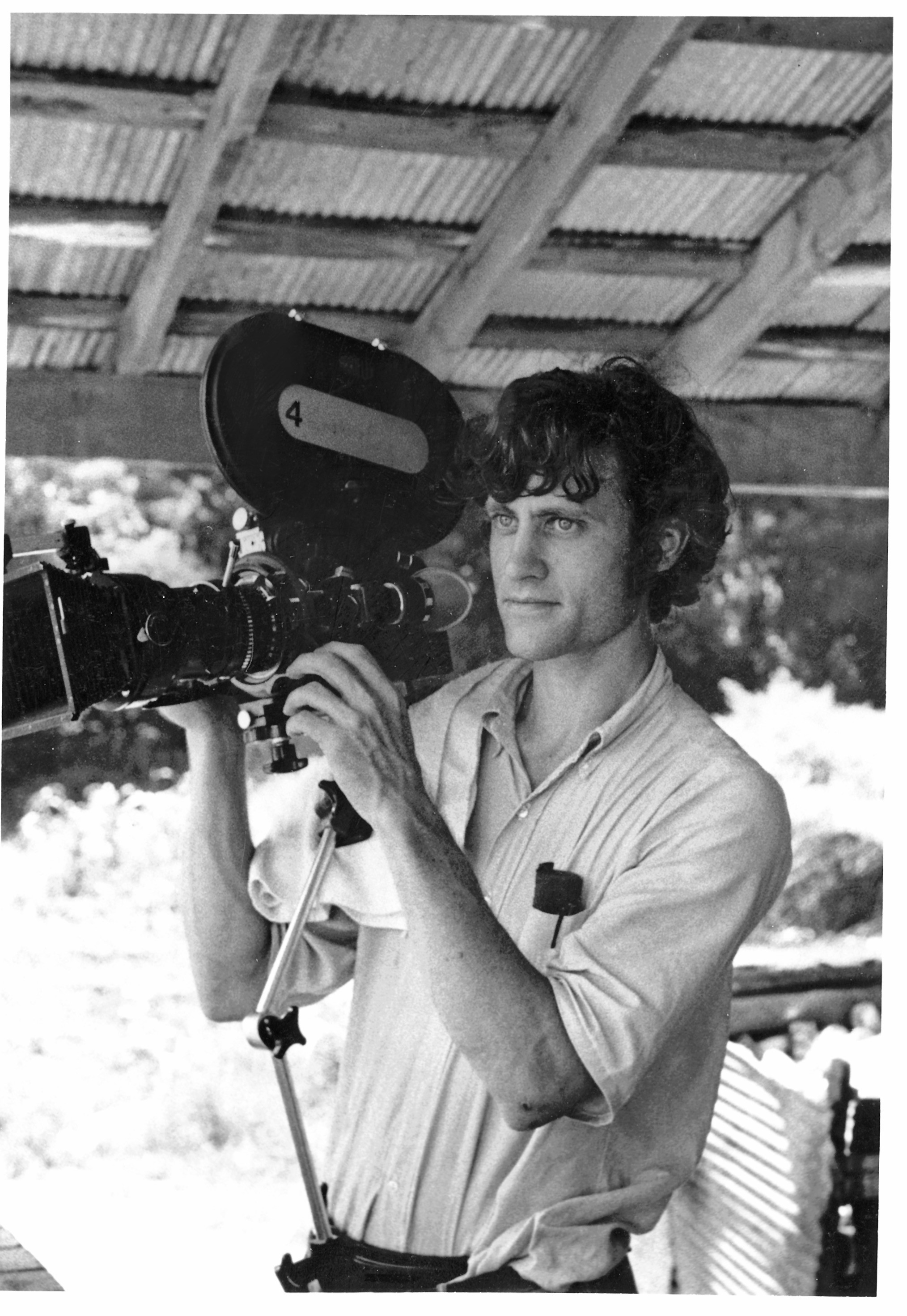

Dr. William Ferris with his camera in Mississippi in the 1970s.

In the early 1970s, William Ferris was a graduate student studying folklore at the University of Pennsylvania. His specialty was studying the rich musical culture of North Mississippi. “I was doing field recordings and photography, and coming back and presenting that. I felt I couldn’t communicate the full power of the church services and juke joints I was working in. Film would be the best way to do that. No one there was willing to help me, at the film school. So I got a little super 8 camera and began to shoot footage and do wild sound on a reel-to-reel recorder. I put together these really basic, early films, which in many ways are the best things I ever did. It’s very visceral, powerful material. I brought those back, and people were just blown away by them.”

Ferris was particularly interested in the proto-blues fife and drum music tradition kept alive in Gravel Springs, Mississippi, by Othar Turner. “I was trying to finish a film on Othar Turner that I had shot, and David Evans had done the sound. Judy Peiser was working at public television in Mississippi, and she interviewed me. I told her about the fife and drum film, and she said she would like to edit it. That led to the creation of the Center for Southern Folklore in 1972, and to a long history of working on films. I would spend my summers in Memphis when I was teaching at Yale. We would work on films and other projects. I made a lot of wonderful friends that I’ve been close to ever since.”

Dr. Ferris, with the help of Peiser and others, acquired progressively better equipment and, over the years, created a series of short documentaries immortalizing the artists and traditions of the Mississippi Delta. His successful academic career would go on to include a stint as the Chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities. Currently, he is a Senior Associate Director Emeritus at the Center for Study of the American South at the University of South Carolina, Chapel Hill. The Center for Southern Folklore, which he and Peiser founded, became a beloved institution in Memphis. “The Center has made a mark, and continues to make a mark with its festivals and exhibits. Judy Peiser has continued it. She’s an anchor for all this work and Memphis, and really a national treasure.”

On Friday, May 17th, Indie Memphis will present “Voices of Mississippi,” a collection of Ferris’ now-classic short documentaries, beginning with “Gravel Springs Fife and Drum.” “Ray Lum: Mule Trader” introduces us to the title character, who Ferris calls “an amazing raconteur.” Ferris recorded the auctioneer’s stories and tall tales in film, and with an accompanying book and soundtrack. “There are two soundtracks. You can hear the wild sound, and his voice. I don’t think that had ever been done before. All of that was published and produced through the Center. I think it was really ahead of its time in terms of media and film.”

“Four Women Artists” documents writer Eudora Welty, quilter Picolia Warner, needleworker Ethel Mohamed and painter Theora Hamblett “Bottle Up and Go” records a Loman, Mississippi, musician demonstrating “one strand on the wall,” a precursor to the slide guitar that makes an instrument out of a house. “It’s one of the earliest instruments that every blues singer learned on as a child, because it was free,” says Ferris. “He also did bottle blowing. Both of those are sounds that have deep roots in Africa and are the roots of the blues.”

Dr. Ferris will bring along some of his Memphis-based collaborators and sign the Grammy-inning box set of his life’s work. He says that for him, this Memphis screening is like a homecoming.“To me, Memphis is the undiscovered bohemian culture,” he says. “You have black and white, rural and folk voices coming out of Arkansas, Mississippi, and Tennessee, meeting this formally educated group of musicians and artists like Sid Selvidge, William Eggleston. Music and photography was a big part of the scene. The photography, because of Eggleston and Tav Falco and Ernest Withers, makes Memphis unique. It just has so many pieces that you don’t find in the French Quarter in New Orleans, where William Faulkner went to write. You have Julian Hohenberg, this very wealthy cotton broker whose heart is in music. He was involved in the music scene for many, many years. It’s the escape valve for people who love the arts. It’s really funky and countercultural. Everything they couldn’t do in these little towns and rural areas, they do in Memphis — and they do it with a passion.”

“Voices of Mississippi” will screen at 6 PM on Friday, May 17 at the Crosstown Theater. RSVP for a free ticket at the Indie Memphis website.