“Before I left New York, I had had tryouts for the band and that’s where I got all these Memphis musicians … I wonder what they were doing down there, when all them guys came through that one school?” — Miles Davis, Miles: The Autobiography

Sometime in the late 1940s, Herman Green, a teenaged saxophone player, found himself playing a show in Kansas City, and wound up speaking with another reed man. “How long you gonna be in Kansas City?” the older musician asked.

“Well, we just up here for the weekend. We gotta go back to Memphis,” Green replied.

“Oh, you from Memphis?” said the other player. “That’s why you’re playing the way you’re playing. ‘Cause you had some good teachers down there.” Green had never heard of the older fellow, but he would remember his name all his life: Charlie Parker.

Herman Green passed away recently, at 90, “at home, surrounded by family, listening to Coltrane,” according to a close friend. He was a revered figure in the local music scene — just as he was taught by “some good teachers,” he taught and mentored many here. And his life, crossing paths with the likes of Sonny Stitt, Lionel Hampton, and John Coltrane, was emblematic of Memphis’ place in the history of jazz, a place honored and treasured by a few, yet unknown to most. Tourists think of Memphis as a blues town. But these days, assuming the onslaught of a mismanaged pandemic is brought to heel soon, that may be changing.

Jamie Harmon

Jamie Harmon

Kirk Whalum

For starters, the blues/jazz distinction doesn’t mean all that much to many musicians. Recently, renowned jazz saxophonist Kirk Whalum, a Memphis native, told me about the transcendent playing of organist Andre Stockard, whom he happened to see at B.B. King’s Blues Club. I asked him if what he heard that night was jazz. “As far as I was concerned, yes,” said Whalum, “but it was in the context of the blues. It’s all kind of mixed up, right?”

And that may just be the key to the unique qualities of Memphis players. Long before Sun or Stax, “the Memphis Sound” was a topic among music aficionados, beginning in the late 1920s, when Jimmie Lunceford, the city’s first public high school band director, put Memphis music on the map by transforming the Manassas High School band into “the Chickasaw Syncopators.” Eventually becoming the Jimmie Lunceford Orchestra, they were a crack ensemble that ultimately toured the country and cut scores of records. That may have marked the first time that the distinctive, bluesy soulfulness of the city’s players caught the public ear. But it wasn’t the last.

As the Miles Davis quote above suggests, Memphis players have long been sought after. The most obvious examples include George Coleman, Harold Mabern, and Frank Strozier, who played with Miles personally, but also include such 20th century luminaries as Phineas and Calvin Newborn, Booker Little, Hank Crawford, and Charles Lloyd. Later examples include pianists James Williams, Mulgrew Miller, and Donald Brown, all graduates of what was then Memphis State University, all of whom played with Art Blakey’s famed Jazz Messengers. And the list goes on, to this day (thoroughly explored in the locally produced podcast and WYXR radio show, Riffin’ on Jazz, which dedicates two episodes to the Memphis-Manhattan connection).

Jamie Harmon

Jamie Harmon

Joe Restivo

Saturday Night and Sunday Morning

A common influence shared by this multi-generational roster is the two-headed beast of Saturday night/Sunday morning, aka, Beale Street and the church. As Stephen Lee, an accomplished jazz pianist who founded the Memphis Jazz Workshop, notes, the two styles rely on their heavy use of two chords in particular, most commonly associated with the “Amen” that ends nearly every hymn. “We get it from playing the blues on Beale street, from playing those same ‘one’ and ‘four’ chords. And it might not be the blues, but that one and four is in all gospel, the old gospel. There’s something in that one-chord to the four-chord change that stands out and has so much soul in it. Memphis is right there, between that one and four chord! It has a lot of meaning. You get it in blues and you get it in church.”

Joe Restivo, guitarist with the City Champs, the Love Light Orchestra, and his own quartet, tends to agree, adding that young players learn more than just notes from the blues/gospel milieu. “The really developmental gigs are in the R&B scene, and that’s gonna be on Beale Street. Preston Shannon [a Beale Street fixture] had so many great musicians run through his band and learn how to play a gig. Some of those people became jazz musicians. Like Anthony Crawford, Hank Crawford’s grandson, who went to L.A. and became a big time fusion jazz bassist. He went through that Preston Shannon school of learning how to play gigs and learning your instrument.

“To me, that’s the same thing as Herman Green and George Coleman and Charles Lloyd going through the B.B. King and Bobby Bland bands. They’re not necessarily playing jazz, but they’re learning their horn, they’re playing a gig, they’re learning the language and the repertoire, they’re learning how to act. You gotta show up on time, dress in a certain way, be professional. Learn the songs. Learn how to get house. Learn how to entertain.”

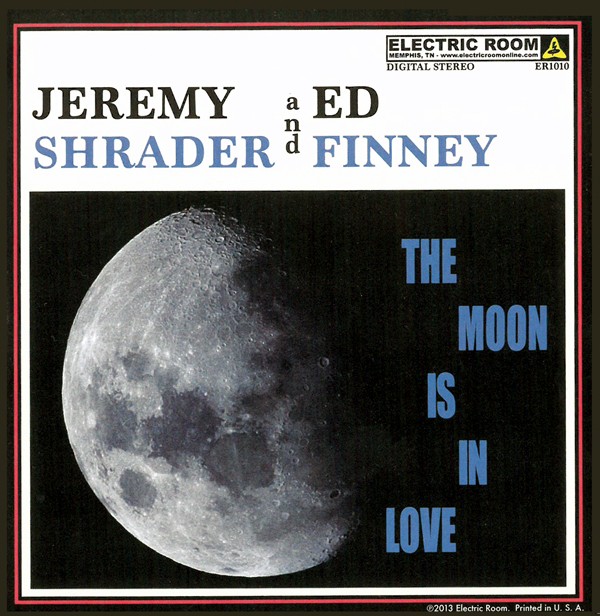

Courtesy Ed Finney

Courtesy Ed Finney

Ed Finney

Restivo is quick to point out that these same musicians are technical masters of their instruments as well. Memphis players, he notes, “were sought after and they were known for how soulful they were, and how hard they swung, and how funky they were. But also how virtuosic they were. That’s something people don’t realize. A lot of these musicians are also widely known for their technical acumen, not just their feel. Phineas Newborn was a virtuoso. Booker Little was a virtuoso. MonoNeon is a virtuoso.”

How It Began

The history goes back to the 1920s, as University of Memphis music instructor Sam Shoup notes. “If you’ve ever seen footage of the Jimmie Lunceford Orchestra, it’s incredible. It’s like James Brown times 10! When I first started one of the big bands at U of M, we did a tribute to Jimmie Lunceford and played three or four of his songs, and they were hard as hell! We had to work and work and work on them.”

Shoup sees the benefits of the city’s strong music education game every day at the U of M. “We’re getting some really good players. A lot of that has to do with the school system. Schools like Central, Overton, Briarcrest, and White Station have excellent jazz programs. The Stax Music Academy and the Memphis Music Initiative are doing some great things. They’re involved in all types of music, and they’ve been big supporters of jazz. Another big help is the Memphis Jazz Workshop that Stephen Lee is doing. There are middle school kids there that can really play, and now, since we started doing that in 2017, I’m starting to see high school kids who’ve done that coming to college, and they’ve got a leg up on everybody else.”

The University of Memphis has produced some downright legends. The Jazz Studies program there, founded by Tom Ferguson in the 1960s, has long been a beacon for those aspiring to professional jazz chops. Sam Shoup was inspired by the U of M student bands when he was in high school. A short while later, he was accepted there himself. “The best jazz scene I was ever around was in the 1970s, and the center of that was James Williams. At one time, we had James Williams playing in the A band, Mulgrew Miller playing in the B band, and Donald Brown playing in the C band. We all went to school together. These guys were just walking around in the hall every day. Mulgrew and Donald were in my theory class.”

Donald Brown went on to return the favor to posterity, ultimately becoming an instructor at the University of Tennessee-Knoxville, where one of his students was Stephen Lee. More recently, he taught and mentored the up-and-coming Maguire Twins, a drum and bass duo, and appeared on their debut album. Though neither plays piano, Lee points out that some of the wisdom gained from a veteran like Brown transcends technical instruction. “Some of my best lessons with Donald Brown,” he says, “were just conversations. Talking about other jazz musicians and their approach to music.”

James Williams exemplified another form of paying it forward. According to the hosts of Riffin’ on Jazz, he was “a conduit” for other Memphians seeking their fortune in New York. “They’d go up there, they’d look for James, and James would help them find gigs, help them get recordings. James was like the guru of New York.”

And he paid it forward when back home for the holidays as well, right around this, the most wonderful time of the year. “James would have that jam session at the North End around Christmas every year. So I’d go down and talk to him and Mulgrew Miller and Tony Reedus,” says Lee.

Jamie Harmon

Jamie Harmon

Daru Jones and MonoNeon of Project Logic

The Mentorship Tradition

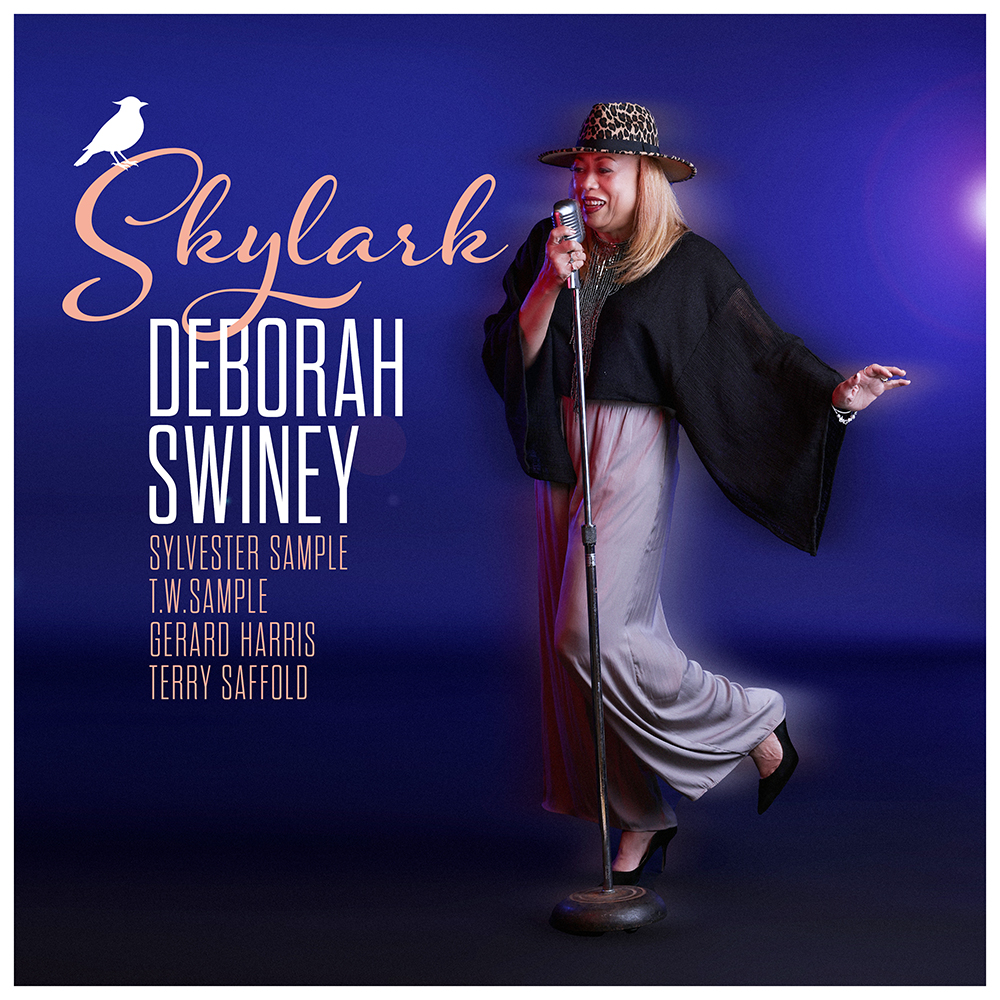

Guitarist Ed Finney, aka Jupiter Skyfish, who until recently could be seen almost every week accompanying singer Deborah Swiney, graduated from R&B to jazz thanks largely to the mentors he met along the way. Introduced to music by his father, who led the Harmonica Hotshots, Finney began performing with an R&B band at the Flamingo Club in 1964. “We played about six months and they became the Bar-Kays, without me,” he recalls. “And then I played at a club where the band leader, my first real mentor in jazz, was Floyd Newman. He was a great baritone sax player, and he was also writing horn charts at Stax; that was probably ’65 to ’67. So I got exposed to jazz. We were a rhythm and blues group, but we had a jazz bass player. And Isaac Hayes would come in and play piano with us.”

True to the process Restivo and Lee describe, simpler, groovier music was Finney’s stepping stone to jazz, as he plied his trade in clubs on Beale and throughout the region. “I played more in the rhythm and blues scene,” recalls Finney. “At that point, guitars were really rhythm instruments. And I played a lot. We were playing five, six nights a week, nine to three every night. And if I traveled with a band, I had to play as an ‘albino.’ It was illegal for me to play in a white club with a Black band. The thing about it, all those clubs had red lights in them, they were dark, and full of cigarette smoke. And I had kind of an afro. At the Tiki Club, the owner found out I wasn’t Black and said, ‘Well, you’ve been faking it for a year. Just come in the back door.'”

Gifted with both talent and indefatigable curiosity, he soon fell in with Herman Green. “He’d been in New York,” says Finney. “He sounded a lot like ‘Trane when he first came back, into that ‘sheets of sound’ kind of thing. He was a great, great tenor player. Obviously one of the best that’s ever come from this city. He was a mentor to me. I played with him for three or four years, off and on. I traveled a lot. I went to New York and played with some great musicians there. Jack DeJohnette, Bob Moses, and Insect Trust.”

The fact that Finney is still playing and composing to this day (still working with pioneers like Bob Moses) is a testament to the through line of inspiration and instruction that carries the Memphis jazz legacy forward. Herman Green, educated first at church, then at Booker T. Washington High School, then mentored by Rufus Thomas on Beale Street, goes on to travel the world, playing with some of the greatest innovators in jazz. Inspired by Coltrane’s radical approach, the cascading cacophony of “sheets of sound,” he returns home and mentors Ed Finney, among many others, who in turn goes on to make a name in the world of free jazz, and continues to do so, even as his mentor passes on.

Courtesy Stephen Lee

Courtesy Stephen Lee

Stephen Lee

The Memphis Sound

Thus history reveals the ever-evolving forms of jazz, in which a thread of “the Memphis Sound” can still be discerned. Restivo, whose Where’s Joe? album proffers an edgy take on classic jazz and jump blues sounds of the ’50s and ’60s (even as the City Champs mine funkier, boogaloo-rooted territory), tends to take the long view on all the avenues open to today’s jazz pioneers, once they’re grounded in the Memphis experience. “You’ll see some players take it in a certain direction, a more modern jazz sound, like Booker Little or George Coleman,” Restivo says. “Or maybe it’s someone who wants to pursue a smoother contemporary jazz sound, like Kirk Whalum. Or maybe they want to be more R&B or hip-hop. It all comes from that same place. And the community’s very supportive. Everybody knows everybody. I’m seeing a whole new, young crop of songwriters and players and singers and instrumentalists. They’re all very impressive.

“I think it’s individual. Some people tend to look backwards and explore their voice through older aesthetics, and some people are more futuristic. Like MonoNeon. But even he has that classic approach in there. Once you have that foundational stuff, you can go anywhere you want with it. Do you want to focus on Charlie Parker and Bud Powell’s music, or focus on Herbie Hancock, or maybe take it in the direction that guys like Robert Glasper are going now, synthesizing hip-hop and jazz. That guy’s music is amazing, drawing from both Duke Ellington and J Dilla. He was at the New School when I was there. He’s a huge titan in the current jazz world. Whatever you want to do with it, if you’ve got these foundational elements, you can do that.”

IMAKEMADBEATS, hip-hop producer and founder of the Unapologetic collective, is an unlikely champion of this inclusive, pioneering spirit of the music, and, along with the youth making such strides under Stephen Lee’s guidance, may be paving the way for a Memphis jazz Renaissance. “Memphis is very blues and soul oriented,” he says, “but if you’re willing to dive into the underground, it’s definitely there. Even in stuff that’s more electronic, that jazz influence is definitely there and appreciated. I’ve found some really great jazz musicians who I work with. I like to defy and disrupt. To me, that’s the heart of jazz. That’s why hip-hop samples jazz; there was no ‘classical music era’ in hip-hop. The most sampled music in hip-hop is jazz, because jazz disrupts.”

It’s that unpredictable quality that draws even hip-hop artists to jazz of all eras, but also makes it a tough sell in tourist-dominated sectors like Beale Street. Yet all the artists I spoke with long for a space they can call their own, once live performances become possible again, a place where the spirit of adventure meets a respect for living history: a bona fide jazz club.

“It’s been talked about for years, ever since I was a teenager,” says Restivo. “Joyce Cobb had her club briefly. I remember seeing Herb Ellis there, and it was a very formative experience for me. I wish we had a club like Rudy’s in Nashville. Or Snug Harbor in New Orleans. A jazz room, where jazz is what you’re coming for. Kansas City has a couple; that town has really fostered and maintained its history. An art space built on the nonprofit model, like the Green Room at Crosstown, is important. But it would be awesome to have a real jazz club.”

It’s hard to believe that Finney launched his career, so representative of all that is untethered and pioneering in jazz, on Beale Street. But his memories of that era may yet point us to the future. “There was probably jazz in Memphis before there was jazz in New York,” he reflects. “Beale Street was not a blues street. It was a street for Black elites. People that were movers and shakers in the Black community. Like writers, journalists, owners of shops, whatever. When you went to Beale Street, you’d walk in the club and you’d hear something more like Duke Ellington’s band. Everyone was all dressed up. Yes, blues is important, and I love blues. It’s the mother of it all. But I am a little sad that Beale Street is only a blues street now, because that’s not what it was.”

Having seen the next generation firsthand, Stephen Lee is hopeful. “The youth will have to bring the scene back. There are a lot of kids in Memphis, really good musicians, all under 30, with no gigs. And this is even before COVID. They’re practicing, rehearsing, and a couple are teaching. There’s a scene here, just waiting to be cultivated.”

Jamie Harmon

Jamie Harmon  Jamie Harmon

Jamie Harmon  Courtesy Ed Finney

Courtesy Ed Finney  Jamie Harmon

Jamie Harmon  Courtesy Stephen Lee

Courtesy Stephen Lee