This city is a lot of things. Typical it is not. Memphis has a history strewn with colorful characters. It’s part of our heritage. In the course of writing and researching feature stories for the Flyer, I’ve discovered that colorful characters are still alive and well in the Bluff City, and I’d like to shine the light on a few of my favorites. The subjects of these profiles represent the kind of people who, traditionally, have made Memphis unique: an artist, an entertainer, a preacher, and a protester. They impressed me with their uniqueness of vision, their distinctive styles of self-expression, and their deep commitment to individuality. So for those of you marching to your own beat, we salute you.

Nelson Smith III

Drive up Thomas Street, toward Frayser from downtown into the neighborhood known as New Chicago. Peek down Huron Avenue, and you’ll see a car parked on the south curb beside an old nightclub. Your eyes aren’t deceiving you — that is a red 1984 Pontiac Fiero transforming into a gray Ferrari. Ask one of the fellows sitting outside the club about it, and he’ll explain: “That’s Nelson’s. If he gets an idea, he’s likely to do something about it.”

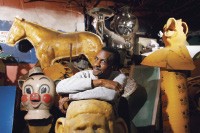

In a city renowned for its artists, Nelson Smith III remains one of Memphis’ best-kept secrets. Smith, 63, creates fanciful and imaginative sculptures and is responsible for some of the city’s iconic commercial art from a bygone era. Samples stand and hang throughout Smith’s studio, formerly Currie’s Club Tropicana, where a young North Memphian named Isaac Hayes had his breakout performance in the early 1960s.

Today the club is part sculpture studio, part machine shop, and part social club. Most days you can find a group of the artist’s friends sitting around a shop table like the Knights of New Chicago, pouring big glasses of brandy, sipping cold beer, frying catfish, or barbecuing chicken. A 12-foot-tall combat soldier lunges at visitors with bayonet drawn just inside the entrance. He glares down through the Phillips-head screws that serve as pupils in his eyes. A yellow cartoon lion and a pig in a paper cap help lighten the mood. And a clue about the artist’s past lurks in the shadows against the back wall. It’s a 10-foot-tall mold of a familiar character unseen in these parts in quite some time — the cheerful, chubby Shoney’s Big Boy, the restaurant’s mascot from the 1950s until his untimely passage to mascot heaven in 1984.

In addition to Big Boy, Smith sculpted the Pizza Inn mascot, designed the logo for Cozy Corner Barbecue, and created art and signage throughout Libertyland, among dozens of completed projects. “That’s what I do — I engineer art,” he says.

Smith took up art as a 10th-grader at Manassas High School, not far from his present studio. He credits a year at the Memphis College of Art — permanently interrupted by Vietnam-era military service — for his mold-making skills. Since then, he’s learned to make do with untraditional materials.

“The stuff that you would throw out — cardboard and scrap wood — I use to shape models for the molds. I never could afford that hundred pounds of clay,” he says, alluding to the title of the Gene McDaniels song about the material God used to fix the world. “I can make any shape out of cardboard.”

His skill and economic use of materials helped Smith foster a mutually beneficial arrangement with the regional Shoney’s franchise. “They kept ordering their statues from California, and it cost a thousand or better bucks just for the shipping, much less the cost of the Big Boy,” Smith says. “I told them I’d make the statue for that.”

Smith used one of the official Big Boy statues to create his mold and then made a fiberglass replica. He stood the statues side by side and invited the Shoney’s owner to choose the original. “You’re hired,” the man told Smith, who produced about 15 of the statues for restaurants in the tri-state region.

The Shoney’s work led to more restaurant projects. Smith outfitted the now defunct Moonraker eatery in Germantown with a pirate ship and theme-decorated Holiday Inn bars like the Red Fox Room and the Coronado Club. Smith explains that technology has since rendered his manual design, engineering, and production techniques obsolete: “I do this by hand, and the computer can cut it right out.”

Today, many of Smith’s signs and sculptures are lost. He doesn’t know what became of his Big Boys, but he stays busy designing sets for school plays and sound studios. And there are his labors of love, including the Fiero-Ferrari. “I’ll get it running again,” Smith says.

Sugarman

Sugarman owns a huge collection of blazers. They’re not new either: double-breasted, broad lapels, and rows of big plastic buttons on both flanks.

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks

Nelson Smith III

He smokes sitting with his legs crossed, the left leg hanging as close to parallel with his right as it gets, arms crossed over his legs with hands hanging limply. He pulls the cigarette toward his lips without lifting the elbow from where it rests.

My wife and I were driving out in the country, and as I made a left onto North Germantown Road from Ellis Road, a figure sitting on the porch of a house set back off that intersection caught the corner of my eye as I accelerated — a shimmering polyester blazer, pointy lapels, gold-rimmed spectacles, white mustache, and ring of white hair, sitting there smoking on a Saturday morning.

“I think that was Sugarman,” I told my wife. But we’d gone by so fast, and she hadn’t met Sugarman and didn’t know about his blazers or his posture.

The next time I saw Sugarman, hanging outside the Boss Lounge on Jackson Avenue, I asked where he stays, and he told me the corner of Germantown and Ellis. “Come by anytime and just ask for Sugarman,” he said. Then he told a group of paper-bag drinkers standing around the parking lot a story. The set-up involved him removing his dentures to orally please a lady friend, an act he refers to — perplexing me completely — as “sucking cock.” This lady enjoyed his technique so much that she stole his false teeth.

We headed inside the Boss Lounge to see Sugarman perform. On stage, that is. Sugarman does not sing particularly well, but as a man in the crowd explains, “He has a way of putting a song over.” He opened with a cover of Tyrone Davis’ “Turning Point,” which recounts the singer’s renouncement of the cheating life. A sample of the lyric in Sugarman’s improvisational style: “No more staying out late, no more narrow escapes, I-I-I-I-I reached the turning point: in my life.”

Sugarman made the song his own. He grafted the introduction of Joe Simon’s “Power of Love” onto the beginning of “Turning Point” before getting into the meat of the song as Davis delivered it. From there, he transitioned to another Davis tune, “Can I Change My Mind.” The band, unaware of Sugarman’s change, continued to play “Turning Point.” They caught on by the second verse, which Sugarman ended by going back into “Turning Point.”

This is how he puts a song over.

Alton R. Williams

The man sprays cologne on his neck, fluffs up the bedsheets, and climbs into bed, waiting expectantly for his wife to join the romantic scene. He calls to her impatiently. After a few minutes, she enters wearing a long, pink terrycloth robe and curlers in her hair.

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks

Sugarman

“What took you so long in the bathroom?” he asks.

“I was getting ready,” she says.

“Ready for what?” he wonders, gesturing at her attire.

“To do the wild thing!” she replies.

That’s one way to get people to come to church.

Tradition can be cumbersome. So believes Apostle Alton R. Williams, who portrayed the man in the above bedroom scene enacted for his church’s congregation a few months back. Williams split from the Baptist church in 1997 and founded the nondenominational World Overcomers.

“That was the beginning of the change from tradition. It became more oriented to the word of God,” he says. “When you’re with a denominational church you stay loyal to that church’s traditions regardless of what the Bible says. When I went to a nondenominational name, the growth of the church really took off.”

The church rolls include more than 10,000 names, though Williams says he sees more like 5,000 people in the pews on Sunday mornings. The church has a staff of about 100. Williams has authored 18 books, which cover topics ranging from Christianity and yoga to a law enforcement prayer guide.

The World Overcomers believe in, among other things: immersion baptism, baptism of the Holy Ghost, speaking in tongues as the initial evidence that accompanies baptism of the Holy Ghost, laying on of hands to heal the sick, women in ministry, rapture, heaven and hell, and that the end-time is fast approaching.

Williams and the Overcomers are known for two things. One is the Statue of Liberation Through Christ, a 72-foot replica of Lady Liberty (about half the height of the original) carrying a cross instead of the torch, with the Ten Commandments tucked into her left arm. It casts its odd shadow from the corner of Winchester Road and Kirby Parkway. (And no, Nelson Smith was not involved in the project.) The other source of Overcomer renown is the series of sermons on marital sex entitled “How To Get the Hell Out of Your House.”

Flyer: How did the infamous sermon on the bed come about?

Alton R. Williams: My wife and I got together in a way that would get people’s attention instead of lecturing them. The reason we did it is because men in their counseling sessions say that they’re not getting what they want or getting it frequently enough. Many women have religious mindsets about sex. They come in thinking it’s a duty. A lot of them have not come into it thinking about pleasure for themselves because of the way mama or religion has taught them — that sex is your duty, and it’s for the man. We want women to be free to enjoy sex. The Bible, in Genesis 18:12, says that Sarah all the way back in the Old Testament called sex pleasure. She didn’t see it as a duty or having a baby. Our women need to know that they can enjoy it. The key book in the Bible is the Song of Solomon. I think people would be shocked if they read that and saw for themselves what God permitted and what they can do in the bedroom.

Example?

The most important thing in there is how the wife, in [Song of Solomon], is the one leading the sexual escapades. You don’t find that a lot in women, particularly Christian women. The Bible talks about tongue kissing, that’s in there. There’s a part of Scripture where a woman talks during the sexual escapade, telling her partner what she wanted. The Bible talks about how the man looks at her physical body — it brings out the breast, her hips, her legs, her navel, all of that. Men are stimulated by what they see. Women need to know that men aren’t crazy because of that. It’s allowed in Scripture. In first Corinthians 7:5, the Lord said you cannot go and pray unless it’s with the consent of your mate. That means if your mate wants to have sex before you start praying, you gotta put prayer aside and go take care of the need. Now that’s how high a priority God placed on sexuality.

How did the Statue of Liberation Through Christ get here?

Driving down I-40 to Nashville, I passed by Bellevue Baptist Church’s crosses, and I saw those crosses as a witness to the world. We’re sitting on the best corner in Memphis [Winchester Road and Kirby Parkway], and I asked myself what I could do that wouldn’t duplicate what Bellevue had done. One night, watching TV, if you notice when Letterman comes on there’s a big picture of the Statue of Liberty that rolls by. For a flash second I saw a cross in the Statue of Liberty’s hand. The thing that finally pushed me to do it was the Buddha statue on Mendenhall. If you go look out in that area at Winchester and Goodlett, behind that Wendy’s is a big field, and there are several Hindu statues that have been put up. People actually go and worship those things. I see these things that honor other gods, and I wanted to do something that would give God glory and minister a message about America not leaving its Christian heritage.

The concept of the end-time is one of your church’s core beliefs. Are we getting close?

Oh God, yes. There are so many signs: the frequency of the storms. In one week, you had several tornadoes, you had an earthquake in China, fires, and floods all at one time. The Bible says that all these things will begin to happen with greater frequency. The people living on earth are moving more toward sin and iniquity, and the earth is reacting to that. The earth begins to groan, the Bible says, because of all the evil in the world. We are rapidly moving toward end-time.

Can you provide us an estimate?

God doesn’t give us that.

Jackie Smith

Seven thousand four hundred six days and counting. The demolition men and the wrecking balls came to level the Lorraine Motel, and Jackie Smith refused to leave. She locked the door to Room 303 and practically starved as the snow piled outside. Finally, they kicked the door in and carried her away. Judges served injunctions and issued restraining orders to keep her away from the property. So she pitched a tent across the street on the corner of Mulberry Street and Butler Avenue, and there she stayed. Street people beat on her and stole from her. Rain poured and icicles dangled from a chain-link fence. And she stayed.

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks

Apostle Alton R. Williams

Smith’s vigil at the site of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination continues as it has for more than 20 years. And so do the challenges. As I approached Smith’s encampment on a recent sunny afternoon, a man turned to me and said something nasty about her. He stopped and threatened her, then he walked on, and I asked her what his problem was. She said that he should be working instead of begging for money to spend on dope. “I’m a lady,” she began, “and I have a good man who takes care of me. I don’t have to work.”

She’s heard all of the amateur psychology and remains unmoved. The soft-spoken protester doesn’t bother anyone; visitors have to choose to visit her and talk. She’s trimly built and cleanly dressed, her head wrapped in a black shroud as a mourner’s might be. She sits behind a desk scattered with a sun-bleached copy of Flyer columnist John Branston’s Rowdy Memphis, a yellowed edition of a Flyer dating from 2001, a photograph of King lying in state, copies of King sermons and self-produced fact sheets in plastic sleeves, and a copy of William F. Pepper’s Orders To Kill: The Truth Behind the Murder of Martin Luther King Jr. with the cover torn off. Inside a desk drawer are an assortment of pens and markers, thumbtacks for the banners she hangs, and lip balm.

She sings — sometimes opera, sometimes pop — for up to an hour each morning. Sometimes hecklers disrupt the vocal workout. She reads aloud to visitors from King’s sermons, offering “he’s so funny” as an aside to particularly clever examples of King’s rhetoric.

Smith says there’s no way to calculate the number of people who’ve elected to stop by over the years to hear her detail the irony of making this area nice for the bourgeoisie, despite the fact that King died for the poor. Now they have parties around the place she holds sacred, she says, and people drink beer under the path of the bullet that killed King. “I’m sure Dr. King enjoyed a beer in his life, but it’s not decent.”

She doesn’t know how many more thousand days she has, but just as the odd beat of our unique city goes on, so will her one-lady protest: “I don’t have plans to move from here until the good Lord calls me home. But I’ll let you know when it’s time for the grand finale.”